Archaeologists working on the undercroft of York Minster, the 13th century Gothic cathedral that is the largest medieval cathedral north of the Alps, have found human remains that in all likelihood predate the current building. The site has had a church on it since at least the 7th century A.D., but fires, Danes and Normans damaged and destroyed the previous structures. The current iteration took 250 years to build starting in 1220. Since this burial was entirely undisturbed, archaeologists think it took place before the Gothic minster was built around it.

Archaeologists working on the undercroft of York Minster, the 13th century Gothic cathedral that is the largest medieval cathedral north of the Alps, have found human remains that in all likelihood predate the current building. The site has had a church on it since at least the 7th century A.D., but fires, Danes and Normans damaged and destroyed the previous structures. The current iteration took 250 years to build starting in 1220. Since this burial was entirely undisturbed, archaeologists think it took place before the Gothic minster was built around it.

The Very Reverend Keith Jones, Dean of York, said: “York Minster’s walls have been witness to centuries of human life and I feel sure that archaeologists are likely to encounter even more human burials during their three-week tenure: we would expect to find, when working at York Minster, evidence of previous life all around the place.

“Having found the remains of our forebears, they will be reverently cared for until such time as they can be reinterred with the walls of York Minster.”

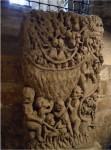

The bones might even date to the 12th century when the Norman cathedral was still standing. The undercroft, the vaulted cellar below ground level, has archaeological remains covering all of York’s history, from the Roman fort to the Norman foundations. There’s an exhibit of artifacts on display in the undercroft normally, including a luscious Norman-era 12th century relief of sinners being tortured by demons in Hell’s cauldron felicitously known as the Doomstone, but the undercroft was closed to the public as of January this year and will remain so until March 2013. Visitors are allowed to view the archaeologists at work, though.

The bones might even date to the 12th century when the Norman cathedral was still standing. The undercroft, the vaulted cellar below ground level, has archaeological remains covering all of York’s history, from the Roman fort to the Norman foundations. There’s an exhibit of artifacts on display in the undercroft normally, including a luscious Norman-era 12th century relief of sinners being tortured by demons in Hell’s cauldron felicitously known as the Doomstone, but the undercroft was closed to the public as of January this year and will remain so until March 2013. Visitors are allowed to view the archaeologists at work, though.

The closure is part of an ambitious £10.5 million renovation program called York Minster Revealed which, among other priorities, will install wheelchair accessible lifts and ramps in front of and inside the church. For the first time in 40 years, archaeologists were allowed to excavate inside the building in order to prepare for the lift installation. The last time archaeologists got to poke around inside was 1972 when severe structural problems threatened the central tower with collapse. That was when they found the Roman and Norman remains in the undercroft.

The closure is part of an ambitious £10.5 million renovation program called York Minster Revealed which, among other priorities, will install wheelchair accessible lifts and ramps in front of and inside the church. For the first time in 40 years, archaeologists were allowed to excavate inside the building in order to prepare for the lift installation. The last time archaeologists got to poke around inside was 1972 when severe structural problems threatened the central tower with collapse. That was when they found the Roman and Norman remains in the undercroft.

In addition to the updating of the amenities for visitors to the church, York Minster Revealed also focuses on developing the rare and precious ancient crafts of stonemasonry and stained glass conservation. York Minster’s Great East Window is one of the world’s largest medieval stained glass windows, and both the masonry in which it’s embedded (it’s buckling) and the glass (darkened by dirt and soot) are in dire need of conservation.

In addition to the updating of the amenities for visitors to the church, York Minster Revealed also focuses on developing the rare and precious ancient crafts of stonemasonry and stained glass conservation. York Minster’s Great East Window is one of the world’s largest medieval stained glass windows, and both the masonry in which it’s embedded (it’s buckling) and the glass (darkened by dirt and soot) are in dire need of conservation.

York Minster is one of the few remaining churches to have its own in-house stone yard where craftsmen learn to carve stone using the same techniques and materials their 13th century forebears used. Visitors to the cathedral will be able to attend workshops where they will see the stone masons and glaziers at work and have the opportunity to talk to the craftsmen about the restoration.

All of the masonry is in regular need of replacement, so much so that the minster holds an annual stone auction where stonework that has been removed and replaced with a modern copy is sold to the general public and the profits used to fund further restorations. Prices start at about £30 a block which is a steal for moss-covered, carved 800-year-old limestone. The minster keeps archaeologically significant pieces, of course.

All of the masonry is in regular need of replacement, so much so that the minster holds an annual stone auction where stonework that has been removed and replaced with a modern copy is sold to the general public and the profits used to fund further restorations. Prices start at about £30 a block which is a steal for moss-covered, carved 800-year-old limestone. The minster keeps archaeologically significant pieces, of course.