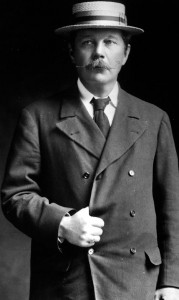

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, back before he was a sir, was a physician struggling to build a private practice. He supplemented his meager income, as he had while a medical student at the University of Edinburgh, by writing short stories that were published in magazines. His first short story to make it into print, The Mystery of the Sasassa Valley, was published in the Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal in 1879.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, back before he was a sir, was a physician struggling to build a private practice. He supplemented his meager income, as he had while a medical student at the University of Edinburgh, by writing short stories that were published in magazines. His first short story to make it into print, The Mystery of the Sasassa Valley, was published in the Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal in 1879.

There wasn’t much money to be made selling stories to magazines, however, and the common practice at the time was to publish content anonymously. He would later note in an 1893 article in The Idler magazine that over his years of writing short stories, he earned an average of less than 50 pounds a year from his work and he was still a complete unknown. Conan Doyle realized that if he wanted to make a name for himself as an author, he would have to write a novel. Sometime between 1883 and 1884, he did so and mailed the manuscript to a publisher. Then disaster struck.

Alack and alas for the dreadful thing that happened! The publishers never received it, the post office sent countless blue forms to say that they knew nothing about it, and from that day to this no word has ever been heard of it. Of course it was the best thing I ever wrote. Who ever lost a manuscript that wasn’t? But I must in all honesty confess that my shock at its disappearance would be as nothing to my horror if it were suddenly to appear again—in print. If one or two other of my earlier efforts had also been lost in the post my conscience would have been the lighter. This one was called “The Narrative of John Smith,” and it was of a personal-social-political complexion. Had it appeared I should have probably awakened to find myself infamous, for it steered, as I remember it, perilously near to the libellous. However, it was safely lost, and that was the end of another of my first books.

Psych, Conan Doyle! You only thought it was safely lost! Really, though, he pysched himself out because the original manuscript never did turn up; he just rewrote the whole thing from memory but only told his mother so nobody realized it. He made no reference to it in his 1924 autobiography and subsequent biographers assumed that the first novel was lost for good. It wasn’t until 1970 when Arthur’s youngest son Adrian Conan Doyle died and his wife had an expert examine the huge collection of Conan Doyle’s papers Adrian had left her that a group of four notebooks containing an unpublished, untitled novel were noticed.

Psych, Conan Doyle! You only thought it was safely lost! Really, though, he pysched himself out because the original manuscript never did turn up; he just rewrote the whole thing from memory but only told his mother so nobody realized it. He made no reference to it in his 1924 autobiography and subsequent biographers assumed that the first novel was lost for good. It wasn’t until 1970 when Arthur’s youngest son Adrian Conan Doyle died and his wife had an expert examine the huge collection of Conan Doyle’s papers Adrian had left her that a group of four notebooks containing an unpublished, untitled novel were noticed.

The notebooks still weren’t identified as The Narrative of John Smith at that point. They remained in the Conan Doyle archive and no scholars paid them any mind. The title was only associated with the rewritten manuscript in 2004, when the heirs of Anna Conan Doyle, Adrian’s wife, decided to sell the collection of Conan Doyle papers at a Christie’s auction. The Christie’s experts identified the four notebooks in Lot 11 as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s lost first novel, The Narrative of John Smith.

The narrator ranges widely over the fields of history, religion, philosophy, medicine, science, music and prophecy; he advances views on domestic interiors, art, the future of China, the United States and Great Britain and he draws on his experiences from sealing in the Arctic, to ballooning and to travel in South Africa. He also refers to literature citing the stories of Bret Harte and Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons.

It is evident that Conan Doyle began to revise the text of the first volume (changing the name of the doctor from Julep to Turner, for instance, and making other alterations). Mrs Rundle was a precursor of Sherlock Holmes’s housekeeper Martha Hudson.

The British Library bought the manuscript for £47,800 ($84,749) to add to their already extensive Conan Doyle collection. Sir Arthur’s daughter, Dame Jean Conan Doyle, had left 900 documents to the library in her will. In addition to the notebooks, the British Library purchased 1,200 other Conan Doyle documents from the Anna Conan Doyle auction.

Until now, few people had had the opportunity to see the dawn of Conan Doyle as a novelist. The British Library has transcribed the manuscript and published The Narrative of John Smith.

Until now, few people had had the opportunity to see the dawn of Conan Doyle as a novelist. The British Library has transcribed the manuscript and published The Narrative of John Smith.

An introduction to the new edition says: “The Narrative is not successful fiction, but offers remarkable insight into the thinking and views of a raw young writer who would shortly create one of literature’s most famous and durable characters, Sherlock Holmes.” The book gives a flavour of the preoccupations of the time, such as the British empire, science and the rise of secularism. It is also remarkably prescient, foreseeing the rise of America and China as superpowers, the advent of aeroplanes and submarines, and even space exploration. Stephen Fry, who has also seen the book, hailed Conan Doyle’s breadth of interests. “He was the first popular writer to tell the wider reading public about narcotics, the Ku Klux Klan, the mafia, the Mormons, American crime gangs, corrupt union bosses and much else besides. His boundless energy, enthusiasm and wide-ranging mind, not to mention the perfect, muscular and memorable prose, are all on display here in a work whose publication is very, very welcome indeed.”

You can purchase a copy now from the British Library bookshop or pre-order it on Amazon US (the scheduled publication date is October 15). If you’re fortunate enough to be in London over the next few months, you can see the manuscript with your own eyes at the British Library’s exhibit dedicated to Conan Doyle’s early travails as a writer.

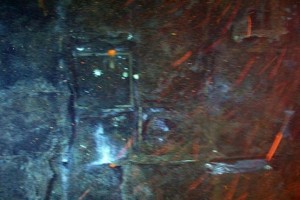

Archaeologists studying the 13,000-year-old cave art in the Cave of a Hundred Mammoths in Rouffignac, France, have discovered that some of the designs were painted by children. One particular area of the cave is replete with finger painted lines in a variety of geometric shapes called finger fluting that were made by children. Researchers have identified the marks of four children between two and seven and four adults working in this chamber.

Archaeologists studying the 13,000-year-old cave art in the Cave of a Hundred Mammoths in Rouffignac, France, have discovered that some of the designs were painted by children. One particular area of the cave is replete with finger painted lines in a variety of geometric shapes called finger fluting that were made by children. Researchers have identified the marks of four children between two and seven and four adults working in this chamber.