The National Museum of Sweden has acquired an iconic portrait miniature of the 28-year-old Count Hans Axel von Fersen (1755–1810), Swedish diplomat and lover of Queen Marie-Antoinette of France. Long held by descendants of the Fersen family, it went under the hammer in June and sold for 8,376 EUR ($9,112), three times its pre-sale estimate. As with the gold box with a portrait of King Gustavus III, the museum was able to acquire the miniature thanks to a donation from the Anna and Hjalmar Wicander Foundation.

The portrait is a bust from the left with Fersen’s face turned towards the viewer. He wears a grey coat with a striped red waistcoat peeking out of the lapels. It is a gouache watercolor painted on ivory and mounted in a brass frame. Mounted in its frame, it is a rectangle two inches long and 1.7 inches wide.

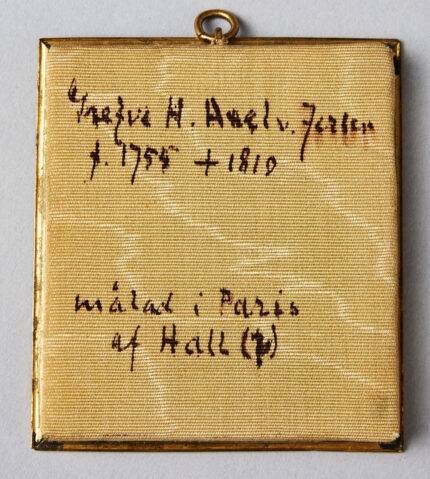

The painter in unknown. A handwritten note on the back attributes the portrait to Peter Adolf Hall, a Swedish-French miniaturist who painted several members of the royal families of France, both before and after the Revolution. The National Museum, however, notes that it was painted in London, not Paris, when Fersen was in England in the summer of 1778. The distinctive combination of lines and pointillistic shading in brown shades is characteristic of English portraiture of the period, not French. There are very few portraits of Swedes done in England by English artists in the second half of the 18th century, and none where the sitter is so famous.

Why did the young Fersen commission this portrait of himself during his time in London? Did it have something to do with his intended marriage to Catharina, the daughter of Henrik Leijel (Henry Lyell), a wealthy Swedish-British merchant? Nothing came of this prospective marriage of convenience. Instead, Fersen returned to Paris and embarked on a military career. Two years later, he travelled to North America as aide-de-camp to the head of the French expeditionary force, General Count de Rochambeau. Fersen’s knowledge of English proved very useful in this role, since General George Washington did not speak French. For three years, Fersen acted as interpreter between the allies in their war against the British colonial power. […]

Magnus Olausson, emeritus director of collections at Nationalmuseum, said:

“The portrait of the young Axel von Fersen represents a rare interlude in 18th-century Swedish-British relations. As far as we know, few Swedes were immortalised by British artists in those days.

This iconic portrait of Fersen is an unusually fine work by an unknown British miniaturist, in a style somewhat reminiscent of stipple engraving, which was the great innovation of the time.”