Three panels of the huge and breathtakingly beautiful 4th century A.D. Roman mosaic unearthed in Lod, Israel, in 1996, is now on display at Penn Museum in Philadelphia, the last chance for US audiences to see the masterpiece before it leaves the country. The mosaic began its tour of the US in New York City in 2010. Since then it’s been to San Francisco, Chicago, and Columbus, Ohio. After the Penn exhibit closes on May 12th, the mosaic panels will travel to the Louvre in Paris until August 19th, and then they go home to be reunited with the rest of the work.

Three panels of the huge and breathtakingly beautiful 4th century A.D. Roman mosaic unearthed in Lod, Israel, in 1996, is now on display at Penn Museum in Philadelphia, the last chance for US audiences to see the masterpiece before it leaves the country. The mosaic began its tour of the US in New York City in 2010. Since then it’s been to San Francisco, Chicago, and Columbus, Ohio. After the Penn exhibit closes on May 12th, the mosaic panels will travel to the Louvre in Paris until August 19th, and then they go home to be reunited with the rest of the work.

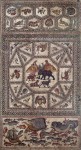

The panels on display fit together to form the largest, best-preserved and most intricate part of the 600-square-foot floor. The top panel features prey or food animals like birds, fish and game, some of them on their own, others shown in a deadly embrace with the lion, tiger, leopard and snake about to claim their lives. The middle panel has more of those animals in polyhedral frames with one large central tableau of exotic species in confrontational postures. An elephant takes on a giraffe and a rhinoceros while a tiger pulls on the tail of a … wildebeest? An aurochs? Some kind of horned animal. Behind them a lion and lioness stand proudly on mountains overlooking water and a sea monster. The bottom panel is a single scene populated with dolphins, shells, fish of many species and two merchant ships, one with spread sails full of wind, the other with lowered mast and sails. Elaborately braided geometric borders wind their way through and around each panel.

The panels on display fit together to form the largest, best-preserved and most intricate part of the 600-square-foot floor. The top panel features prey or food animals like birds, fish and game, some of them on their own, others shown in a deadly embrace with the lion, tiger, leopard and snake about to claim their lives. The middle panel has more of those animals in polyhedral frames with one large central tableau of exotic species in confrontational postures. An elephant takes on a giraffe and a rhinoceros while a tiger pulls on the tail of a … wildebeest? An aurochs? Some kind of horned animal. Behind them a lion and lioness stand proudly on mountains overlooking water and a sea monster. The bottom panel is a single scene populated with dolphins, shells, fish of many species and two merchant ships, one with spread sails full of wind, the other with lowered mast and sails. Elaborately braided geometric borders wind their way through and around each panel.

It’s one of the most complete and largest Roman mosaics ever discovered. Archaeologists estimate that it took three years to make the entire floor, a painstaking process requiring exact planning of the positions of every one of the two million tesserae. The north panels, the ones that are on display, were made by one great master, the south panel by another. A third panel between the two was made by a third master, not quite as skilled as the first two, and was probably installed last.

In all its vast complexity, there are no human figures or deities depicted, which is highly unusual for a work of this scope. Also unusual is the juxtaposition of hunting scenes and maritime activity. All we know about the context from the archaeological investigation is that the mosaics decorated several large rooms, probably a series of receptions or audience halls, in a private house. Pottery fragments and coins found above the floor date to the late 3rd and 4th centuries A.D., which places the likely date the mosaic was laid to around 300 A.D.

In all its vast complexity, there are no human figures or deities depicted, which is highly unusual for a work of this scope. Also unusual is the juxtaposition of hunting scenes and maritime activity. All we know about the context from the archaeological investigation is that the mosaics decorated several large rooms, probably a series of receptions or audience halls, in a private house. Pottery fragments and coins found above the floor date to the late 3rd and 4th centuries A.D., which places the likely date the mosaic was laid to around 300 A.D.

Nothing but the floor of the structure has survived, as far as we know. The collapse of the mud brick walls, which had once sported glorious frescoes in their own right, had the fortunate side-effect of preserving the floors. When the mosaic was first revealed during highway construction in 1996, emergency excavation unearthed a series of mosaic floors that measured a total of 50 by 27 feet. Funding was not available at that time to keep digging, so after a weekend of public display during which 30,000 people came to see the mosaic, the work was reburied until 2009 when a donation from the Shelby White and the Leon Levy Foundation allowed the Israel Antiquities Authority to re-excavate and conserve the mosaic. The  mosaic was peeled off the floor, revealing a fascinating collection of ancient footprints left in the mortar underneath the tesserae, but excavations continue and the complete floorplan of the villa has yet to be determined.

mosaic was peeled off the floor, revealing a fascinating collection of ancient footprints left in the mortar underneath the tesserae, but excavations continue and the complete floorplan of the villa has yet to be determined.

Originally known as Lydda, Lod was destroyed during the First Jewish War by Cestius Gallus, the Roman proconsul of Syria, on his way to Jerusalem in 66 A.D. Lydda was hit again during the Second Jewish War (115-117 A.D.) by Lusius Quietus. He besieged the town and when it fell, he executed much of its Jewish population. Shortly thereafter Hadrian renamed it Diospolis, city of gods, and the town’s population became increasingly Christianized. The town was elevated to official city status by Septimius Severus in 200 A.D., garnering it the unwieldy title of Colonia Lucia Septimia Severa Diospolis. Saint George of dragon fame was born there of Greek parents (there had been a strong Greek presence in Lydda since Alexander’s conquest in 333 B.C.) in the second half of the 3rd century. Whoever owned the home graced by the Lod mosaic in 300 A.D., he doubtless held high rank in the city, perhaps a Roman official, perhaps a prosperous merchant.

The entire floor mosaic, including the less elaborate, less pristine parts that remain in Israel, will go on display at the brand spanking new Shelby White and Leon Levy Lod Mosaic Archaeological Center which is scheduled to open in late 2014. The museum is being built around the archaeological site and the mosaic will be reinstalled exactly where it used to be for an in situ display with ongoing archaeological excavations visible to the public.

The entire floor mosaic, including the less elaborate, less pristine parts that remain in Israel, will go on display at the brand spanking new Shelby White and Leon Levy Lod Mosaic Archaeological Center which is scheduled to open in late 2014. The museum is being built around the archaeological site and the mosaic will be reinstalled exactly where it used to be for an in situ display with ongoing archaeological excavations visible to the public.

These videos are from a Metropolitan Museum of Art lecture series about the Lod Mosaic, exploring its archaeological context, the excavation, lifting (they cut it into 30 pieces and peeled them off the floor; it’s crazy), conservation and iconography. They’re 30 and 37 minutes long, but totally worth it. Watch them full screen because there are some excellent pictures of the excavation, the lifting, the fish painted on the floor to guide the placement of the tiles. It’s amazing, really.

[youtube=http://youtu.be/J8IW4y6xGUQ&w=430]

[youtube=http://youtu.be/CaqcSFc05-Q&w=430]