A new exhibition about the history of polychromy on Greek and Roman sculpture opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on Tuesday. Chroma: Ancient Sculpture in Color looks at newly-discovered evidence of polychromy on artworks in the Met’s own collection and reconstructions of how the colorful original may have looked based on the new data. Reconstructions of major works from other collections — for example the Riace bronzes and the Boxer at Rest — are also displayed in the exhibition.

A new exhibition about the history of polychromy on Greek and Roman sculpture opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on Tuesday. Chroma: Ancient Sculpture in Color looks at newly-discovered evidence of polychromy on artworks in the Met’s own collection and reconstructions of how the colorful original may have looked based on the new data. Reconstructions of major works from other collections — for example the Riace bronzes and the Boxer at Rest — are also displayed in the exhibition.

The exhibition features a series of reconstructions of ancient sculptures in color by Prof. Dr. V. Brinkmann, Head of the Department of Antiquity at the Liebieghaus Sculpture Collection, and Dr. U. Koch-Brinkmann, and introduces a new reconstruction of The Met’s Archaic-period Sphinx finial, created by The Liebieghaus team in collaboration with The Met. Presented alongside original Greek and Roman works representing similar subjects, the reconstructions are the result of a wide array of analytical investigations, including 3D imaging, and art historical research. Polychromy is a significant area of study for The Met, and the Museum has a long history of investigating, preserving, and presenting manifestations of original color on ancient statuary.

Displayed throughout the Museum’s Greek and Roman galleries, the exhibition explores four main themes: the discovery and identification of color and other surface treatments on ancient works of art; the reconstruction and interpretation of polychromy on ancient Greek and Roman sculpture; the role of polychromy in conveying meaning within Greek and Roman contexts; and the reception of polychromy in later periods.

Chroma emphasizes the extensive presence and role of polychromy in ancient Mediterranean sculpture, both broadly and across media, geographies, and time periods, from Cycladic idols of the third millennium B.C. to Imperial Roman portraiture of the second century, as witnessed throughout the Museum’s collection and illustrated with 40 artworks in the permanent galleries on the first floor of the Museum. Fourteen reconstructions of Greek and Roman sculpture by Dr. Brinkmann and his team highlight advanced scientific techniques used to identify original surface treatments. These full-size physical reconstructions will be juxtaposed with comparable original works of art throughout The Met’s Greek and Roman Art Galleries, provoking visitors to rethink how the Greek and Roman sculptures originally looked in antiquity.

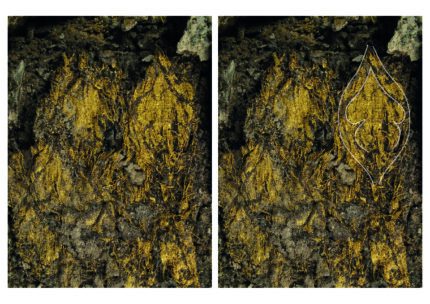

One of the focal artworks in the exhibition is a marble funerary stele from the Archaic period (ca. 530 B.C.) featuring the relief of a youth and topped by a finial in the form of a sphinx. The sphinx retains unusually abundant remnants of red, black and blue paint, and Brinkmann’s team studied it with multi-spectral imaging, photographic techniques and other scientific analyses to reconstruct the original color almost completely. An Augmented Reality app has been created for visitors with smartphones to recreate the sphinx finial in full color while they observe the sphinx as it is today.

The show also ties in artifacts that attest to the ancient love of bright color, like depictions on Greek terracotta vases of polychrome sculpture, a scene of an artist with a brush painting a sculpture carved into an intaglio gemstone, even the beautifully frescoed walls of a bedroom from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale near Pompeii that depict a vividly painted architectural landscape.

This video looks at how Brinkmann and Koch-Brinkmann studied the originals to create the color reconstructions. It’s also very cool to see how the traces of ancient paint appear on the sphinx finial under different lighting conditions.

This video is a digital reconstruction of polychromy built up on the sculpture of a head, likely of Athena. It gives an all-too-brief glimpse into how Egyptian blue pigment was used in the creation of realistic skin tones.