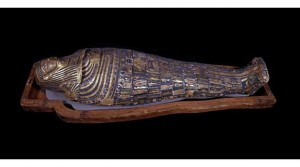

Smugglerius is the cast of an executed criminal which has been used to teach anatomical drawing at the Edinburgh College of Art for generations, but nobody knew anything about it.

Now a new exhibit in conjunction with the restoration of the college’s Art Cast collection lays out the history of Smugglerius the casting and his unfortunate model.

Artist Joan Smith and anthropologist Dr Jeanne Cannizzo from the University of Edinburgh researched the provenance of Smugglerius. They found out he’s a 19th century copy of a cast made in the 18th century from the deceased. They also found out the likely identity of the model, but you have to go to the exhibit to find out ’cause they’re not telling on the website. Yes, I am pouting.

Here’s what we do know.

Dating from 1854, the College Smugglerius is a copy of an original écorché – a figure with the skin and fat removed to expose the muscles and tendons – made in 1776 at Royal Academy of Art in London. This earlier cast, now lost, was moulded from the body of a hanged criminal by the sculptor Agostino Carlini, following its dissection by William Hunter, the famous anatomist. The College cast, which retains the stunning detail of the original, was made by a little known ‘moulder and figure maker’ called William Pink, probably at the time of his employment at the British Museum; an inscription on the base of the cast states “Published by W PINK Moulder 1854”.

Since its arrival at the College, the cast has been used in the teaching of anatomy to art students, much as the original cast would have been used by artists at the Royal Academy, among them William Blake.

The exhibit features not only the history of Smugglerius, but also a variety of art pieces made from his example. It’s a fascinating exploration of the storied relationship between anatomical dissection and artist depictions of the human body, issues of anonymity and identity.

The companion exhibitions of “Smugglerius Unveiled” and “Drawing For Instruction: the art of explanation” will be open from February 2nd to to March 6th. Admission is free. I’d love to hear about it, so if anyone goes, please comment and dish.