The Penn Museum is deploying one of nature’s highest precision weapons, the canine olfactory sense, in the fight against artifact looting. The museum, the Penn Vet Working Dog Center and the nonprofit Red Arch Cultural Heritage Law and Policy Research are working together on a project that will train dogs to detect and protect smuggled artifacts.

No longer a matter of local desperadoes trying to make a quick buck, artifact smuggling is big business now, generating an estimated four to six billion a year in blood-drenched profits for the criminal and terrorist organizations.

“[K-9 Artifact Finders is] an innovative way to disrupt the market in illicit antiquities, and that’s really what needs to happen to slow down the pace of looting and theft in conflict zones,” consulting scholar for the Penn Museum and 2000 Penn doctoral graduate Michael Danti said. “Currently, art crime, that means fine arts, antiques, antiquities, is usually ranked as the fourth or fifth largest grossing dollar criminal activity in the world on an annual basis.”

Danti said terrorist organizations often use stolen cultural artifacts to fund their operations, deliberately destroying them and using them for propaganda and “click-bait.” He added that high-profile groups like the Islamic State have continuously done this, setting a precedent for other similar organizations to employ the same techniques.

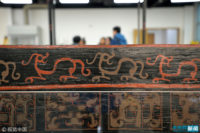

The K-9 Artifact Finders program is still in the initial setup phase at this point. The plan is divided into three parts, much like Caesar did to Gaul. To narrow down the almost impossibly broad range of smells associated with cultural heritage objects, trainers will focus on the Fertile Crescent which has been devastated by war, instability and increasingly professional organized criminals that treat the area’s immense cultural patrimony like their personal piggy bank. Penn Museum’s world-class collection of Mesopotamian artifacts will be invaluable in this pursuit.

Four dogs from the Working Dog Center’s, carefully selected for their noses and temperament, will learn to distinguish between up to three types of newly excavated objects. Once the dogs have completed the scent imprinting and recognize what they’re supposed to look for, the trainers will teach them to distinguish between different subsets of odor.

[Penn Vet professor Cynthia] Otto said there is a special procedure to introduce the smell of artifacts to dogs without compromising the artifacts.

“Our main training approach will be to use cotton balls and let the artifacts and cotton sit together in a closed non-permeable bag. That way the odor from the artifacts is absorbed by the cotton and we don’t have to risk damage to the artifacts,” Otto said. “We will also train the dogs to ignore the odor of the plain cotton and other things that might be similar but not the actual artifact.”

The second phase will be on-the-ground testing and the third a demonstration program that would give customs officers the tools to train their own K-9 units to find smuggled artifacts. Phases II and III don’t have all the funding they need yet. To make a tax deductible donation to help get the program from theory to practice, click here.

There are a lot of unknowns about this ground-breaking idea, like whether it’s even possible for dogs to distinguish between artifacts and things that smell like them due to a shared environment or what have you. I bet it is. One should never underestimate the power of the canine nose, and the anti-looter squad wouldn’t be the first dogs used in aid of archaeologists. Migaloo, a very good girl from Brisbane, Australia, was trained to detect human remains of archaeological age. Cadaver dogs have been around a long time, but Migaloo was the first to have the nose and the training to detect ossified remains, not decaying flesh. She found 600-year-old skeletal remains buried eight feet underground during one her tests.