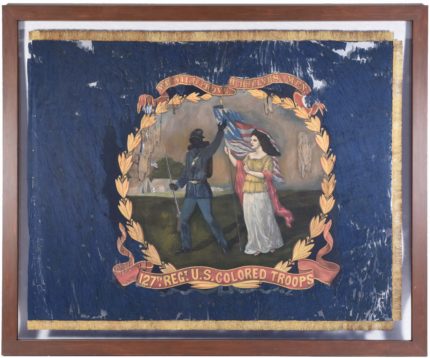

A one-of-a-kind Civil War flag from Pennsylvania’s 127th United States Colored Infantry Regiment is going up for auction this week.

Its imagery is remarkable, depicting a Black troop waving goodbye to Columbia, the Goddess of Liberty, beneath a banner that reads: “WE WILL PROVE OURSELVES MEN.” Below the cartouche is a banner that says: “127th REGt. U.S. COLORED TROOPS.”

The flag was designed and hand-painted by Philadelphia portraitist David Bustill Bowser. He was the son of a fugitive slave father and grandson on his mother’s side of prominent Philadelphia baker, brewer and civic leader Cyrus Bustill, a former slave owned by his own Quaker father. Cyrus Bustill was able to buy his freedom before the Revolutionary War. Like many members of his extended family, David Bowser was politically active in his community. His home was a stop on the Underground Railroad and he made portraits of important abolitionist figures, most famously John Brown a year before the Harper’s Ferry raid. He also designed flags, banners and regalia for political parties, civil rights organizations, fraternal groups and fire companies.

[Entirely random historical flagmaker connection:

David Bowser’s father Jeremiah was a member of the Society of Friends. He had escaped slavery and become a successful businessman in Philadelphia as owner of a popular oyster house and beer seller. His former owners had him arrested in Philadelphia and Friends raised funds to buy his freedom. When his son was born, he named him David after David Newport, one of the Friends who had worked indefatigably to secure Jeremiah’s freedom. David Newport’s grandson, also named David, who had known Jeremiah and David Bowser from early childhood, married Susan Satterthwaite, granddaughter of Betsy Ross.]

As soon as Congress passed the act allowing African Americans to serve in the military, Bowser actively worked to recruit black soldiers. That was July of 1862, but President Lincoln didn’t allow any black troops to serve in combat until the Emancipation Proclamation was issued on January 1st, 1863, and then it took another six months before the War Department created the Bureau of Colored Troops to recruit and deploy black units in an organized fashion. Racism was deeply ingrained in the process. Commissioned officers all had to be white; black soldiers were paid laborers’ wages; their families were rarely granted the financial support white soldiers’ dependents received.

In June of 1863, the Union Army issued an appeal for black soldiers to enlist: “The Government of the United States calls for every able-bodied African-American man to enter the army for three years’ service, and join in fighting the battles of Liberty and the Union.” A week after that proclamation, Camp William Penn, the first federally operated recruitment and training center for black troops, was established on property outside Philadelphia owned by prominent Quaker abolitionist and women’s rights activist Lucretia Mott.

A month later, a Meeting for the Promotion of Colored Enlistments was held in Philadelphia where speakers including Frederick Douglass promoted black men enlisting in the Union Army. Douglass’ clear-eyed, thoughtful explanation of why African Americans should fight for a government and army that had shown such active contempt for them was extremely well-received and recruitment took off in a big way.

Almost 11,000 volunteers made their way to Camp William Penn. Eleven of the new United States Colored Infantry regiments mustered there and the camp’s Supervisory Committee for Recruiting Colored Regiments commissioned Bowser to create their regimental battle flags. Somebody, there are no surviving records indicating who, lodged an objection. All we know about this event is from a letter written by John Weil Forney, an influential Philadelphia politician, to Thomas Webster, chairman of the committee, on March 29th, 1864. Forney wrote:

“While in Philadelphia two days ago, I learned that an effort was being made to deprive Mr. D. B. Bowser of the work of painting the flags of the colored regiments, and I would have called upon you to make an appeal on his behalf had not the weather been so bad. He came to see me, but I was much too occupied to give him a hearing, and he writes me this morning, begging me to intercede with you — which I most earnestly and cheerfully do. He is a poor man, and certainly professes very remarkable talent. He has been active in the cause and is himself a colored man, and it seems to me there would be peculiar hardship in taking away this little job from him and giving it to a wealthy house. Will you do your best for him, and greatly oblige.”

That did the trick. Bowser kept the commission and created one flag for each of the 11 Camp William Penn regiments. The image of Columbia, the personification of the United States as symbol of liberty and justice, accompanied by a black soldier was a recurring motif on Bowser’s flags, perhaps a deliberate needling of Confederate troops who, symbolism aside, would surely have been triggered by the images of a white woman being defended/touched/closely accompanied by a black man. Other low-key burns include the 45th regiment’s flag featured a black soldier waving a US flag in front of a bust of George Washington under the slogan “One Cause, One Country,” and the flag of the 22nd regiment which showed a black soldier bayoneting a Confederate soldier under the banner “Sic semper tyrannis,” (thus always to tyrants), the motto of Virginia and the phrase yelled by John Wilkes Booth on the stage of Ford’s Theater after he shot Abraham Lincoln in the head.

Of the 11 flags Bowser created, only the 127th regiment’s is known to survive today. Seven of them are known from photographic prints. Because United States Colored Troops flags were not issued by state and/or federal government as every other unit’s was, when the Mustering Office closed in June of 1866, the physical flags were returned to the USCT. They were stored in Washington, D.C., until 1906 when they were moved to the museum of the United States Military Academy at West Point. Never exhibited, they were taken out of storage and destroyed in 1942.

Of the 11 flags Bowser created, only the 127th regiment’s is known to survive today. Seven of them are known from photographic prints. Because United States Colored Troops flags were not issued by state and/or federal government as every other unit’s was, when the Mustering Office closed in June of 1866, the physical flags were returned to the USCT. They were stored in Washington, D.C., until 1906 when they were moved to the museum of the United States Military Academy at West Point. Never exhibited, they were taken out of storage and destroyed in 1942.

The 127th flag is believed to have been given to David Bustill Bowser after the war by Camp William Penn’s commander Louis Wagner. Bowser gave it to Post 2 of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a fraternal organization of Union veterans, which eventually became the GAR Civil War Museum and Library. The museum did some work restoring the flag. They are now putting it up for sale via Morphy Auctions, which has done further restoration work to stabilize and preserve this precious and unique survivor. It will go under the hammer on June 13th with a pre-sale estimate of $150,000-$250,000.