In the fall of 2003, archaeologists surveying the site of future road widening project near Prittlewell, south Essex, spotted a piece of bronze sticking up out of the ground. The ensuing excavation found that the bit of bronze marked the spot of an Anglo-Saxon chamber burial of exceptional wealth and historical significance. While the skeletal remains were gone, devoured by the acidic soil that had made its way into the wooden sides of the tomb, more than 60 objects were found, among

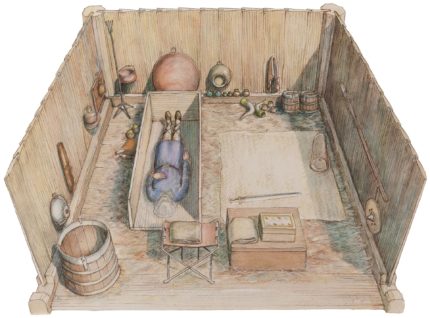

In the fall of 2003, archaeologists surveying the site of future road widening project near Prittlewell, south Essex, spotted a piece of bronze sticking up out of the ground. The ensuing excavation found that the bit of bronze marked the spot of an Anglo-Saxon chamber burial of exceptional wealth and historical significance. While the skeletal remains were gone, devoured by the acidic soil that had made its way into the wooden sides of the tomb, more than 60 objects were found, among  them an iron folding stool, several bronze vessels, drinking cups made of wood (some surviving) and gold, blue glass jars, a gold buckle, gold foil crosses, traces of a wood lyre, a sword and shield. The chamber was in such good condition that copper-alloy bowls were found still hanging from hooks in the walls. All of the grave’s many furnishings were in the original position they’d been placed in on the day of the burial.

them an iron folding stool, several bronze vessels, drinking cups made of wood (some surviving) and gold, blue glass jars, a gold buckle, gold foil crosses, traces of a wood lyre, a sword and shield. The chamber was in such good condition that copper-alloy bowls were found still hanging from hooks in the walls. All of the grave’s many furnishings were in the original position they’d been placed in on the day of the burial.

The richness of the grave goods and the size of the burial chamber (13 feet square and five feet high) strongly suggested the deceased was someone of great importance, likely royalty. The placement of the gold foil crosses pointed to them having been laid on the body, perhaps the eyes, or stitched to a shroud that covered it. Archaeologists hypothesized that the deceased was an Anglo-Saxon king on the cusp of the transition from paganism to Christianity. The crosses were symbols of his new religion, but the plethora of grave goods were a nod to traditional funerary practices which furnished graves with objects of use to the deceased in the afterlife and ones symbolizing his rank.

The richness of the grave goods and the size of the burial chamber (13 feet square and five feet high) strongly suggested the deceased was someone of great importance, likely royalty. The placement of the gold foil crosses pointed to them having been laid on the body, perhaps the eyes, or stitched to a shroud that covered it. Archaeologists hypothesized that the deceased was an Anglo-Saxon king on the cusp of the transition from paganism to Christianity. The crosses were symbols of his new religion, but the plethora of grave goods were a nod to traditional funerary practices which furnished graves with objects of use to the deceased in the afterlife and ones symbolizing his rank.

There was some speculation about which king this might have been, and there weren’t a lot of options so the likeliest candidates were Saebert, King of Essex (converted to Christianity in 604, died in 616), or Sigeberht II, King of the East Saxons (converted in 653, died ca. 661).

There was some speculation about which king this might have been, and there weren’t a lot of options so the likeliest candidates were Saebert, King of Essex (converted to Christianity in 604, died in 616), or Sigeberht II, King of the East Saxons (converted in 653, died ca. 661).

A meticulous excavation followed by years of analysis by Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) of the archaeological material from the Prittlewell burial has put the kibosh on both those possibilities. Researchers were able to get radiocarbon dates from the sparse organic remains, wood fragments attached to metal decorations

A meticulous excavation followed by years of analysis by Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) of the archaeological material from the Prittlewell burial has put the kibosh on both those possibilities. Researchers were able to get radiocarbon dates from the sparse organic remains, wood fragments attached to metal decorations  on a drinking horn and wooden cup, using accelerator mass spectroscopy which only requires a miniscule sample of material and yields high-precision results. The Prittlewell burial took place 575 and 605 A.D., excluding both of the candidates believed to have been the first East Saxon kings to convert to Christianity.

on a drinking horn and wooden cup, using accelerator mass spectroscopy which only requires a miniscule sample of material and yields high-precision results. The Prittlewell burial took place 575 and 605 A.D., excluding both of the candidates believed to have been the first East Saxon kings to convert to Christianity.

The radiocarbon date range can be narrowed down a little further from stylistic analysis of the grave goods and coins which point to the burial dating to the last two decades of the 6th century. If true, it could even predate the dawn of Christianity in Essex. St. Augustine of Canterbury arrived to convert the East Saxons in 597. Not that there couldn’t have been

The radiocarbon date range can be narrowed down a little further from stylistic analysis of the grave goods and coins which point to the burial dating to the last two decades of the 6th century. If true, it could even predate the dawn of Christianity in Essex. St. Augustine of Canterbury arrived to convert the East Saxons in 597. Not that there couldn’t have been  less direct avenues to conversion before then. The Britons had been converted to Christianity during Roman rule and while they were completely walled off from the Roman Church by the Anglo-Saxon invasions, they were still there and still Christian. Also, Aethelbert, King of Kent, married a Frankish princess who was not only a Christian but the great-grandaughter of a saint. She brought a bishop with her when they married in 580 A.D. to ensure she could practice her religion and is believed to exerted a great deal of influence on the spread of Christianity in Britain long before the arrival of St. Augustine. Aethelbert’s sister married Saebert’s father.

less direct avenues to conversion before then. The Britons had been converted to Christianity during Roman rule and while they were completely walled off from the Roman Church by the Anglo-Saxon invasions, they were still there and still Christian. Also, Aethelbert, King of Kent, married a Frankish princess who was not only a Christian but the great-grandaughter of a saint. She brought a bishop with her when they married in 580 A.D. to ensure she could practice her religion and is believed to exerted a great deal of influence on the spread of Christianity in Britain long before the arrival of St. Augustine. Aethelbert’s sister married Saebert’s father.

The person’s identity will remain unknown unless some future technology makes it possible to solve the mystery. All that remains of the body are tiny fragments of tooth enamel. The type of buckles and the weapons in the grave suggest the deceased was male, and judging from the placement of the belt buckle, garter buckles and the crosses over his eyes, he was about 5’8″.

The person’s identity will remain unknown unless some future technology makes it possible to solve the mystery. All that remains of the body are tiny fragments of tooth enamel. The type of buckles and the weapons in the grave suggest the deceased was male, and judging from the placement of the belt buckle, garter buckles and the crosses over his eyes, he was about 5’8″.

Even more extraordinary finds were made in the soil of the grave which was lifted en bloc so it could be micro-excavated in the lab. A few scraps of wood from a decayed object thought to be a box lid revealed themselves to be the only known surviving example of early Anglo-Saxon painted woodwork. The maple wood is decorated with a yellow border in a ladder pattern and two ovals, one white, one red, filled with a cross-hatch.

Even more extraordinary finds were made in the soil of the grave which was lifted en bloc so it could be micro-excavated in the lab. A few scraps of wood from a decayed object thought to be a box lid revealed themselves to be the only known surviving example of early Anglo-Saxon painted woodwork. The maple wood is decorated with a yellow border in a ladder pattern and two ovals, one white, one red, filled with a cross-hatch.

There weren’t even scraps of wood left of another one-of-a-kind discovery: an Anglo-Saxon lyre. All that was left of it was a stain in the soil containing tiny bits of wood and two copper discs inlaid with garnets that had riveted the yoke of the lyre to the arm, still in their original positions. The wood of the lyre was maple with a hollow sound box and the tuning pegs were made from ash wood. Raman spectroscopy identified the garnets in the center of the metal fittings as having originated in India or Sri Lanka. There was also a copper vessel from Syria and two gold coins from Merovingian France, so clearly the young man had access to the finest, most expensive imports money could buy.

There weren’t even scraps of wood left of another one-of-a-kind discovery: an Anglo-Saxon lyre. All that was left of it was a stain in the soil containing tiny bits of wood and two copper discs inlaid with garnets that had riveted the yoke of the lyre to the arm, still in their original positions. The wood of the lyre was maple with a hollow sound box and the tuning pegs were made from ash wood. Raman spectroscopy identified the garnets in the center of the metal fittings as having originated in India or Sri Lanka. There was also a copper vessel from Syria and two gold coins from Merovingian France, so clearly the young man had access to the finest, most expensive imports money could buy.

Artifacts found in the Prittlewell burial will go on display at Southend Central Museum starting Saturday, May 11th. To learn more about the burial and its unique treasures, check out the excellent dedicated website MOLA has created.