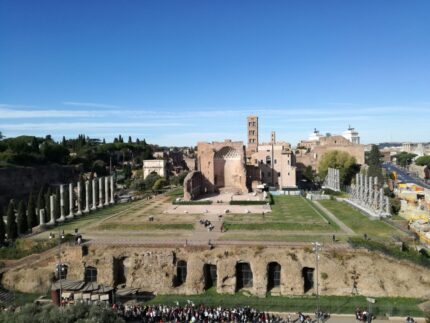

The remains of the Temple of Venus and Rome, the largest sacred building ever constructed in the Eternal City, have reopened to the public after a major restoration project funded by fashion house Maison Fendi.

The remains of the Temple of Venus and Rome, the largest sacred building ever constructed in the Eternal City, have reopened to the public after a major restoration project funded by fashion house Maison Fendi.

The Temple of Venus and Rome was personally designed by Emperor Hadrian and constructed at his command between 121 and 137 A.D. on a high platform on the Velia hill overlooking the Colosseum. The colossus that gives the Flavian Amphitheater its name today stood on that site, originally placed there by Nero. Hadrian had it moved to a new location aside the Colosseum to make way for his massive new temple. It took 24 elephants to move the statue.

Hadrian’s innovative idea to celebrate the goddesses Venus Felix and Roma Aeterna was to build the two cellae (the sacred rooms where the statues of the goddesses sat and only the clergy were allowed) back-to-back instead of the traditional side-to-side configuration. Trajan’s famous architect Apollodorus of Damascus was not a fan, so naturally Hadrian had him killed.

Maxentius ditched Hadrian’s cella design when he rebuilt the temple after it was devastated by fire in 307 A.D. He reconstructed it with two apses covered by coffered vault roofs made of stone instead of the original wood ceilings. He also added porphyry columns to the Proconnesian marble columns in the porticoes and the grey granite columns in the peristyle.

Maxentius ditched Hadrian’s cella design when he rebuilt the temple after it was devastated by fire in 307 A.D. He reconstructed it with two apses covered by coffered vault roofs made of stone instead of the original wood ceilings. He also added porphyry columns to the Proconnesian marble columns in the porticoes and the grey granite columns in the peristyle.

The temple was converted into an oratory dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul in the 8th century, but most of the immense structure was destroyed by an earthquake in the 9th century. The church of Santa Maria Nova, and later Santa Francesca Romana, rose from the ruins.

Today the remains left standing on the platform are from Maxentius’ reconstruction. The porphyry columns and marble inlay floors and walls were reassembled from fragments in the 1930s. There’s also a convent and the offices of the Archaeological Park of the Colosseum integrated into the site.

The Colosseum Park has put together a great video that explains the history (narration is in Italian but captions are bilingual in English and Italian) and virtually reconstructs the enormous temple, placing it in the context of the modern city.