In a rare instance of a court ruling in the interests of justice rather than on the precise merits of the law, Germany’s top federal appeals court has decided that the German Historical Museum must return a collection of 4,529 rare late 19th, early 20th century posters to Peter Sachs, the son of the original collector.

In a rare instance of a court ruling in the interests of justice rather than on the precise merits of the law, Germany’s top federal appeals court has decided that the German Historical Museum must return a collection of 4,529 rare late 19th, early 20th century posters to Peter Sachs, the son of the original collector.

Hans Josef Sachs’ lifelong passion for graphic art began when he was a teenager in the late 1890s. His roommate at the Breslau Gymnasium had posters plastered all over the walls and Hans was enchanted. The early focus of his collection was Parisian posters designed by the likes of Art Nouveau master Alphonse Mucha. As German artists in Berlin and Munich began to modernize the form, Sachs’ collection embraced them. His taste was impeccable. Posters in his collection advertised food, movies, theatrical performances, political propaganda, museum exhibitions, every one of them rare, printed in very small original runs.

By the time he was 24 years old in 1905, he had the largest private collection of posters in Germany. That year, he and five other poster lovers founded the Verein der Plakat Freunde (the Society for Friends of the Poster). In 1910, Hans founded Das Plakat (“The Poster”), a journal about posters which is considered a highly influential watershed in the history of graphic art. (See some of the amazingly gorgeous cover art on this blog.) The society and journal gave him access to even more posters for his collection. He ran the magazine, writing much of its copy, until it folded in 1921.

By the time he was 24 years old in 1905, he had the largest private collection of posters in Germany. That year, he and five other poster lovers founded the Verein der Plakat Freunde (the Society for Friends of the Poster). In 1910, Hans founded Das Plakat (“The Poster”), a journal about posters which is considered a highly influential watershed in the history of graphic art. (See some of the amazingly gorgeous cover art on this blog.) The society and journal gave him access to even more posters for his collection. He ran the magazine, writing much of its copy, until it folded in 1921.

After an attic fire that threatened but thankfully did not damage his collection, Sachs began to work on finding a way to display the posters so that the public could see them. In 1926 he had an addition built to house his collection. He dubbed it the Museum of Applied Arts and opened it to the public.

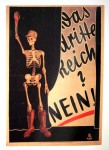

A dentist by profession, Sachs continued to practice until 1935 when his Jewish heritage ran afoul of the Nuremberg Laws. To protect his collection, he transferred technical ownership of it to banker Richard Lenz who was not Jewish. In the summer of 1938, before Lenz could take possession, Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels confiscated the entire collection, which had grown to an astounding 12,500 individual pieces. He wanted to install the collection — doubtless purged of all modernism — in a museum of his own.

On November 9, 1938, Hans Sachs was arrested during Kristallnacht and sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp outside of Berlin. He was released 20 days later and wasted no time collecting his wife Felicia and his one-year-old son Peter and getting the hell out of Germany. They fled to London and thence to New York.

On November 9, 1938, Hans Sachs was arrested during Kristallnacht and sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp outside of Berlin. He was released 20 days later and wasted no time collecting his wife Felicia and his one-year-old son Peter and getting the hell out of Germany. They fled to London and thence to New York.

After the war was over, Hans assumed the collection had been destroyed, so he applied for reparations under the Federal Republic of Germany’s refund policy. In March 1961, the West German government paid him about $50,000 (225,000 German marks) as compensation for his loss. It seems a small amount now, but at the time it was a generous offer that everyone advised Hans accept. He did.

In 1966, Sachs discovered that about 8,000 posters from his collection had survived the war and were in an East Berlin museum. He wrote to the East German authorities not even asking for the posters back, but just offering to meet museum officials to offer his expertise. He also wanted to ascertain if the collection were on public display. The East German government replied to him in July of 1966 rejecting his offer because discriminatory West German legislation made collaboration between their experts impossible.

Hans Josef Sachs died in 1974 never having laid eyes on his collection again. After the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, the poster collection, now mysteriously reduced to fewer than 5,000 pieces, was transferred to the German Historical Museum in Berlin where it remained mainly in storage, with just a handful of posters on display at any given time.

Hans Josef Sachs died in 1974 never having laid eyes on his collection again. After the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, the poster collection, now mysteriously reduced to fewer than 5,000 pieces, was transferred to the German Historical Museum in Berlin where it remained mainly in storage, with just a handful of posters on display at any given time.

Hans’ son Peter had no idea the collection still existed until 2005. As soon as he found out, he tried to get it back. He offered to repay the 1961 compensation at their 2005 value of 600,000 euros, but the estimated market value of the posters had skyrocketed well into the millions (it’s assessed at $6 – $21 million now), and the museum did not want to lose such an irreplaceable and important collection. He took the case before the Advisory Committee for the Return of Nazi-confiscated Art in 2007, but since the government had paid reparations, the letter of the law was not on his side.

Peter Sachs took the case to district court, but in 2009 they agreed with the decision of the Advisory Committee. He kept appealing to higher courts, and now the Federal Court of Justice has ruled that Peter Sachs is the rightful owner of his father’s poster collection. The decision notes that although Peter did not file for restitution by the deadline and although his father had received legal compensation, for the posters not to be returned “would perpetuate Nazi injustice.” Since the intent of restitution laws was to reinstate the property rights stripped from the victims of Nazi terror, keeping the posters would contravene the entire point of the law.

Peter Sachs took the case to district court, but in 2009 they agreed with the decision of the Advisory Committee. He kept appealing to higher courts, and now the Federal Court of Justice has ruled that Peter Sachs is the rightful owner of his father’s poster collection. The decision notes that although Peter did not file for restitution by the deadline and although his father had received legal compensation, for the posters not to be returned “would perpetuate Nazi injustice.” Since the intent of restitution laws was to reinstate the property rights stripped from the victims of Nazi terror, keeping the posters would contravene the entire point of the law.

The museum has accepted the ruling with good grace, even though they’re bummed because the collection is of course a huge resource for scholars. Peter Sachs, now 74 years old, wants to fulfill his father’s dream of seeing the posters on public display, so his top priority is to find a museum where the entire collection can be showcased in all its glory.