Painter, architect, sculptor and all-around Renaissance Man Michelangelo Buonarotti was born 536 years ago today. Since it’s his birthday and he always considered his foremost talent to be in sculpture despite his fame as a painter, for a present I’m making this entry just about his skill as a stone carver.

His affinity for sculpture was established very early in his life. After Michelangelo’s mother died when he was six, he went to live with a stonecutter and his wife which is where he first began to learn how to chisel rock. His father sent him to school for a while after that, but Michelangelo was only interested in art, so by the time he was 13 he was apprenticed to artist Domenico Ghirlandaio. The boy’s genius was immediately clear. The next year, when he was only 14, Ghirlandaio began to pay him artist wages instead of apprentice wages.

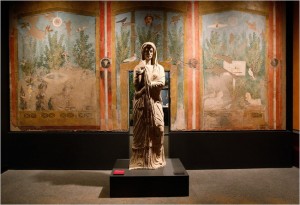

He made this when he was 17 attending the Medici’s Humanist academy in Florence:

It’s the last work he did at the Medici court — Lorenzo died shortly after it was completed — and it’s the first sculpture where the chisel marks are clearly left behind. There’s some debate on whether this was an intentional “unfinished” style or just plain unfinished, but Michelangelo considered it the greatest of his early pieces and it presages the boundary-busting three-dimensionality of his sculptures.

Interesting fun fact about Michelangelo’s sculptural style: since the ancient Greeks, sculptors had chiseled all around a block of stone to create a well-proportioned piece. Michelangelo saw the figure entire trapped in the stone, so he didn’t go around and around. He started at the front and carved all the way to the back, liberating the character from its marble prison. He did it with a speed and accuracy that left his contemporaries slack-jawed.

He was so famous that tourists would go see him work just like they’d visit the Colosseum. A French visitor to Rome during the last years of Michelangelo’s life (he died in 1564) described with awe watching the master, now over 80 years old, at work.

He can hammer more chips out of very hard marble in fifteen minutes than three young stonecarvers can do in three or four hours. It has to be seen to be believed. He went at it with such fury and impetuosity that I thought the whole work would be knocked to pieces. He struck off with one blow chips three or four inches thick, so close to the mark that, if he had gone just a fraction beyond, he would have ruined the entire work.

By then he had been chief architect of St. Peter’s basilica for almost twenty years, since 1546. He designed the famous dome. He would die three weeks before his 88th birthday. The dome wasn’t finished yet, but construction on the lower ring of the cupola had begun so he knew it was too late for them to switch plans and his design would be built.

Michelangelo’s fame was such that he was the first artist to have a biography written about him while he was still alive. The first was a chapter in Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists which you can and should read here (first edition published 1550, so long before Michelangelo died.) This site has snippets of Vasari’s biography accompanied by pictures of the works described.