The Fray Ignacio de Quezada library in the San Augustin Monastery in Quito, Ecuador, is the only library in the Americas housed in its original late 16th century building. It contains 33,500 rare books, manuscripts and incunabula ranging in date from the 15th century through the 20th covering the sciences, literature, music and religion.

The Fray Ignacio de Quezada library in the San Augustin Monastery in Quito, Ecuador, is the only library in the Americas housed in its original late 16th century building. It contains 33,500 rare books, manuscripts and incunabula ranging in date from the 15th century through the 20th covering the sciences, literature, music and religion.

There are 26 extremely rare incunabula — publications created between 1450 and 1500, the first decades after the invention of the printing press in Europe — in the collection. This is the largest number of incunabula in Ecuador, which is one of the reasons the San Augustin library is the most important center of bibliographic heritage in the country.

The oldest book in the collection is an incunabula published in Venice in 1482. Another jewel in the incunabula collection is even more important because of a handwritten inscription that says it belonged to Fray Pedro Bedón (1551-1621), a renown muralist and one of the first artists of the Quiteña School of colonial art.

The oldest book in the collection is an incunabula published in Venice in 1482. Another jewel in the incunabula collection is even more important because of a handwritten inscription that says it belonged to Fray Pedro Bedón (1551-1621), a renown muralist and one of the first artists of the Quiteña School of colonial art.

It also contains other books of immense historical significance, including the polyglot Bible of Paris (1645), a seven-volume Pentateuch written in the oldest known variants of Hebrew, Greek, Samaritan Aramaic, Syriac Aramaic, Targum Aramaic, Latin and Arabic. That’s not the only polyglot Bible in the library. There’s one published in England which features two additional languages: Persian and Ethiopian.

The monastery of San Augustin was damaged in the 7.8 magnitude earthquake that struck off the coast of Ecuador in April 2016. While the epicenter was 110 miles from Quito, some structures collapsed in the quake and there were widespread power failures.

The monastery was already in need of repairs before the earthquake, so it and the literary treasures it guards were highly vulnerable. The ceilings, walls and shelving of the archives were damaged. Leaking water and skyrocketing humidity levels put the books at great risk of destruction, and one strong aftershock could well have caused catastrophic loss. Attempts to restore the roof after the quake put the volumes at even more risk as dirt and debris fell into the monastery interior.

The monastery was already in need of repairs before the earthquake, so it and the literary treasures it guards were highly vulnerable. The ceilings, walls and shelving of the archives were damaged. Leaking water and skyrocketing humidity levels put the books at great risk of destruction, and one strong aftershock could well have caused catastrophic loss. Attempts to restore the roof after the quake put the volumes at even more risk as dirt and debris fell into the monastery interior.

In 2017, the Fundacion Conservartecuador (FC), an NGO dedicated to the conservation of Ecuador’s cultural heritage, requested the aid of the Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development’s Cultural Emergency Response (CER) program. With their financial support, FC was able to triage the collection. They selected the works in most urgent need of attention based on their importance, condition, age, content, author, printer and connection to the culture of the Americas and removed them to a workshop where they were documented, photographed and their immediate conservation needs assessed.

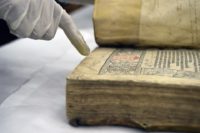

The first step in the ongoing conservation of the books was cleaning them, removing the accumulated dust of centuries and the recent additions in the aftermath of the earthquake. The books were placed in a plastic chamber connected to a filter hoses that gently absorbs particle matter. Working with their hands inside the chamber, conservators used soft, small brushes to carefully clean remaining dust from the pages. That step alone adds decades of life to the books.

The first step in the ongoing conservation of the books was cleaning them, removing the accumulated dust of centuries and the recent additions in the aftermath of the earthquake. The books were placed in a plastic chamber connected to a filter hoses that gently absorbs particle matter. Working with their hands inside the chamber, conservators used soft, small brushes to carefully clean remaining dust from the pages. That step alone adds decades of life to the books.

Thornier issues can then be addressed. Some books have fungi contamination. Some, like 17th century choral books written on vellum and decorated with gold leaf, are highly susceptible to changes in temperature and must have specialized treatment to stabilize their supports. It’s an extremely expensive proposition. Restoring a single choral book, for example, costs around $30,000.

The project has generated unexpected benefits beyond the preservation of these priceless documents. The library’s contents were little known. Having to go through every single holding page by page gave researchers far more insight into and detailed knowledge of the vast resource. They discovered how much historic information was at their fingertips, and the publicity generated by the conservation has drawn international attention to largely forgotten writings documenting the colonization of Ecuador and the cultural practices of indigenous peoples before the Spanish conquest.

The project has generated unexpected benefits beyond the preservation of these priceless documents. The library’s contents were little known. Having to go through every single holding page by page gave researchers far more insight into and detailed knowledge of the vast resource. They discovered how much historic information was at their fingertips, and the publicity generated by the conservation has drawn international attention to largely forgotten writings documenting the colonization of Ecuador and the cultural practices of indigenous peoples before the Spanish conquest.

The publicity also gave the library access to more funding for the long-term management of the its assets, and has become a model for cultural heritage preservation in the country. Universities, museums, government entities and even the military, have all sent personnel to the Monastery to be trained in the latest methods and technologies in the conservation of documentary heritage.