The largest surviving bronze statue from antiquity is undergoing a comprehensive restoration program in public view at the Vatican Museums in Rome. The Hercules Mastai Righetti is more than 13 feet tall and is gilded head to toe, an incredibly rare survival of a colossal bronze and even more incredibly rare survival of the full gold layer on a gilded ancient statue. Its otherworldly shine has dulled over the years, however, darkened by coatings of wax applied in the initial restoration after its discovery in the 19th century.

The largest surviving bronze statue from antiquity is undergoing a comprehensive restoration program in public view at the Vatican Museums in Rome. The Hercules Mastai Righetti is more than 13 feet tall and is gilded head to toe, an incredibly rare survival of a colossal bronze and even more incredibly rare survival of the full gold layer on a gilded ancient statue. Its otherworldly shine has dulled over the years, however, darkened by coatings of wax applied in the initial restoration after its discovery in the 19th century.

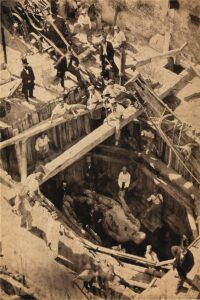

The statue first came to light in 1864 during work on the foundations of the Palazzo Pio Righetti, a 15th century palace on the Campo de’ Fiori that had recently been acquired by wealthy banker Pietro Righetti. Under the palace courtyard, workmen encountered an ancient wall and a bronze finger. The finger was so big that the statue it was attached to had to have been monumental in scale.

A subsequent excavation dug down 15 feet to find a wall of peperino (a grey volcanic tuff) flanked by columns believed to have been part of the foundation of the temple of Venus Victrix built by Pompey as a religious pretext to construct the first permanent theater in Rome attached to it.

A subsequent excavation dug down 15 feet to find a wall of peperino (a grey volcanic tuff) flanked by columns believed to have been part of the foundation of the temple of Venus Victrix built by Pompey as a religious pretext to construct the first permanent theater in Rome attached to it.

(Today the remains of Pompey’s Theater underneath the Palazzo Pio Righetti have been incorporated into a restaurant that serves traditional Roman food in what is basically an underground archaeological park. I recommend the oxtail.)

Inside a ditch surrounded by travertine slabs was the colossal gilded bronze statue lying on its side. His feet were broken and the back of his head was missing, as were his genitals. It likely dates to between the end of the 1st century and the beginning of the 3rd, and is believed to be a copy of a Greek original from the late 4th century B.C.

Under the statue the diggers founds fragment of the skin of the Nemean lion, the broken right foot, fragments of the club Hercules used to slay the lion and a triangular slab of travertine inscribed “F C S.” The initials stand for “fulgor conditum summanium,” meaning “here lies a lightning bolt from Summanus.” These three little letters are a key clue to the statue’s fate: it had been struck by a thunderbolt at night (Summanus was the god of nocturnal thunder), which, according to an ancient Roman belief descended from the Etruscans, rendered the strike site a sacred area where any electrocuted objects had to be buried immediately.

Under the statue the diggers founds fragment of the skin of the Nemean lion, the broken right foot, fragments of the club Hercules used to slay the lion and a triangular slab of travertine inscribed “F C S.” The initials stand for “fulgor conditum summanium,” meaning “here lies a lightning bolt from Summanus.” These three little letters are a key clue to the statue’s fate: it had been struck by a thunderbolt at night (Summanus was the god of nocturnal thunder), which, according to an ancient Roman belief descended from the Etruscans, rendered the strike site a sacred area where any electrocuted objects had to be buried immediately.

Three months after its discovery, the bronze was bought by Pope Pius IX for the Vatican Museums collection. In 1866, the Hercules Mastai Righetti was installed in the Round Hall of the Pio Clementino Museum and has been there ever since. Visitors to the museum now have the opportunity to see Hercules’ shine restored before their eyes.

Three months after its discovery, the bronze was bought by Pope Pius IX for the Vatican Museums collection. In 1866, the Hercules Mastai Righetti was installed in the Round Hall of the Pio Clementino Museum and has been there ever since. Visitors to the museum now have the opportunity to see Hercules’ shine restored before their eyes.

“The original gilding is exceptionally well-preserved, especially for the consistency and homogeneity,” Vatican Museum restorer Alice Baltera said. […]

The burial protected the gilding, but also caused dirt to build up on the statue, which Baltera said is very delicate and painstaking to remove. “The only way is to work precisely with special magnifying glasses, removing all the small encrustations one by one,” she said.

The work to remove the wax and other materials that were applied during the 19th-century restoration is complete. Going forward, restorers plan to make fresh casts out of resin to replace the plaster patches that covered missing pieces, including on part of the nape of the neck and the pubis.

The most astonishing finding to emerge during the preliminary phase of the restoration was the skill with which the smelters fused mercury to gold, making the gilded surface more enduring.

“The history of this work is told by its gilding. … It is one of the most compact and solid gildings found to date,’’ said Ulderico Santamaria, a University of Tuscia professor who is head of the Vatican Museums’ scientific research laboratory.