The Library of Congress, ever on the ball, has completed the digitization of abolitionist Emily Howland’s carte-de-visite album. The 48 pictures date to the 1860s and include the earliest extant portrait of Harriet Tubman. The Library of Congress and the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture pooled their resources and bought the album at auction a year ago for $162,500 (including fees).

The Library of Congress, ever on the ball, has completed the digitization of abolitionist Emily Howland’s carte-de-visite album. The 48 pictures date to the 1860s and include the earliest extant portrait of Harriet Tubman. The Library of Congress and the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture pooled their resources and bought the album at auction a year ago for $162,500 (including fees).

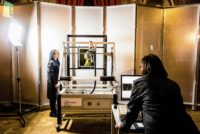

Since then, the album has been thoroughly conserved by LoC experts. Its damaged cover was reattached, the leather was conditioned and treated and each picture was cleaned. Researchers have scoured records and identified all but three of the sitters. Digitization specialists from the Library and the Smithsonian, both of which have been at the forefont of efforts to digitize their collections, have scanned the portraits in high resolution and uploaded them to the LoC website.

There are a number of prominent abolitionists, both people she knew personally (Colonel Charles W. Folsom, Charles Sumner) and celebrities (Charles Dickens, Princess Dagmar, Empress of Russia). Harriet Tubman’s photograph depicts her as a stylish woman in her 40s just after the Civil War, not with the care-worn visage of her older years that is usually associated with her.

Also in the Howland album is the only known photograph of John Willis Menard, the first African American man elected to the United States House of Representatives. He was never seated because his opponent contested the election results even though Menard had won a clear majority of the vote and the House denied him his seat based solely on the color of his skin. Future president James Garfield, then a Representative from Ohio’s 19th district, and a strident abolitionist who was pro-Reconstruction and pro-universal male suffrage, stated so outright when he said “it was too early to admit a Person of Color to the U.S. Congress.” Menard delivered a speech advocating he be seated, making him the first African American to address Congress. Even though his opponent Caleb Hunt did not address the chamber, when it came time for the House to vote on which candidate to seat, neither one of them got close to the necessary majority.

Also in the Howland album is the only known photograph of John Willis Menard, the first African American man elected to the United States House of Representatives. He was never seated because his opponent contested the election results even though Menard had won a clear majority of the vote and the House denied him his seat based solely on the color of his skin. Future president James Garfield, then a Representative from Ohio’s 19th district, and a strident abolitionist who was pro-Reconstruction and pro-universal male suffrage, stated so outright when he said “it was too early to admit a Person of Color to the U.S. Congress.” Menard delivered a speech advocating he be seated, making him the first African American to address Congress. Even though his opponent Caleb Hunt did not address the chamber, when it came time for the House to vote on which candidate to seat, neither one of them got close to the necessary majority.

Not all of Emily Howland’s friends and colleagues in the album were pioneers, heroes and icons. Poor Susie Bruce was one of her protéges, a student who lived with her for the school year and whom she arranged to send to Oberlin College to continue her education. Howland insisted that her mentees work to pay for their room and board, however, so that they wouldn’t be distracted by boys and pretty clothes, and Susan was sickly — she suffered from a chronic “side ache” — and neither a great student nor capable of accomplishing all the tasks set to her in her off-hours. Also she liked pretty clothes.

Not all of Emily Howland’s friends and colleagues in the album were pioneers, heroes and icons. Poor Susie Bruce was one of her protéges, a student who lived with her for the school year and whom she arranged to send to Oberlin College to continue her education. Howland insisted that her mentees work to pay for their room and board, however, so that they wouldn’t be distracted by boys and pretty clothes, and Susan was sickly — she suffered from a chronic “side ache” — and neither a great student nor capable of accomplishing all the tasks set to her in her off-hours. Also she liked pretty clothes.

When Susie got sicker and Emily received reports from her host that she wasn’t working at all hard, Howland had her withdraw from college before her freshman year was over. She returned to Washington, now very seriously ill, and four months later she was dead, felled by an undiagnosed “disease in her bowels” that was had been the source of her mysterious side ache. Emily wrote this rather faint praise about Susie after her death: “So all is over, hopes, fears and plans, the grave ends all. I think she would not have disappointed me could she have lived.”

She was doubtless happier with another of her protéges pictured in the album, Sidney Taliaferro. She was the daughter of freedman Benjamin Taliaferro whose extended family Emily had settled on a large parcel of land she bought in Northumberland County, Virginia. This was her way of keeping the broken “40 acres and a mule” promises. If the government wouldn’t acquire land for freedmen, then she would. She had a school built there, the Howland Chapel School, to educate their children. (The building is still standing today largely unaltered and on the National Register of Historic Places.) Sidney did so well that Emily brought her up north to attend a secondary school run by a relative of hers in New York state and then onto college. She became a school teacher too, and after a few years in Maryland, returned to Virginia and taught at the Howland School. When Emily was in advanced age, she gave the teacher’s cottage she had built and 14 acres of land to Sidney and her husband Chester Boyer.

She was doubtless happier with another of her protéges pictured in the album, Sidney Taliaferro. She was the daughter of freedman Benjamin Taliaferro whose extended family Emily had settled on a large parcel of land she bought in Northumberland County, Virginia. This was her way of keeping the broken “40 acres and a mule” promises. If the government wouldn’t acquire land for freedmen, then she would. She had a school built there, the Howland Chapel School, to educate their children. (The building is still standing today largely unaltered and on the National Register of Historic Places.) Sidney did so well that Emily brought her up north to attend a secondary school run by a relative of hers in New York state and then onto college. She became a school teacher too, and after a few years in Maryland, returned to Virginia and taught at the Howland School. When Emily was in advanced age, she gave the teacher’s cottage she had built and 14 acres of land to Sidney and her husband Chester Boyer.

“Now people in our nation’s capital and around the world can see these important figures from American history and learn more about their lives,” said Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden. “We are proud this historic collaboration with the Smithsonian has made these pictures of history available to the public online.”

The public will have a chance to view the rare album for the first time in person at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in a special exhibit later this year. The digital images also will be presented through the museum’s website.

“This photo album allows us to see Harriet Tubman in a riveting, new way; other iconic portraits present her as either stern or frail. This new photograph shows her relaxed and very stylish. Sitting with her arm casually draped across the back of a parlor chair, she’s wearing an elegant bodice and a full skirt with a fitted waist. Her posture and facial expression remind us that historical figures are far more complex than most people realize. This adds significantly to what we know about this fierce abolitionist. And that’s a good thing,” said Lonnie G. Bunch III, the founding director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.