The exploration of the wreck of the 15th century Danish royal warship Gribshunden has uncovered a unique late medieval weapons chest. It is a zeuglade, an ammunition storage and production toolbox that we know from illustrations around that time often accompanied armies on battlefields.

The exploration of the wreck of the 15th century Danish royal warship Gribshunden has uncovered a unique late medieval weapons chest. It is a zeuglade, an ammunition storage and production toolbox that we know from illustrations around that time often accompanied armies on battlefields.

Gribshunden sank in the Blekinge archipelago after a fire broke out when it was anchored off the Baltic coast of southern Sweden in 1495. The royal flagship was carrying King Hans of Denmark and Norway, but he and his retinue had already disembarked on their way to meet with the regent of Sweden when the ship caught fire. About 100 German mercenaries were still on board and went down with the ship. The zeuglade was likely theirs.

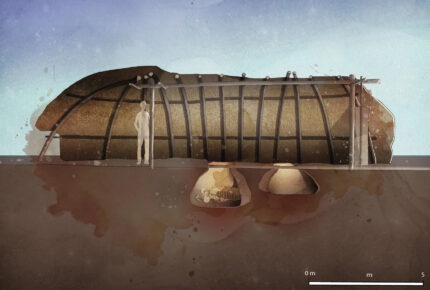

The wreck was discovered in 1971 by scuba divers, but archaeologists didn’t begin to explore the site until 30 years later. The cold Baltic waters had preserved the organic remains of the ship and its cargo in good condition. In 2002, it was identified as the Gribshunden by its unusually large size, carvel construction and heavy armaments. Dendrochronological analysis and radiocarbon dating of the timbers confirmed the identification. The ship made international news in 2015 when the dramatic figurehead was raised from the seabed.

The wreck was discovered in 1971 by scuba divers, but archaeologists didn’t begin to explore the site until 30 years later. The cold Baltic waters had preserved the organic remains of the ship and its cargo in good condition. In 2002, it was identified as the Gribshunden by its unusually large size, carvel construction and heavy armaments. Dendrochronological analysis and radiocarbon dating of the timbers confirmed the identification. The ship made international news in 2015 when the dramatic figurehead was raised from the seabed.

Excavations have been ongoing for more than two decades. The weapon chest was first spotted by archaeologists exploring the wreck in 2019. They returned to the spot in 2023 to document it thoroughly with new high-resolution photos and create a 3D photogrammetry model of the chest. It is approximately 2.3 feet long by one feet wide and is located on the port side of the bow. There is a corrosion crust on the surface and the contents are also heavily corroded, but archaeologists were able to distinguish sharp flint pieces from canister shot ammunition, two elongated pieces of lead plate with holes on the side and three stone molds to manufacture lead bullets of different calibers for handheld firearms and arquebuses. Small cylindrical objects in the chest are believed to be the remnants of crucibles, powder chambers and/or cartridges.

Excavations have been ongoing for more than two decades. The weapon chest was first spotted by archaeologists exploring the wreck in 2019. They returned to the spot in 2023 to document it thoroughly with new high-resolution photos and create a 3D photogrammetry model of the chest. It is approximately 2.3 feet long by one feet wide and is located on the port side of the bow. There is a corrosion crust on the surface and the contents are also heavily corroded, but archaeologists were able to distinguish sharp flint pieces from canister shot ammunition, two elongated pieces of lead plate with holes on the side and three stone molds to manufacture lead bullets of different calibers for handheld firearms and arquebuses. Small cylindrical objects in the chest are believed to be the remnants of crucibles, powder chambers and/or cartridges.

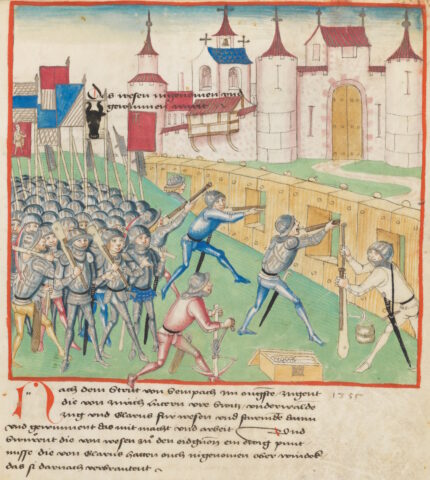

Here’s an illustration of a zeuglade in action on the battlefield from Diebold Schilling’s Amtliche Berner Chronik, Vol. 1, the three-volume official chronicle of Bern completed in 1483. The chest contains paper cartridges and balls to load the arquebuses the infantrymen are shooting.

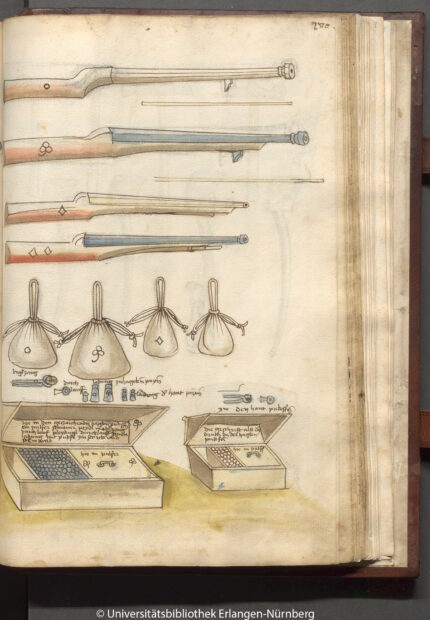

This illustration from a ca. 1500 combat and warfare manual by German knight Ludwig VI von Eyb shows different types of arquebuses and their corresponding ammunition in a zeuglade.

The work to reconstruct the Gripen/Griphund has been going on since 2013. Right now the efforts are focused on the superstructure. In his doctoral thesis, Rolf Warming is also working on clarifying the ship’s combat capabilities and the role of the soldiers on board.

“The ship is an important piece of the puzzle in the ‘military revolution at sea’ in early modern times where the primary tactic shifted from close combat to the difficult naval artillery. The ship will therefore also be compared with other important warships to understand the development, for example Mars (1564) and Vasa (1628),” says Rolf Warming.