Just in time for the 310th anniversary of William Kidd’s hanging at Execution Dock in Wapping, along the Thames, the Museum of London Docklands has opened a new exhibit dedicated to the infamous pirate. Pirates: The Captain Kidd Story displays over 170 objects related to Captain Kidd and piracy in general, including an original Jolly Roger pirate flag captured by Midshipman Richard Curry in 1789, a gibbet used to display corpses as a cautionary tale for other would-be criminals, and the silver Admiralty Oar that was carried by the Admiralty Deputy Marshall when leading execution processions. The oar hasn’t been seen in public since the last execution for piracy in 1864.

Just in time for the 310th anniversary of William Kidd’s hanging at Execution Dock in Wapping, along the Thames, the Museum of London Docklands has opened a new exhibit dedicated to the infamous pirate. Pirates: The Captain Kidd Story displays over 170 objects related to Captain Kidd and piracy in general, including an original Jolly Roger pirate flag captured by Midshipman Richard Curry in 1789, a gibbet used to display corpses as a cautionary tale for other would-be criminals, and the silver Admiralty Oar that was carried by the Admiralty Deputy Marshall when leading execution processions. The oar hasn’t been seen in public since the last execution for piracy in 1864.

The most famous of all the pirate booty on display in the exhibit is Captain Kidd’s last letter wherein he claims to have hidden £100,000 (about 5,000 times a sailor’s annual wage) of treasure in a secret Caribbean location. That letter launched many a treasure hunt and inspired literature from Edgar Allan Poe’s The Gold-Bug to Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island. Kidd’s letter is the origin of what is now the most well-worn trope of all pirate movies and adventure novels.

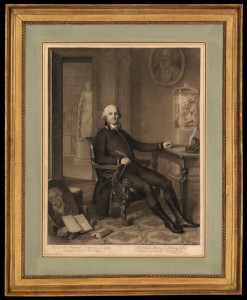

The exhibit doesn’t leave the Captain swinging alone. It makes the argument that high-ranking politicians and businessmen from the American colonies and England were at the very least complicit in the crimes he swung for. His privateering operations attacking French ships in the Caribbean were commissioned by Whig MPs, the English East India Company, the governor of New York, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, Richard Coote, Earl of Bellomont, and even King William III himself, among many others. It was while pursuing these commissions that he committed the act that would ultimately get him hanged from the neck until dead.

On October 30, 1697, gunner William Moore encouraged Kidd to attack a Dutch ship. Kidd refused because that would constitute piracy rather than privateering (it’s all about picking the proper enemy, in this case the French) and because William III was from Orange and thus would not be likely to look upon the attack with favor. Kidd called Moore a lousy dog. Moore said if he was, it was because Kidd made him one. Kidd hit him on the head with an ironclad bucket and Moore died the next day.

On October 30, 1697, gunner William Moore encouraged Kidd to attack a Dutch ship. Kidd refused because that would constitute piracy rather than privateering (it’s all about picking the proper enemy, in this case the French) and because William III was from Orange and thus would not be likely to look upon the attack with favor. Kidd called Moore a lousy dog. Moore said if he was, it was because Kidd made him one. Kidd hit him on the head with an ironclad bucket and Moore died the next day.

Kidd also began to gain a reputation for piratical acts like torturing prisoners and theft, even though it seems that many of these instances were perpetrated by his mutinous crew against his will. It was his capture of the Quedagh Merchant, an Armenian ship sailing under French passes, on January 30, 1698 that sealed his fate. The French passes marked it as fair game for British privateers, but the captain of the ship was English. When news reached home of the capture, the Royal Navy was ordered to capture Kidd and his crew for acts of piracy.

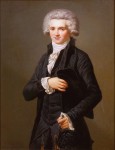

They didn’t catch him, though. It was his investor Bellomont who betrayed him, luring him to Boston with a false offer of clemency then arresting him on July 6, 1699. He remained in jail in Boston for a year before being sent to England for trial on charges of piracy and the murder of Moore. The political tides had shifted and his powerful backers were no longer so powerful. He kept his silence, never naming names, thinking that his loyalty would garner him their help when in fact they ran the other way. Evidence that was material to his defense disappeared, including the French passes proving that the Quedagh Merchant was fair game. They would be found in a London building in 1911, misfiled along with some other government papers.

He was executed by hanging at Execution Dock in Wapping, London on May 23, 1701. They had to hang him twice because the rope broke the first time. Once he was dead, his body was coated in pitch and stuffed into the gibbet — an iron cage that had been made to order to fit him — to serve as warning to all who would follow in his footsteps.

He was executed by hanging at Execution Dock in Wapping, London on May 23, 1701. They had to hang him twice because the rope broke the first time. Once he was dead, his body was coated in pitch and stuffed into the gibbet — an iron cage that had been made to order to fit him — to serve as warning to all who would follow in his footsteps.

Thanks to modern technology and the Museum of London, the Captain lives again. You can now follow William Kidd’s adventures on Twitter.