Traprain Law, a hill of volcanic rock in East Lothian, Scotland, looms ferociously over the surrounding plain making it an ideal location for a fort. Excavations have found evidence of dense settlement and defensive ramparts going back to 1000 B.C. In the first century A.D. it was occupied by a tribe the Romans called the Votadini (Gododdin in ancient British) who used it from about 40 A.D. certainly until about 400 A.D., with a short break around the end of the 2nd century when Romans went deeper into Scotland and built the Antonine Wall only to pull back to Hadrian’s Wall a few decades later.

Traprain Law, a hill of volcanic rock in East Lothian, Scotland, looms ferociously over the surrounding plain making it an ideal location for a fort. Excavations have found evidence of dense settlement and defensive ramparts going back to 1000 B.C. In the first century A.D. it was occupied by a tribe the Romans called the Votadini (Gododdin in ancient British) who used it from about 40 A.D. certainly until about 400 A.D., with a short break around the end of the 2nd century when Romans went deeper into Scotland and built the Antonine Wall only to pull back to Hadrian’s Wall a few decades later.

Some time around 410 to 425 A.D. or possibly even later, somebody buried a large quantity of Roman silver on Traprain Law. Fifteen centuries later, on May 12th, 1919, the hoard was unearthed on the western shelf of the hill by workmen excavating under the absentee direction of Alexander Curle, a lawyer who was also Director of the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland, and James Cree who was usually the hands-on supervisor but had the unfortunate timing to have been in the States during the 1919 dig season.

It was a massive find, weighing over 53 lbs composed of 250 fragments from about 150 objects of high quality silver in different styles and motifs that indicate they were manufactured in various workshops around the Roman Empire. There are a few complete pieces, but most of it is what is known as hacksilver, larger silver objects that have been cut into bits. Table silver — flasks, goblets, bowls, plates, spoons, ladles, serving dishes — make up the bulk of the hoard, with some objects from a lady’s dressing table, buckles and strap fittings from an officer’s uniform, early Christian items that may have been part of a church service or belonged to a wealthy Christian family, and four clipped coins from the emperors Valens (Eastern Roman emperor from 364 to 378), Arcadius (Eastern Roman emperor from 395 to 408) and Honorius (Western Roman emperor from 395 to 423).

It was a massive find, weighing over 53 lbs composed of 250 fragments from about 150 objects of high quality silver in different styles and motifs that indicate they were manufactured in various workshops around the Roman Empire. There are a few complete pieces, but most of it is what is known as hacksilver, larger silver objects that have been cut into bits. Table silver — flasks, goblets, bowls, plates, spoons, ladles, serving dishes — make up the bulk of the hoard, with some objects from a lady’s dressing table, buckles and strap fittings from an officer’s uniform, early Christian items that may have been part of a church service or belonged to a wealthy Christian family, and four clipped coins from the emperors Valens (Eastern Roman emperor from 364 to 378), Arcadius (Eastern Roman emperor from 395 to 408) and Honorius (Western Roman emperor from 395 to 423).

It’s largest hoard of Roman silver ever discovered outside the borders of the empire and the largest hoard of hacksilver ever found anywhere.

The initial assumption was that this silver was loot, the spoils of barbarian incursions into Britannia during or just after Rome’s departure. By this theory, the barbarians hacked up the artifacts after they pillaged them because, you know, barbarians. That’s not much of an explanation, though, and archaeological evidence uncovered at Traprain Law shows that the Votadini had a productive relationship with Rome. The settlement is littered with Roman artifacts like brooches, glass, pottery, tweezers and ear scoops that indicate regular trade and the influence of Roman culture over several centuries.

Recent research has suggested a more plausible explanation, that the hoard was payment for mercenary services rendered or a diplomatic gift to ensure the loyalty of a friendly chieftain. With currency hard to come by in the waning days of Roman Britain, cut up precious metal objects acted as bullion. By this theory, the objects were cut and flattened within Roman territory, measured, weighed and sent over the border. Some of the pieces were crushed into scale-sized packets weighing up to three-quarters of a Roman pound which fits nicely with the payment idea.

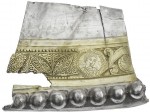

Two of the fragments are all that remains of a large silver dish decorated with a beaded rim and a geometric border with floral accents and portrait busts. The border is gilded and inlaid with a mixture of copper, silver and lead that produces a black enamel-like material called niello. They weigh almost exactly eight Roman ounces which suggests a deliberate cutting so they could be used as bullion for their metal weight.

Two of the fragments are all that remains of a large silver dish decorated with a beaded rim and a geometric border with floral accents and portrait busts. The border is gilded and inlaid with a mixture of copper, silver and lead that produces a black enamel-like material called niello. They weigh almost exactly eight Roman ounces which suggests a deliberate cutting so they could be used as bullion for their metal weight.

From the curve of the edges it’s clear that the pieces are quite small relative to the overall size of the platter but we didn’t know just how small they were until laser scanning allowed experts at the National Museums of Scotland to create a digital reconstruction. The complete dish was an impressive 70 centimeters (27.56 inches) in diameter making it one of the largest dishes known from the Roman world. It would have been used to carry food on the most important occasions.

From the curve of the edges it’s clear that the pieces are quite small relative to the overall size of the platter but we didn’t know just how small they were until laser scanning allowed experts at the National Museums of Scotland to create a digital reconstruction. The complete dish was an impressive 70 centimeters (27.56 inches) in diameter making it one of the largest dishes known from the Roman world. It would have been used to carry food on the most important occasions.

That floral decoration in the middle of the platter is speculative since the surviving fragments are both edge pieces. A similar dish found in Switzerland had an engraved medallion in the middle which served as the model.

Here’s video of the digital reconstruction: