Scientists from the Universities of Liverpool and Manchester have published a new study in the journal Biology Letters estimating that the bite force of Tyrannosaurus rex ranged between 35,000 and 57,000 newtons, or 7,868 and 12,814 pounds of pressure. That’s the equivalent of a medium-sized elephant sitting on you and it’s the strongest bite of any land animal to ever tread our green earth. It’s also almost 20 times more powerful than previous estimates of T. rex’s bite.

Scientists from the Universities of Liverpool and Manchester have published a new study in the journal Biology Letters estimating that the bite force of Tyrannosaurus rex ranged between 35,000 and 57,000 newtons, or 7,868 and 12,814 pounds of pressure. That’s the equivalent of a medium-sized elephant sitting on you and it’s the strongest bite of any land animal to ever tread our green earth. It’s also almost 20 times more powerful than previous estimates of T. rex’s bite.

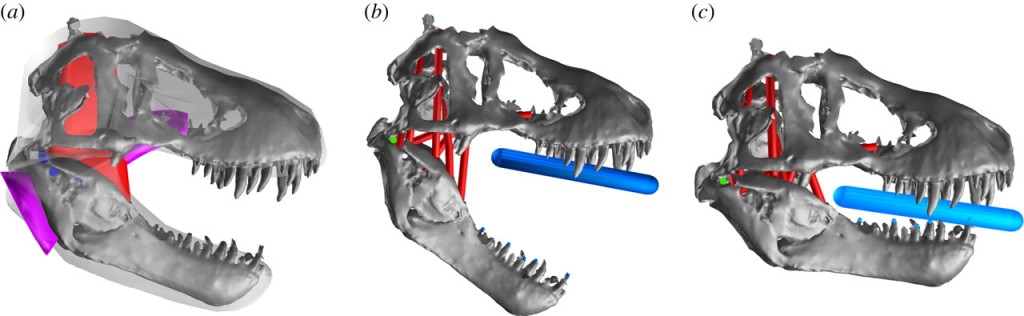

Using laser scanners, researchers digitized the full-scale copy of the skull of an adult T. rex that was on display at Manchester Museum. The resulting 3D model of the T. rex skull was the basis for the bite model. Since muscles and joints don’t fossilize, scientists used computer modeling to reconstruct the muscular and joint structure of the T. rex’s jaw. They based the reconstruction on the muscular structures of modern crocodiles and birds, both of whom share a common ancestor with dinosaurs.

They then mapped the muscles and joints onto the skull model and made the muscles contract to their fullest extent, like the T. rex was snapping its jaws shut. The researchers measured the force when the model’s teeth hit each other. The strongest bite force was at the back of the teeth — between 30,000 and 60,000 Newtons — just as with humans who can bite harder with their molars than with their front teeth.

When they used their methodology to calculate the bite force of living animals, their results were within 5 to 20% of the actual range. They included that accuracy range in their calculation of the T. rex biting force.

(a) Multi-body dynamic analysis (MDA) 3D digitized T. rex skull with reconstructed soft tissues (red, adductor mandibulae externus group; blue, adductor mandibulae posterior group; purple, pterygoideus group). (b) MDA model with joints (green), muscles (red cylinders), and ‘contact’ springs (blue spheres and cylinder) in starting bite pose. (c) MDA model during sustained biting.

Using this model, the researchers found a surprising difference between young T. rex and mature ones: the power of the bite increased disproportionately with maturity. It’s not a linear increase in bite force based solely on the size differential between adults and youths. This might mean that an adult T. rex had a significantly different diet and fighting style than it did when it was growing up.

Earlier studies calculated T. rex’s maximum bite force at a modest 8,000-13,000 Newtons. According to University of Liverpool’s Dr. Karl Bates, those studies were kneecapped because they extrapolated data from much smaller animals — none larger than 450 pounds, while the T. rex was 15,000 pounds — or because they were calculated from fossilized T. rex bite marks and there’s no way of knowing how hard the animal was biting when it left the mark that would turn to stone.

They weren’t the strongest biters ever. In all likelihood, that honor goes to Megalodon, the prehistoric shark which certainly has the jaws for it. We have even less to go on with Megalodon than we do with T. rex, because the only fossilized remains we have of the ancient shark are its teeth. We don’t even have its jaw bones. The study that estimated its biting power at 24,000 to 40,000 pounds used computer models of a great white shark’s jaws and then multiplied the results by Megalodon’s size and weight. However, Megalodon was not just a much larger great white — it’s not even a direct ancestor — so there’s no reason to assume its bite was similar enough to be able to extrapolate force from one animal to the other.