As impressive as the work done by the Allied photo reconnaissance airmen in World War II is, they were following in some truly huge contrails. It was World War I that ushered in the era of aerial reconnaissance, and not just from dirigibles (which I already knew about) but from two-seater biplanes. Picture the size of a 1914 camera. Now picture a rickety biplane, just 11 years newer than the one the Wright brothers flew, with one of the pilots holding said giganto-camera over the edge of the plane taking pictures from 12,000 feet in the air.

As impressive as the work done by the Allied photo reconnaissance airmen in World War II is, they were following in some truly huge contrails. It was World War I that ushered in the era of aerial reconnaissance, and not just from dirigibles (which I already knew about) but from two-seater biplanes. Picture the size of a 1914 camera. Now picture a rickety biplane, just 11 years newer than the one the Wright brothers flew, with one of the pilots holding said giganto-camera over the edge of the plane taking pictures from 12,000 feet in the air.

The mere effort of holding the equipment steadily enough to take a crisp picture is mind-boggling. Then on top of that, they had to take photos while fighters on the ground and in other airplanes were shooting at them. The death rate for pilots was higher than for infantry in the trenches. (They weren’t given parachutes because the powers that be decided that would encourage pilots to bail out instead of doing everything in their power to return the plane to safety. Hey, those planes were expensive, dammit! And a lot harder to find than men for the meat grinder.)

Through all of this, the fly boys somehow managed to take millions of reconnaissance pictures, 500,000 surviving in various European archives, which showed enemy positions in a heretofore unknown detail. For the rest of us, the surviving photographs reveal the seismic destruction of World War I in heretofore unknown detail.

Here is the Belgian town of Passchendaele, a charming village north-east of Ypres, in 1916:

That’s the town center along that curving road, with the church right in the middle, houses along the roads and a lovely quilt of farmland and pasture all around.

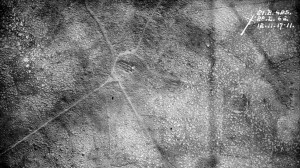

Here is Passchendaele in November, 1917, after the Third Battle of Ypres drenched the area in steel showers off and on for 4 months:

Yeah. What did the Allies gain, you ask, other than a nightmare moonscape in place of a cute village? They gained 5 miles and a 140,000 dead, about 2 inches of ground per dead soldier. The Germans got those 5 miles back without resistance 5 months later.

The Imperial War Museum in London has a large collection of 150,000 WWI aerial photographs. They’ve been sorely underused by historians so far. There hasn’t been a systemic analysis of all the surviving pictures; many of the glass plate negatives haven’t even been printed yet. The BBC will be airing a documentary about these pictures this Sunday, November 7th, at 9:00 PM.