The tomb of the Nicholas Rolin, chancellor of the powerful dukedom of Burgundy in the 15th century, may have been discovered at the site of the church of Notre-Dame-du-Châtel in Autun. The church itself was a casualty of the French Revolution, and Nicholas’ remains were assumed to be lost, if not destroyed. A preventive excavation of the site, now the Place Saint-Louis, in advance of expansion of the Rolin Museum into the old prison and courthouse that border the square unearthed the jumbled bones of at least eight individuals in what had been the crypt of the church. One key artifact was found in the mix: a spur like the one Rolin had specified as part of his burial outfit.

The tomb of the Nicholas Rolin, chancellor of the powerful dukedom of Burgundy in the 15th century, may have been discovered at the site of the church of Notre-Dame-du-Châtel in Autun. The church itself was a casualty of the French Revolution, and Nicholas’ remains were assumed to be lost, if not destroyed. A preventive excavation of the site, now the Place Saint-Louis, in advance of expansion of the Rolin Museum into the old prison and courthouse that border the square unearthed the jumbled bones of at least eight individuals in what had been the crypt of the church. One key artifact was found in the mix: a spur like the one Rolin had specified as part of his burial outfit.

“Fairly consistent clues allow us to confirm that this is indeed Nicolas Rolin’s cellar,” says Yannick Labaune. The certainties of archaeologists are based in particular on the presence of a spur that belonged to the illustrious chancellor of the 15th century. The presence of this spur appears in the testimonies and descriptions of the burial of Nicolas Rolin. “We also know that he was buried with a sword and a dagger, but archaeologists have not found them,” said Vincent Chauvet, Mayor of Autun. And to formulate the hypothesis that these two pieces were stolen during a looting during the dismantling of Notre Dame du Chatel.

Studies will continue in the laboratory in order to carry out DNA analyzes as well as Carbon 14 dating, in particular on the eight skulls found in the tomb. This work will provide more details and above all confirm, even if there is little doubt, that the tomb is indeed that of Nicolas Rolin. The scene will be photographed from different points of view in order to use the technique of photogrammetry and to preserve 3D images.

Born of modest bourgeois parents in Autun in 1376, Nicholas Rolin became and lawyer and vaulted over the restrictive social hierarchies of the Burgundian court to become chancellor to Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy. He served 40 years in the role and amassed a huge amount of wealth, titles, properties and honors on the way. He dispensed as well as he amassed; spending heavily on luxuries, the showier the better, artworks and charitable endeavors. He was a major patron of the Church, erecting churches, endowing new religious orders.

Born of modest bourgeois parents in Autun in 1376, Nicholas Rolin became and lawyer and vaulted over the restrictive social hierarchies of the Burgundian court to become chancellor to Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy. He served 40 years in the role and amassed a huge amount of wealth, titles, properties and honors on the way. He dispensed as well as he amassed; spending heavily on luxuries, the showier the better, artworks and charitable endeavors. He was a major patron of the Church, erecting churches, endowing new religious orders.

Notre-Dame-du-Châtel was a small parish church, not the city’s glamorous cathedral, but it was personally important to Nicholas. He was baptized there and his maternal family had donated an altar in the church’s side chapel of St. Sebastian. The church was in poor condition by the 1420s and Rolin used his money and influence to shore it back up, starting with a reconstruction of the family chapel and in 1431, the reconstruction of the entire church. He then pulled strings with the Pope to have the church’s status promoted from parish to collegiate (administered by a college of canons).

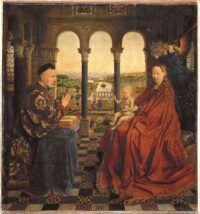

Around 1435, Nicholas Rolin commissioned a portrait from no lesser a master than Jan van Eyck, court painter of Philip the Good, to adorn the family chapel. He is depicted praying in front of the Virgin Mary and the infant Christ as the latter blesses him. It connects Rolin’s wealth (the opulent clothing and surroundings, vineyards in the background) and political success (the Treaty of Arras ending the Hundred Years’ War had just been signed with terms very much to Burgundy’s advantage) to his religious devotion and the direct favor of God.

Around 1435, Nicholas Rolin commissioned a portrait from no lesser a master than Jan van Eyck, court painter of Philip the Good, to adorn the family chapel. He is depicted praying in front of the Virgin Mary and the infant Christ as the latter blesses him. It connects Rolin’s wealth (the opulent clothing and surroundings, vineyards in the background) and political success (the Treaty of Arras ending the Hundred Years’ War had just been signed with terms very much to Burgundy’s advantage) to his religious devotion and the direct favor of God.

(Naughty interlude: in 1431, the same year he funded the reconstruction of Notre-Dame-du-Châtel in Autun, Nicholas Rolin founded a Celestine convent in Avignon with his first son Jean, Bishop of Autun and future Cardinal, as co-founder. Jean, who shared his father’s thirst for all the luxuries the profane world had to offer, impregnated one of the nuns in that convent. Their son, also named Jean, would follow in his father’s and grandfather’s footsteps. A cleric, he served ambassador to the Holy See and to the court of King Charles VIII, the latter of whom legitimized his birth and made him his councilor. Jean’s last appointment was as Bishop of Autun, just like dear old dad.)

Nicholas Rolin died in 1462. He left detailed instructions for his funeral from the rites — three days of mourning “in public view of everyone” — down to the clothes he wanted to ear — white shirt, doublet, a velvet robe with a hood at the neck, a hat with a gold brooch pinned to the front, a sword on his side, a dagger on his other side, new shoes on his feet and gold spurs on his heels.

Nicholas Rolin died in 1462. He left detailed instructions for his funeral from the rites — three days of mourning “in public view of everyone” — down to the clothes he wanted to ear — white shirt, doublet, a velvet robe with a hood at the neck, a hat with a gold brooch pinned to the front, a sword on his side, a dagger on his other side, new shoes on his feet and gold spurs on his heels.

The church was demolished in 1793 and its building materials reused. The Van Eyck portrait was saved, thankfully, and eventually made its way to Louvre in 1805, despite numerous petitions from Autun citizens to Napoleon’s brother Lucien (who had gone to school in Autun) and Talleyrand (the former Bishop of Autun) asking for the masterpiece to be returned to the city. The oil-on-panel painting was intact, but it was missing its original frame which had borne Van Eyck’s signature and the date. The people buried inside the church, including Nicholas Rolin and his family, were given far less consideration. The burials were looted for any valuables and the bones discarded.

The bones that have been discovered at the church site will now be analyzed in the hope that Rolin’s remains might be identified. There’s no way of knowing right now whether his bones are even in the mix. Lots of people were buried in the church over the centuries, and the revolutionaries could just as easily have destroyed or tossed out Nicholas’ remains. The spur, which stylistically dates to the 15th century, is really the only link to him, and that’s tenuous because surely he was not the only man to be buried wearing spurs.

The bones that have been discovered at the church site will now be analyzed in the hope that Rolin’s remains might be identified. There’s no way of knowing right now whether his bones are even in the mix. Lots of people were buried in the church over the centuries, and the revolutionaries could just as easily have destroyed or tossed out Nicholas’ remains. The spur, which stylistically dates to the 15th century, is really the only link to him, and that’s tenuous because surely he was not the only man to be buried wearing spurs.