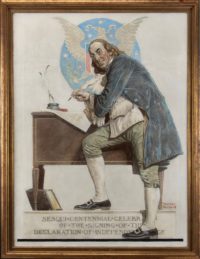

A rare painting of Benjamin Franklin striking a saucy pose as he signs the Declaration of Independence will be sold to the highest bidder at The Carrie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds Personal Property Auction to be held in Los Angeles on October 7th-9th. For the past seven years until Ms. Reynold’s recent death, the painting was on loan to the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts which must be disconsolate by the loss of so important and unique a piece.

A rare painting of Benjamin Franklin striking a saucy pose as he signs the Declaration of Independence will be sold to the highest bidder at The Carrie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds Personal Property Auction to be held in Los Angeles on October 7th-9th. For the past seven years until Ms. Reynold’s recent death, the painting was on loan to the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts which must be disconsolate by the loss of so important and unique a piece.

The painting is accomplished in oil on 37 x 28 in. canvas, capturing a full-length portrait of Benjamin Franklin with a quill pen in hand, prepared to sign The Declaration of Independence and leaning on a Federal-style desk with the Seal of the United States behind him. The platform base reads, “Sesqui * Centennial * Celebration * of * the * Signing * of * the Declaration * of * Independence”. This incredibly historic Rockwell work has been exhibited in twelve museums around the United States since 1972 and has been published in several books.

Rockwell painted the work for the cover of the May 29, 1926, edition of the Saturday Evening Post commemorating the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The Post commissioned the subject and chose Benjamin Franklin for a specific reason: Franklin was the publisher of the influential Pennsylvania Gazette, the Philadelphia newspaper that the Saturday Evening Post claims as its historical ancestor, even though the Post didn’t exist until 1821 and the Gazette ceased publication in 1800.

The Post‘s reverence for Franklin continued to be expressed in its covers for decades. Between 1943 and 1961, every January the cover would feature a portrait of Benjamin Franklin (usually rather dry ones with a sadly unsaucy stone bust in the foreground) and a quote from his writings. Even today the revived magazine runs a “find Benjamin Franklin’s key” contest, named after his famed kite experiment first published anonymously in the Pennsylvania Gazette of October 19, 1752.

The pre-sale estimate for the oil-on-canvas original capturing the history of one of the United States’ most brilliant innovators, statesmen and printers and a magazine whose slice of Americana covers by Norman Rockwell have become iconic is $2,000,000 – $3,000,000. This is the first time the painting has been gone up for public auction, so the sky is probably the limit, pricewise.

Some of the proceeds from the auction will go to Debbie Reynolds’s most beloved charity The Thalians and The Jed Foundation, an anti-suicide organization chosen by Carrie Fisher’s daughter Billie Lourd.