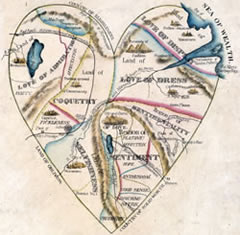

I’m afraid it’s not terribly flattering. Coquetry, Selfishness, Love of Admiration, Love of Display and Love of Dress take up more than three quarters of the treacherous terrain that is a woman’s heart. Even in the Country of Solid Worth, encircled by the intimidating barrier of the Ego Mountains, the more serene territories of Hope, Enthusiasm and Platonic Affection are transected by the River of Lasciviousness.

I’m afraid it’s not terribly flattering. Coquetry, Selfishness, Love of Admiration, Love of Display and Love of Dress take up more than three quarters of the treacherous terrain that is a woman’s heart. Even in the Country of Solid Worth, encircled by the intimidating barrier of the Ego Mountains, the more serene territories of Hope, Enthusiasm and Platonic Affection are transected by the River of Lasciviousness.

It was published by D.W. Kellogg & Co. of Hartford, Connecticut, between 1833 and 1842. “The Open Country of Woman’s Heart” lithograph, subtitled “Exhibiting its internal communications, and the facilities and dangers to Travellers therein,” claims to have been created by “A Lady” but I don’t know if that’s true because I don’t see the Gigantic Sinkhole of Self-Loathing anywhere on the map. On the other hand, then as is now, there were plenty of women who held a low opinion of their gender’s innate failings so who knows?

The map is part of a fascinating online exhibit by the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts, called “Beauty, Virtue and Vice: Images of Women in Nineteenth-Century American Prints.” Using their extensive collection of images from the colonial period through the Civil War and Reconstruction, the AAS give us a glimpse into the iconography of the 19th century and what it tells us about popular views of women in society, particularly the views of middle-to-upper class New England from whence many of the sources spring.

The exhibit connects this map to the Cult of True Womanhood, aka the Cult of Domesticity, as described in “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820–1860,” (pdf) an influential 1966 paper by historian Barbara Welter. The “True Woman” of the 19th century was characterized by the four cardinal virtues of piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity. These were the divinely ordained provinces of the woman. Anything outside of that, from political activism to just having a job, could only lead women to a life of restlessness and unhappiness. Without her cardinal virtues to protect her, the woman is too easily debauched by the predations of ever-lustful men.

I’m not sure if the connection between map and True Womanhood is clear, however. The idea that women are inherently pure (albeit weak and temptation-prone, of course) and thus fulfilled only as mothers, wives, paragons of domesticity, doesn’t quite jibe with the vain, narcissistic, gold-digger depicted in the map. It reads more like the work of a penniless artist who got dumped for a rich dude to me.

Nonetheless, the exhibit is very much worth a read, as is the rest of the AAS website. I always appreciate when a museum or library makes an effort to give Internet viewers access to their collections, complete with nice big scans. That they’ve used their primary sources to create online exhibitions around a coherent theme makes it all the more readable and enjoyable. Next on my perusal list are Architectural Resources at the American Antiquarian Society and An Invitation to Dance: A History of Social Dance in America.