The 14th century Church of Santa Luciella ai Librai in Naples’ ancient historic center is one of the architectural and artistic gem boxes of the city. Beneath the majolica tile floor, through the sacristy and down a staircase is a hypogeum containing dozens of skulls arranged along shelves high on the walls. One of them has ears.

The 14th century Church of Santa Luciella ai Librai in Naples’ ancient historic center is one of the architectural and artistic gem boxes of the city. Beneath the majolica tile floor, through the sacristy and down a staircase is a hypogeum containing dozens of skulls arranged along shelves high on the walls. One of them has ears.

The small church was founded around 1327 by Bartholemew of Capua, legal and political adviser to Charles II of Anjou, then king of Naples. By 1629 it was dedicated to the guild of millers, but shortly thereafter it switched to the pipernieri, the sculptors who carved piperno marble and other hard stones. They dedicated the church to Saint Lucy, protector of eyesight, to keep their eyes safe from the sharp fragments that flew everywhere when they chiseled stone.

For centuries the eared skull in the basement was venerated, a unique example of Naples’ cult of souls of in Purgatory. People would sort of adopt the disarticulated skull of an unknown and pray for its abandoned soul. That soul, once lifted out of Purgatory into Paradise, would then return the favor by extending grace to the person who had helped them get there. The skull with ears held special attraction because its auricular appendages, believed to be ear cartilage that was naturally mummified, could “hear” the prayers and petitions for grace.

For centuries the eared skull in the basement was venerated, a unique example of Naples’ cult of souls of in Purgatory. People would sort of adopt the disarticulated skull of an unknown and pray for its abandoned soul. That soul, once lifted out of Purgatory into Paradise, would then return the favor by extending grace to the person who had helped them get there. The skull with ears held special attraction because its auricular appendages, believed to be ear cartilage that was naturally mummified, could “hear” the prayers and petitions for grace.

Santa Luciella was taken over by another confraternity in 1748 which extensively refurbished it. The current configuration of the church largely dates to this period. It was still in use until the end of the 20th century. The earthquake that devastated Naples in 1980 heavily damaged the church and it was closed for safety reasons. The church was abandoned and the skull with ears became relegated to the ranks of legend.

Santa Luciella was taken over by another confraternity in 1748 which extensively refurbished it. The current configuration of the church largely dates to this period. It was still in use until the end of the 20th century. The earthquake that devastated Naples in 1980 heavily damaged the church and it was closed for safety reasons. The church was abandoned and the skull with ears became relegated to the ranks of legend.

It re-emerged as fact when a local organization restored the church and reopened it in 2019. They found the fabled eared skull in the hypogeum, unmoved and undamaged by the earthquake. Researchers have embarked on a new multidisciplinary study of the unique piece. Analysis found that the skull consists of the braincase and nasal bones. It belonged to an adult male who suffered from Porotic hyperostosis, a condition that causes spongy or porous tissue on the cranium, likely the result of chronic malnutrition. He is also missing a sagittal suture. Radiocarbon testing dates the remains to between 1631 and 1668. Naples was struck by a terrible outbreak of plague in 1656, so it’s possible our eared friend was one its many thousands of victims.

It re-emerged as fact when a local organization restored the church and reopened it in 2019. They found the fabled eared skull in the hypogeum, unmoved and undamaged by the earthquake. Researchers have embarked on a new multidisciplinary study of the unique piece. Analysis found that the skull consists of the braincase and nasal bones. It belonged to an adult male who suffered from Porotic hyperostosis, a condition that causes spongy or porous tissue on the cranium, likely the result of chronic malnutrition. He is also missing a sagittal suture. Radiocarbon testing dates the remains to between 1631 and 1668. Naples was struck by a terrible outbreak of plague in 1656, so it’s possible our eared friend was one its many thousands of victims.

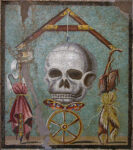

The ears held the real surprises. They were not the product of ossified or mummified ear cartilage. Instead they were formed by the squamous portion of the temporal bone at the side of the head were rotated so the curved edges pointed outwards. This gave the skull ear-like protuberances reminiscent of the famous memento mori mosaic from Pompeii that is now in Naples’ National Archaeological Museum.

The ears held the real surprises. They were not the product of ossified or mummified ear cartilage. Instead they were formed by the squamous portion of the temporal bone at the side of the head were rotated so the curved edges pointed outwards. This gave the skull ear-like protuberances reminiscent of the famous memento mori mosaic from Pompeii that is now in Naples’ National Archaeological Museum.