London’s Wellcome Collection has a fascinating collection of charms and amulets on display. The amulets were collected by amateur folklorist Edward Lovett (1852–1943) who had a particular interest in superstitions. Over the years he accumulated 1,400 beautiful, odd, creepy pieces which he first displayed in an exhibition at the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum in 1916. Most of the collection belongs to Oxford University’s Pitt Rivers Museum now but has been loaned to the Wellcome again almost a hundred years later.

Lovett was a cashier at a London bank who lived in Croydon. His real passion, though, was collecting objects people carried for good luck. He would roam the East End slums and docks of London at night looking for interesting specimens to buy off of sailors and hawkers. Because people came from all over the world to London’s docks, he ended up amassing an enormous quantity and variety of charms, so many that his wife walked out on him in 1925.

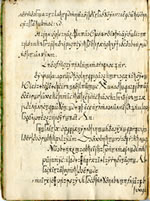

He wrote a book that year, Magic in Modern London, about his research and collection. He wasn’t an assiduous labeler, I’m afraid, so many of the 1,400 objects have no information about their context — where he got them, from whom, what their magical properties were — which makes the descriptions in the book invaluable.

There’s a selection of some of the most intriguing pieces in the Wellcome’s online gallery, along with some quotes from Magic in Modern London. I was surprised at how few of the charms I recognized as superstitions I’ve personally encountered (or engaged in). Red coral, the number 13, horseshoes, rice at weddings and wishbones are the only ones in the gallery I’m familiar with, and they’re not even the most interesting ones.

How would you like to carry two mole’s feet to keep you safe from the agony of cramps?

“The front feet of a mole are permanently curved for digging, and this curved appearance is so suggestive of cramp that these feet are carried as a cure for cramp.” Edward Lovett, Magic in Modern London, p. 78

Perhaps the lower jaw of an indeterminate small critter with a silver-mounted chain instead?

My favorite, though, looks fresh from the set of Nine Inch Nails’ “Closer” video (NSFW):

“A cow keeper, who was one of the old school and originally came from Devonshire, had the misfortune to incur the intense wrath of a man of vindictive temper. He threatened to bewitch the poor man’s cows, and two of then died. The cow keeper there upon, took the heart of one of the dead animals, stuck it all over with pins and nails and hung it up in the Chimney of his house… such action is supposed to be of such a serious nature that it brought about an arrangement of a more or less satisfactory character.” Edward Lovett, Magic in Modern London, p. 67

I’m impressed by how individual these practices were. Lovett said in his book that many times the owners of the talismans would assure him they weren’t superstitious at all; it’s just that x object genuinely saved their lives this one time. Lovett wasn’t the best at cataloging and documentation, but he was able to collect arresting physical representations of the immense variety of beliefs. His contemporaries recognized that he was doing something special, even new, by studying contemporary folklore.