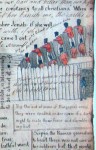

The full body scanners that have contributed so much to the hell that is modern air travel have just redeemed themselves in my eyes. Dr. J. Bianca Jackson of the University of Rochester used terahertz spectroscopy, the same electromagnetic radiation lying between kitchen microwaves and the infrared in your remote control that looks through your clothes at airports, to examine a fresco from the Louvre’s Campana collection. Underneath Trois hommes armés de lances (Three men armed with lances), a surface fresco in Roman style that was applied to an ancient wall in the 19th century, she found a face, part of what is probably an original Roman-era fresco.

The full body scanners that have contributed so much to the hell that is modern air travel have just redeemed themselves in my eyes. Dr. J. Bianca Jackson of the University of Rochester used terahertz spectroscopy, the same electromagnetic radiation lying between kitchen microwaves and the infrared in your remote control that looks through your clothes at airports, to examine a fresco from the Louvre’s Campana collection. Underneath Trois hommes armés de lances (Three men armed with lances), a surface fresco in Roman style that was applied to an ancient wall in the 19th century, she found a face, part of what is probably an original Roman-era fresco.

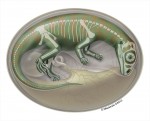

This an important breakthrough because the body scanning technology found something that none of the other imagining technologies — X-ray, ultraviolet, infrared, microscopy — in use today were able to detect. An analysis using X-ray fluorescence first confirmed that there might be something under the surface, but there were no specifics. It could have been anything — a textural change, a different material beneath the plaster — or nothing at all.

“No previous imaging technique, including almost half a dozen commonly used to detect hidden images below paintings, forged signatures of artists and other information not visible on the surface has revealed a lost image in this fresco,” Jackson said. “This opens to door to wider use of the technology in the world of art, and we also used the method to study a Russian religious icon and the walls of a mud hut in one of humanity’s first settlements in what was ancient Turkey.”

Terahertz spectroscopy is well-suited to conservation use because it’s a such a mild form of radiation it doesn’t harm the object being studied even in the smallest way. With so many systems used for conservation purposes, there’s a price to pay in deterioration of the artifact being conserved. Even X-rays and ultraviolet, non-invasive though they are, still cause some damage on a molecular level.

Terahertz spectroscopy is well-suited to conservation use because it’s a such a mild form of radiation it doesn’t harm the object being studied even in the smallest way. With so many systems used for conservation purposes, there’s a price to pay in deterioration of the artifact being conserved. Even X-rays and ultraviolet, non-invasive though they are, still cause some damage on a molecular level.

There’s no way at present to determine the date of the newly discovered face, but the art history strongly suggests it’s an original Roman fresco. Trois hommes armés de lances is one of three fragmentary ancient frescoed walls at the Louvre that were acquired by Giampietro Campana, a 19th century collector who was director of the Vatican pawnbroking charity Monte di Pietà and an amateur but very much accomplished archaeologist. His access to Papal properties gave him the opportunity to excavate in the heart of ancient Rome and Etruria. He made several major discoveries like the columbarium of Pomponius Hylas which he published in scholarly journals.

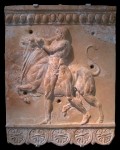

He also paid attention to artifacts that nobody before him had considered worthwhile. The terracotta reliefs used as decorative architectural elements along the roof edges and walls of public buildings still bear his name — Campana reliefs — because in the mid-19th century when archaeology was in its infancy, diggers were looking for big treasures, important works of art, jewelry, fancy things, not roof tiles. Campana alone recognized their historical and aesthetic significance.

He loved the splashy stuff too, mind you. From his excavations and from extensive purchases he built a private collection of sculpture, pottery, gold, jewels, that was one of the greatest ever assembled. His palazzo at the corner of Via del Babuino and Piazza del Popolo, which if you know Rome at all is a location TO DIE FOR, also served as his personal museum, although only people with letters of introduction were allowed to visit and only one day a week. One of those visitors, who probably needed no letters of introduction, was Pope Pius IX who went to see Campana’s collection in 1846.

He loved the splashy stuff too, mind you. From his excavations and from extensive purchases he built a private collection of sculpture, pottery, gold, jewels, that was one of the greatest ever assembled. His palazzo at the corner of Via del Babuino and Piazza del Popolo, which if you know Rome at all is a location TO DIE FOR, also served as his personal museum, although only people with letters of introduction were allowed to visit and only one day a week. One of those visitors, who probably needed no letters of introduction, was Pope Pius IX who went to see Campana’s collection in 1846.

Notwithstanding his expertise and genuine scholarly bent when it came to archaeology, Campana, or rather his restorers, had a very heavy hand by our standards. Hell, even by 19th century standards they systematically blurred line between restoration and fraud. The three men armed with spears are actually composites. They were created by (rather sloppily, actually) sticking together random fresco fragments. The fragments were all genuinely ancient, but it was a restorer who created the composition, assembled and stuck the pieces together to make them look like a full sized fresco. The restorer does not appear to have attempted to integrated the old picture into the new, as the placement of the newly found fresco proves.

There is very little documentation of the Campana collection. We don’t know who restored what or what the intent was. It’s unlikely to have been larceny by false promise, if I may invoke my Law & Order-derived legalese. Campana wasn’t much of a seller. He liked to buy and keep. What’s more likely is that the original painting was covered up with this chunky plaster mosaic just to make it look better, more important, more handsome, more worthy of its rarified surroundings in the Campana museum.

There is very little documentation of the Campana collection. We don’t know who restored what or what the intent was. It’s unlikely to have been larceny by false promise, if I may invoke my Law & Order-derived legalese. Campana wasn’t much of a seller. He liked to buy and keep. What’s more likely is that the original painting was covered up with this chunky plaster mosaic just to make it look better, more important, more handsome, more worthy of its rarified surroundings in the Campana museum.

Giampietro Campana never did get his museum made. In November of 1857, he was arrested for embezzlement of which he was guilty beyond any sliver of a shadow of doubt. In July of the next year, he was convicted and sentenced to 20 years in the galleys and to pay a massive fine. His sentence was commuted to exile. On 28 April 1859, Giampietro Campana gave his collection, much of which he had used as collateral on loans, to the Papacy, keeping only the furniture.

To reimburse Campana’s creditors (starting with itself) the Church did something so short-sighted, so wrong, so stupid I can barely stand to write it: they auctioned off his entire collection. England bought some of it for its new Kensington museum. Russia bought almost 500 antique vases, statues and jewelry for the Hermitage. The lion’s share went to Napoleon III who got first dibs on anything in the catalog before the sale started. He bought everything that was remaining: 11,835 artifacts for 4.8 million francs. Most of that massive collection went to the Louvre where today it has a room of its own, the Campana gallery. The only thing from the Campana collection that the Pope kept was 400 Roman and Byzantine gold coins.

Campana returned to Rome after the Unification of Italy in 1870. He died ten years later, his epic collection scattered to great museums around the world. After his death, his palazzo on the Piazza del Popolo was razed and built over.