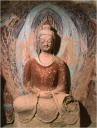

On the edge of the Gobi desert in Western China outside the ancient Silk Road city of Dunhuang is a cliff face bored with hundreds of Buddhist grottoes carved out of the rock face. They’re called Mogaoku (“peerless caves”) and they are packed with unbelievably gorgeous frescoes and sculptures ranging in date from the 5th to the 14th centuries.

On the edge of the Gobi desert in Western China outside the ancient Silk Road city of Dunhuang is a cliff face bored with hundreds of Buddhist grottoes carved out of the rock face. They’re called Mogaoku (“peerless caves”) and they are packed with unbelievably gorgeous frescoes and sculptures ranging in date from the 5th to the 14th centuries.

The caves started as hermit habitats, simple holes carved into the sandstone, but by 50 years after the first monk made himself a rock home in 366 A.D., the caves flourished in number and decor.

Larger and larger grottoes were excavated as temples and monastic lecture halls: essentially, public spaces. Many had chapel-like niches and free-standing walk-around altars, all cut from stone. As with the Ajanta Buddhist caves in India, interiors were carved with architectural features — beams, eaves, pitched roofs, coffered ceiling — as if to simulate buildings.

Painting covered everything. Murals illustrating jatakas, tales from the Buddha’s past lives, were popular; they’re like panoramic comic-book storyboards spread across a wall. For imperially commissioned interiors, images of princeling saints and court fetes were the rule. Rock ceilings were covered with fields of decorative patterning to evoke an illusion of fabric pavilions. Any leftover space was filled with figures of tiny deities — Mogaoku was known as the Thousand Buddha Caves — painted directly on the plastered walls or stuck on as sculptural plaques. […]

Of the 800 or so caves created here from the 5th to 14th centuries, nearly half had some form of decoration. What survives adds up to a developmental timeline of Buddhist art in China, an encyclopedic archive of styles and ideas, of dashes forward and retreats to the past.

So of course it’s in danger of destruction. We have the usual story of scholars/looters stripping hunks off the wall for their hometown museum. Then there’s the desert sand: nature’s most reliable abrasive. Then there are the crowds of people since the site was opened to tourism since 1980, exuding moisture and carbon dioxide.

So of course it’s in danger of destruction. We have the usual story of scholars/looters stripping hunks off the wall for their hometown museum. Then there’s the desert sand: nature’s most reliable abrasive. Then there are the crowds of people since the site was opened to tourism since 1980, exuding moisture and carbon dioxide.

Plans for drastic remedial action are in place. Under Dr. Fan and the vice director, Wang Xudong, the academy will build by 2011 a new visitor reception center several miles from the caves, near the airport and railroad station. All Mogaoku-bound travelers will be required to go to the center first, where they will be given an immersive introduction to the caves’ history, digital tours of interiors and simulated restorations on film of damaged images. They will then be shuttled to the site itself, where they will take in the ambience of its desert-edge locale and see the insides of one or two caves before returning to where they started.

It’s not the familiar model of Western tourism, to be sure, but I think it’s quite brilliant. If site preservation requires draconian measures, then draconian measures there should be. They could have closed the caves. Hell, they still might have to is this doesn’t work.

Be sure to check out the slide show on the article because there isn’t one picture I didn’t want to post. The art is just astonishingly gorgeous.

At the show’s heart is the constantly shifting use of stone, especially the flat pietre dure. Sometimes stone is exploited for its own fabulous color and texture, as in the bold geometric tabletops of papal Rome or a Venetian cabinet that is really more a rock-solid architectural model than it is furniture.

Examples include the fabulously accurate undergrowth of grape vines, butterflies and birds on a table with Eucharistic symbols, and a tiny austere landscape in which single pieces of lapis and agate form sky and hills. Inlaid details like a white church and green poplars sharpen the implicit spatial recession.