The first comprehensive study of the mummified bodies of children in the Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo, Sicily, will shed new light on the lives and deaths of the children of late modern Palermo. The catacombs contain the largest collection of mummified human remains in Europe — at least 1,284 individuals. Of these, 163 are children, including 41 in a single room designated to house children’s remains.

The first comprehensive study of the mummified bodies of children in the Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo, Sicily, will shed new light on the lives and deaths of the children of late modern Palermo. The catacombs contain the largest collection of mummified human remains in Europe — at least 1,284 individuals. Of these, 163 are children, including 41 in a single room designated to house children’s remains.

There are written records documenting the dead of Palermo’s Capuchin Catacombs, but they are sparse, often listing only the name and death date of the adults. Past studies of the catacomb’s denizens have revealed unrecorded details — heath, cause of death, profession, social position — about the people laid to rest there from the late 18th to early 20th century. However, this will be the first study to examine the children exclusively.

Researchers will begin by using a portable X-ray machine to scan the remains of the 41 children in the Children’s Room. Fourteen radiographic images will be taken per mummy. The data from the X-rays will allow the research team to create a biological profile of each child — age, sex, any developmental problems they may have suffered, indicators of physical stress and pathologies. This information will be compared with their clothing, placement in the room, funerary objects associated with them and mummification type to find out what children were granted mummification and special placement in Palermo between 1787 and 1880.

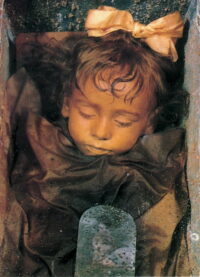

With few exceptions, like the famous “sleeping beauty” Rosalia Lombardo who died in 1920, the childrens identities are not documented. The descriptive tags once attached to them or their belongings have been lost. The study hopes to be able to identify the children by cross-referencing their physical characteristics with archival records of the names and death years.

With few exceptions, like the famous “sleeping beauty” Rosalia Lombardo who died in 1920, the childrens identities are not documented. The descriptive tags once attached to them or their belongings have been lost. The study hopes to be able to identify the children by cross-referencing their physical characteristics with archival records of the names and death years.

Almost all the research until today has been on the adult mummies, excepting a headline-grabbing examination of Rosalia Lombardo, who died of pneumonia a week shy of her second birthday on 6 December 1920.

Her startlingly complete preservation was investigated a decade ago by Dr Dario Piombino-Mascali, who is working with Squires on the latest project at the catacombs.

He said: “Many of the mummies are a result of natural dehydration. Other mummies were chemically treated. Those chemically treated are normally better preserved.

“Some of them are superbly preserved. Some really look like sleeping children. They are darkened by the time but some of them have got even fake eyes so they seem to be looking at you. They look like tiny little dolls.”

After much planning and COVID-related complications, field work is expected to start this month. The x-rays are expected to take a week to complete.