In 1905, just four years after the city of Fairbanks, Alaska was founded as a trading post by riverboat captain, price-gouger, embezzler and convicted swindler E.T. Barnette, the First National Bank of Fairbanks released the first national bank notes in Alaska from the US Treasury into circulation. Alaska wasn’t even a Territory at this time. It was a District, like a very large, very cold Washington, D.C., governed by federal appointees since 1884. Before that it had been under the control of the military. It wouldn’t be made a Territory until 1912.

The discovery of gold in the neighboring Klondike region of Canada’s Yukon Territory in 1896 swelled the population of Alaska with prospectors and all the commerce that grows around them. It also made an old boundary dispute between the United States and Canada suddenly become a matter of intense urgency. The dispute was inherited from the days when Alaska was Russian. The terms of the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1825 were vague and although Canada had asked the United States for a survey to resolve the issues back in 1872, the US refused, deeming it too expensive. One the Gold Rush began in 1897, it was too expensive not to decide once and for all the precise eastern boundary of Alaska and whether the entire panhandle, with its invaluable access to Pacific ports, should be United States territory or whether at least some fjords were Canadian. Canada in particular claimed the head of Lynn Canal, which would give them direct access to shipping from the Yukon gold fields.

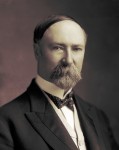

In 1898, the United States and Great Britain created a Joint High Commission to adjudicate the boundary dispute. Representatives from both countries met in Quebec City on August 23. One of the US delegates was Charles W. Fairbanks, at that time the Republican United States Senator from Indiana who six years later would become Vice President of the United States under President Theodore Roosevelt. The commission came close to reaching a compromise, but in 1899 the government of British Columbia rejected it. The boundary dispute would not be resolved until a 1903 arbitration tribunal in which the British representative sided with the US over Canada, ultimately resulting in a thaw of US-Canada relations and a frigid pall cast over Canada’s with Britain.

In 1898, the United States and Great Britain created a Joint High Commission to adjudicate the boundary dispute. Representatives from both countries met in Quebec City on August 23. One of the US delegates was Charles W. Fairbanks, at that time the Republican United States Senator from Indiana who six years later would become Vice President of the United States under President Theodore Roosevelt. The commission came close to reaching a compromise, but in 1899 the government of British Columbia rejected it. The boundary dispute would not be resolved until a 1903 arbitration tribunal in which the British representative sided with the US over Canada, ultimately resulting in a thaw of US-Canada relations and a frigid pall cast over Canada’s with Britain.

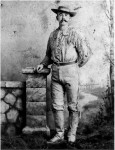

During the dispute, Charles Fairbanks met James Wickersham, a judge and Washington state representative. Fairbanks became a political patron of his. He worked to secure a federal judgeship for Wickersham in the brand new Third Judicial District covering Alaska in 1900. Wickersham wanted the job and had lobbied for it actively, so he was deeply grateful to Fairbanks for his help. He was packed and on his way to Nome in June of 1900.

His new district was 300,000 square miles in area with no paved roads. Transportation was primarily riverboat and dogsled-based, and settlements weren’t even legally allowed to incorporate into cities until that year. There was also very little in the way of US currency, and what there was of it was carried in from the lower 48.

His new district was 300,000 square miles in area with no paved roads. Transportation was primarily riverboat and dogsled-based, and settlements weren’t even legally allowed to incorporate into cities until that year. There was also very little in the way of US currency, and what there was of it was carried in from the lower 48.

In July of 1902, Judge Wickersham traveled to St. Michael, a trading settlement on the west coast of Alaska, as part of his judicial duties. E.T. Barnette was in town putting together a steamer he had bought in Seattle earlier in the year that was shipped to St. Michael in pieces. The two men met and struck up a conversation. Barnette told him about the trading post he had set up on the south bank of the Chena River the year before when his transport steamer ran aground on the way to the Tanana River Crossing. He planned to use the new steamer, the Isabelle, to take him and his cargo the rest of the way.

Wickersham was impressed with Barnette’s plan and told him that he should name his new Tanana Crossing trading post Fairbanks after the Indiana Senator. The judge told him that if he did, he would do his utmost to move the district headquarters from Eagle to the newly named town. Barnette, ever ambitious, liked the idea because if they ever needed a hand from Washington, it would be good to have someone with influence on their side.

Wickersham was impressed with Barnette’s plan and told him that he should name his new Tanana Crossing trading post Fairbanks after the Indiana Senator. The judge told him that if he did, he would do his utmost to move the district headquarters from Eagle to the newly named town. Barnette, ever ambitious, liked the idea because if they ever needed a hand from Washington, it would be good to have someone with influence on their side.

By the time Barnette made it back to Chenoa City, he found his accidental trading post was suddenly prime real estate. An Italian prospector named Felice Pedroni (aka Felix Pedro), who had purchased much of his stock the year before when he was stranded on the riverbank, had found the major gold vein he had been looking for. Barnette abandoned his plan to move to the Tanana Crossing and instead staked some local claims and started making something permanent out of his post.

By the time Barnette made it back to Chenoa City, he found his accidental trading post was suddenly prime real estate. An Italian prospector named Felice Pedroni (aka Felix Pedro), who had purchased much of his stock the year before when he was stranded on the riverbank, had found the major gold vein he had been looking for. Barnette abandoned his plan to move to the Tanana Crossing and instead staked some local claims and started making something permanent out of his post.

As word of the gold find spread around Alaska, people started pouring into the new town. The papers got wind of it in January, 1903, and the next gold rush was on. Barnette persuaded the settlers to rename the town Fairbanks. Judge Wickersham came to visit in April. He was not impressed with the handful of log cabins and tents, but he got a great deal on a piece of land courtesy of Barnette’s brother-in-law and also got two streets named after US Representatives.

The city was incorporated on November 10th, 1903, and on November 11th, despite having lost the election to John Long by five votes, Barnette strong-armed the city council into swearing him in as Fairbanks’ first mayor. In 1904, Wickersham followed through making Fairbanks the new headquarters of the Third Judicial District. He started the first newspaper in town that he typed himself. That November, Charles Fairbanks became Vice President of the United States. Gold production increased from $40,000 the year before to $600,000.

The city was incorporated on November 10th, 1903, and on November 11th, despite having lost the election to John Long by five votes, Barnette strong-armed the city council into swearing him in as Fairbanks’ first mayor. In 1904, Wickersham followed through making Fairbanks the new headquarters of the Third Judicial District. He started the first newspaper in town that he typed himself. That November, Charles Fairbanks became Vice President of the United States. Gold production increased from $40,000 the year before to $600,000.

Fairbanks’ roll continued the next year. The city got a bridge, a hospital, a church, a local train and a bank. The First National Bank of Fairbanks was founded by Samuel A. Bonnifield, a famed Klondike gambler and casino owner known as “Square Sam” or “Silent Sam” for his reputed quiet, honest demeanor. The city was awash in gold — production would total $6 million that year — and the ever-expanding population needed currency. The First National Bank deposited money with the US Treasury and got thousands of sheets of $5, $10 and $20 bank notes to circulate.

The bank saved the third $5 bill from the first sheet for a very special recipient: Charles W. Fairbanks. They framed the bank note and presented it to the Vice President. The bill was handed down in the Fairbanks family to the current owner, great-grandson Charles Fairbanks IV, who kept it on his wall for years. Its estimated value in the 1990s was $50,000 to $60,000, which was nerve-wracking enough, but when he found out last year that its market value had at least quadrupled, he took it off the wall and put it in a safe deposit box.

The bank saved the third $5 bill from the first sheet for a very special recipient: Charles W. Fairbanks. They framed the bank note and presented it to the Vice President. The bill was handed down in the Fairbanks family to the current owner, great-grandson Charles Fairbanks IV, who kept it on his wall for years. Its estimated value in the 1990s was $50,000 to $60,000, which was nerve-wracking enough, but when he found out last year that its market value had at least quadrupled, he took it off the wall and put it in a safe deposit box.

Now he has decided to take it out of the bank and put it up for auction at Heritage Auctions in Dallas. The pre-sale estimate is $200,000 to $300,000 with a starting bid of $120,000.

Now he has decided to take it out of the bank and put it up for auction at Heritage Auctions in Dallas. The pre-sale estimate is $200,000 to $300,000 with a starting bid of $120,000.

As for the eccentric heroes of our story, both Barnette and Bonnifield wound up mired in fiscal shenanigans. Bonnifield got in trouble for attempting to evade banking regulations by setting up dummy banks. In 1909, all of the bank’s stock was sold to Barnette. Bonnifield had a nervous breakdown and left town, heading back home to Kansas to recover. He returned to Fairbanks in August of 1910 and was welcomed by the community who still held him in high esteem. In October of 1911, he withdrew a large sum of money from the bank, distributed some of it to laborers in town, then took the rest to the riverbank and played with it in the sand. A few days later he was arrested for insanity, found guilty and sent to Morningside Hospital in Portland, Oregon. He was released in 1914 and eventually died in Seattle at the age of 77.

Barnette purchased the Washington-Alaska Bank and the First National Bank of Fairbanks in 1909. He folded his own banking concern in with the other two under the Washington-Alaska name. Two years later, the Washington-Alaska Bank went bankrupt, leaving Fairbanks residents $1 million poorer. Barnette took $500,000 and slipped out of town. He was arrested for embezzling, but the trial was a farce and he was let off with slap on the wrist. He moved to Los Angeles, got involved with another woman, got dumped by his wife, and then moved to Mexico where he lived out the rest of his days in grand style.

Wickersham continued to serve as district judge until 1908, after which he successfully ran to be the sole representative of the District of Alaska to Congress. In 1912 the District became the Territory and Wickersham pressed for legislation allowing home rule. He got it. He was also instrumental in the creation of Mt. McKinley National Park and got the Alaska Railroad built in 1914 after giving a 5 1/2 hour speech on the floor of Congress. He submitted the first bill for Alaskan statehood in 1917. It didn’t pass, but he never stopped advocating for it.

He remained the representative from Alaska until 1921. He practiced law for a spell in Juneau, was elected to Congress again in 1931, and then went back to his Juneau practice. He published his memoirs, Old Yukon, in 1938, which have recently been republished. He died in Juneau, Alaska on October 24, 1939.