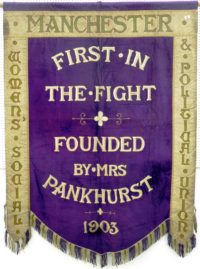

The People’s History Museum (PHM) has acquired a very rare suffragette banner that was made in Manchester in the early 1900s and will now return to its native city again more than 80 years of exile in Leeds. Created by premiere Manchester banner maker Thomas Brown & Sons, the banner celebrates the founding of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) by Emmeline Pankhurst, one of the fiercest and most committed suffragette leaders, in her home at 62 Nelson Street, Manchester, in 1903. The date of its manufacture is not known, but the banner glows with the colors of the WSPU campaign: green signifying reform, white purity and purple dignity. The green, white and purple weren’t adopted as the WSPU’s official colors until 1908.

The People’s History Museum (PHM) has acquired a very rare suffragette banner that was made in Manchester in the early 1900s and will now return to its native city again more than 80 years of exile in Leeds. Created by premiere Manchester banner maker Thomas Brown & Sons, the banner celebrates the founding of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) by Emmeline Pankhurst, one of the fiercest and most committed suffragette leaders, in her home at 62 Nelson Street, Manchester, in 1903. The date of its manufacture is not known, but the banner glows with the colors of the WSPU campaign: green signifying reform, white purity and purple dignity. The green, white and purple weren’t adopted as the WSPU’s official colors until 1908.

The WSPU marched and assembled under their banners, but unlike many of their sisthren in the cause, they took an explicitly militant stance. Sick of failed attempts to extend the franchise by ostensibly allied politicians, the WSPU took as their motto “deeds not words” and hit the streets. They tied themselves to railings, blew up mailboxes, went on hunger strikes when they were arrested and refused to eat even under threat of force-feeding. They made a very effective nuisance of themselves until World War I broke out in 1914 and the WSPU suspended all its activities.

The WSPU marched and assembled under their banners, but unlike many of their sisthren in the cause, they took an explicitly militant stance. Sick of failed attempts to extend the franchise by ostensibly allied politicians, the WSPU took as their motto “deeds not words” and hit the streets. They tied themselves to railings, blew up mailboxes, went on hunger strikes when they were arrested and refused to eat even under threat of force-feeding. They made a very effective nuisance of themselves until World War I broke out in 1914 and the WSPU suspended all its activities.

As far as researchers have been able to determine, the banner was taken to Leeds in the 1930s by Edna White. It was sold to the charity shop after her death and this rare textile treasure remained in the shop, unrecognized and unappreciated, for 10 years. The charity shop put the banner up for auction on June 20th of this year where it was bought by a private collector.

As far as researchers have been able to determine, the banner was taken to Leeds in the 1930s by Edna White. It was sold to the charity shop after her death and this rare textile treasure remained in the shop, unrecognized and unappreciated, for 10 years. The charity shop put the banner up for auction on June 20th of this year where it was bought by a private collector.

The People’s History Museum, which has the largest collection of trade union and political banners in the world and a top notch textile conservation studio to ensure their long-term health, wasted no time. They reached out to the collector and agreed on a buying price for the banner. They then raised most of the money in grants from the Arts Council England/V&A Purchase Grant Fund and the Heritage Lottery Fund. With £5,000 still to go, the museum turned to crowdfunding. The Bring Manchester’s Suffragette Banner Home campaign was an almost instant success, meeting the original target in a week.

The People’s History Museum, which has the largest collection of trade union and political banners in the world and a top notch textile conservation studio to ensure their long-term health, wasted no time. They reached out to the collector and agreed on a buying price for the banner. They then raised most of the money in grants from the Arts Council England/V&A Purchase Grant Fund and the Heritage Lottery Fund. With £5,000 still to go, the museum turned to crowdfunding. The Bring Manchester’s Suffragette Banner Home campaign was an almost instant success, meeting the original target in a week.

The PHM has added another £2,500 as a stretch goal to help fund interpretation of the newly acquired banner for its display in a 2018 exhibition celebrating the centenary of the passage of the Representation of the People Act which granted suffrage to all men 21 and older and women 30 and older. (Women 21 years of age and above were not enfranchised until 1928, a matter of a few weeks after Emmeline Pankhurst’s death.) The rest of the stretch money would go to getting the rest of the museum’s suffrage collections in top shape and creating learning resources and events associated with the exhibition. They’ve only raised a few hundred pounds of the stretch goal with just over two weeks to go.

The PHM has added another £2,500 as a stretch goal to help fund interpretation of the newly acquired banner for its display in a 2018 exhibition celebrating the centenary of the passage of the Representation of the People Act which granted suffrage to all men 21 and older and women 30 and older. (Women 21 years of age and above were not enfranchised until 1928, a matter of a few weeks after Emmeline Pankhurst’s death.) The rest of the stretch money would go to getting the rest of the museum’s suffrage collections in top shape and creating learning resources and events associated with the exhibition. They’ve only raised a few hundred pounds of the stretch goal with just over two weeks to go.

Helen Antrobus, Programme & Events Officer at PHM, says…

“This is a truly spectacular piece, beautifully crafted and powerfully representative of its time. It is also an important part of the nation’s social history and we hope to find out more about Edna White and her suffragette story as part of this project’s research. The banner’s life began in Manchester and we’d like to continue its life by sharing its story with our visitors who travel across the region, nation and world to join us on a march through time that narrates Britain’s struggle for democracy.”

The campaign will ensure that the banner not only becomes a part of the People’s History Museum collection, but that plans are in place for its continued care and conservation by the museum’s specialist team.