One hundred years and one month to the day after the birth of John Snow, the first anesthesiologist in the UK, the man who identified that cholera was transmitted by the ingestion of water contaminated by feces and who performed the first modern epidemiological study to defeat that dread disease, the British medical journal The Lancet has finally published a correction to the paltry obituary they ran when he died far too soon at the age of 45 in 1858.

One hundred years and one month to the day after the birth of John Snow, the first anesthesiologist in the UK, the man who identified that cholera was transmitted by the ingestion of water contaminated by feces and who performed the first modern epidemiological study to defeat that dread disease, the British medical journal The Lancet has finally published a correction to the paltry obituary they ran when he died far too soon at the age of 45 in 1858.

The Lancet wishes to correct, after an unduly prolonged period of reflection, an impression that it may have given in its obituary of Dr John Snow on June 26, 1858. The obituary briefly stated:

“Dr John Snow: This well-known physician died at noon, on the 16th instant, at his house in Sackville Street, from an attack of apoplexy. His researches on chloroform and other anaesthetics were appreciated by the profession.”

The journal accepts that some readers may wrongly have inferred that The Lancet failed to recognise Dr Snow’s remarkable achievements in the field of epidemiology and, in particular, his visionary work in deducing the mode of transmission of epidemic cholera. The Editor would also like to add that comments such as “In riding his hobby very hard, he has fallen down through a gully-hole and has never since been able to get out again” and “Has he any facts to show in proof? No!”, published in an Editorial on Dr Snow’s theories in 1855, were perhaps somewhat overly negative in tone.

:giggle: The modern Lancet appears to have a gift for understatement commensurate with the Victorian-era publication’s gift for hyperbolic metaphor.

The cause of this shameful oversight was Thomas Wakley, founder and editor of The Lancet and avid social reformer whose efforts to shut down noxious polluting factories John Snow had damaged by testifying before a Select Committee of Parliament that miasmic fumes from tanneries and soap factories were not the cause of cholera epidemics. That was the proximate cause of the 1855 editorial excoriating Snow’s gully-hole and it doubtless played a major role in the journal’s editorial decision to publish a weak, two-sentence death notice for a great medical innovator three years later.

The cause of this shameful oversight was Thomas Wakley, founder and editor of The Lancet and avid social reformer whose efforts to shut down noxious polluting factories John Snow had damaged by testifying before a Select Committee of Parliament that miasmic fumes from tanneries and soap factories were not the cause of cholera epidemics. That was the proximate cause of the 1855 editorial excoriating Snow’s gully-hole and it doubtless played a major role in the journal’s editorial decision to publish a weak, two-sentence death notice for a great medical innovator three years later.

Wakley and The Lancet had gone up against Snow on various medical issues from the beginning of Snow’s career when he made his bones as a newly minted member of the Royal College of Surgeons of England by writing letters to the editor rebutting published articles. His letters about the dangers of the use of arsenic as a preservative in cadavers and on the physics of respiration were his first published works. Wakley wasn’t a fan. He was an old school physician who believed in the superiority of the inductive method — accumulation of facts leading to a general conclusion — and found Snow’s rebuttals excessively reliant on his own clinical experience. In the issue of May 25th, 1839, he refused to publish one of Snow’s letters posting instead a rather brutal iceburn:

“The remarks of Mr. John Snow on a recent communication from M. H., on the physiology of respiration, have been received. We cannot help thinking that Mr. Snow might better employ himself in producing something, than to criticizing the productions of others.”

Burned or not, John Snow actually took Thomas Wakley’s advice. He stopped sending letters to the editor and focused on a specialty that would ultimately tie together all the areas that he became known for: respiration, mechanisms and pathologies thereof. That interest was reflected in his first paper, On Distortions of the Chest and Spine in Children, from Enlargement of the Abdomen, published in the London Medical Gazette in April, 1841, which analyses the effect of abdominal deformity on breathing.

Five years later, his interest in respiration led him to investigate the brand new field of anesthesia, which at its heart was a question of how to walk the fine line between pain prevention and the suppression of respiration. When ether first came to England from the United States in 1846, it had a bad reputation. Snow created a delivery system that was more reliable — described in detail in 1847’s On the Inhalation of the Vapour of Ether in Surgical Operations — and became England’s first specialized anesthesiologist.

Five years later, his interest in respiration led him to investigate the brand new field of anesthesia, which at its heart was a question of how to walk the fine line between pain prevention and the suppression of respiration. When ether first came to England from the United States in 1846, it had a bad reputation. Snow created a delivery system that was more reliable — described in detail in 1847’s On the Inhalation of the Vapour of Ether in Surgical Operations — and became England’s first specialized anesthesiologist.

On April 7th, 1853, Snow was called to Buckingham Palace by Sir James Clark, Queen Victoria’s physician of 19 years, to administer chloroform to the Queen during the delivery of her eighth child, Prince Leopold. Her gave her small doses through a dainty handkerchief every time she had a contraction, enough to provide pain relief but not to render the royal body unconscious. According to Snow’s case book, the Queen was “very cheerful” after the successful delivery and “express[ed] herself much gratified with the effect of the chloroform.”

The Queen’s imprimatur granted chloroform and Dr. Snow a whole new legitimacy in medical circles and in the wider society. The Lancet not only disapproved, but actually refused to believe it had even happened. In an unsigned editorial probably written by Wakely, the Lancet disparaged the “rumor” that the Queen had been given chloroform because it had “unquestionably caused instantaneous death in a considerable number of cases” of surgical anesthesia, and therefore it stood to reason that “the obstetric physicians to whose ability the safety of our illustrious Queen is confided do not sanction the use of chloroform in natural labour.” The editorial made no distinction between analgesic use and anesthetic use.

It wasn’t all bad between Snow and The Lancet. In 1846 he wrote a letter to the editor expressing dismay at The Lancet‘s use of the term “allopathy” in an article about homeopathy because it lent legitimacy to the practice. The letter was published and the editor agreed. Snow published 15 papers in The Lancet during his career, eight of them after the 1853 editorial, several of them about chloroform.

In 1849, Snow published his first paper on the cause of cholera. As an expert in respiration, he found the conventional wisdom that the disease was contracted by inhaling the miasmic vapours of decomposition unsatisfying. If the disease is conveyed by inhalation into the blood stream, then why are its symptoms centered in the alimentary system? Ten years before Pasteur and without realizing microscopic bacilli were to blame, Snow recognized that whatever caused cholera was some small, highly reproductive creature swallowed by its victims.

Having rejected effluvia and the poisoning of the blood in the first instance, and being led to the conclusion that the disease is communicated by something that acts directly on the alimentary canal, the excretions of the sick at once suggest themselves as containing some material which, being accidentally swallowed, might attach itself to the mucous membrane of the small intestines, and there multiply itself by the appropriation of surrounding matter, in virtue of molecular changes going on within it, or capable of going on, as soon as it is placed in congenial circumstances

He continued to research the disease for years after the initial publication. He hit the streets, mapping out the affected areas, noting sources of water, sewage, contaminants, population density, overall health of the residents, all the stuff that epidemiologists do today only he did it first. In 1854, a major outbreak of cholera devastated Soho. By interviewing the locals, Snow pinpointed the source as one specific water pump on Broad Street. He convinced authorities to remove the pump handle making it impossible to use. The outbreak ended.

He continued to research the disease for years after the initial publication. He hit the streets, mapping out the affected areas, noting sources of water, sewage, contaminants, population density, overall health of the residents, all the stuff that epidemiologists do today only he did it first. In 1854, a major outbreak of cholera devastated Soho. By interviewing the locals, Snow pinpointed the source as one specific water pump on Broad Street. He convinced authorities to remove the pump handle making it impossible to use. The outbreak ended.

The story of the Broad Street pump handle has become part of the Snow mythos, although he himself noted that the outbreak was already waning when the pump was disabled simply from people fleeing the area. Also, the council just returned the handle after the outbreak was over without doing anything about the cesspits that were contaminating the water being pumped. They were just covering all their bases. They didn’t particularly believe Snow’s theory and they preferred denial anyway because nobody likes to think they’re drinking their neighbors’ shit.

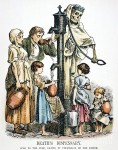

Snow’s research was pretty much dismissed by medical societies and journals too. Miasma theory held strong sway. Finally King Cholera pitted Snow and Wakley against each other in an arena where Wakley had been an intensely passionate advocate since he founded The Lancet in 1823: public health reform. Wakley was a dedicated activist, going up against the medical and political establishment in favor of the downtrodden again and again.

The 1855 Nuisances Removal and Diseases Prevention Act would have greatly reduced the fumes released by the many factories stinking up poor sections of London and other cities in England. Some of them would have had to close altogether. Wakley and many other medical professionals believed the putrid stenches belched by these establishments were sources of illness and epidemic diseases like cholera. The inhalation of effluvia from decomposing matter or diseased flesh, it was widely held, caused disease.

John Snow disagreed. His epidemiological research had shown that the highest concentration of cholera infection happened around water sources, not around glue factories no matter how many dead horses they had lying around. Here’s his testimony before the committee.

John Snow disagreed. His epidemiological research had shown that the highest concentration of cholera infection happened around water sources, not around glue factories no matter how many dead horses they had lying around. Here’s his testimony before the committee.

Q: “To what points would you desire to draw the attention of the Committee as regards the sanitary question?”

A: “I have paid a great deal of attention to epidemic diseases, more particularly to cholera, and in fact to the public health in general; and I have arrived at the conclusion with regard to what are called offensive trades, that many of them really do not assist in the propagation of epidemic diseases, and that in fact they are not injurious to the public health. I consider that if they were injurious to the public health they would be extremely so to the workmen engaged in those trades, and as far as I have been able to learn, that is not the case; and from the law of the diffusion of gases, it follows, that if they are not injurious to those actually upon the spot, where the trades are carried on, it is impossible they should be to persons further removed from the spot.”

Wakley responded with an eruption of editorial fury. The brief quote cited in The Lancet yesterday doesn’t begin to do it justice.

They have “scientific” evidence! They bring before the Committee a doctor and a barrister. They have formed an Association. They have a Secretary, a bone merchant, who has read the writings of Dr. Snow. Now, the theory of Dr. Snow tallies wonderfully with the views of the “Offensive Trades’ Association” — we beg pardon if that is not the right appellation — and so the Secretary puts himself in communication with Dr. Snow. And they could not possibly get a witness more to their purpose. Dr. Snow tells the Committee that the effluvia from bone-boiling are not in any way prejudicial to the health of the inhabitants of the district; that “ordinary decomposing matter will not produce disease in the ‘human subject.'” He is asked by Mr. Adderley (of the Committee), “Have you never known the blood poisoned by inhaling putrid matter?” (Snow’s response) “No; but by dissection-wounds the blood may be poisoned.” (Adderley asked) “Never by inhaling putrid gases?” (Snow responded) “No; gases produced by decomposition, when very concentrated, will produce sudden death; but when the person is not killed, if he recovers, he has no fever or illness.”

Dr. Snow next admits that gases from the decay of animal matter may produce vomiting but says this would not be injurious unless frequently repeated.

Is this scientific evidence? Is it consistent with itself? It is in accordance with the experience of men who have studied the question without being blinded by theories? […]

It will be very difficult to persuade us that the long-continued action of gases known to have such lethal powers, if concentrated, is not injurious to health, when in a state of dilution … and we presume that there is hardly a practitioner of experience and average powers of observation who does not daily observe the same thing. Why is it then, that Dr. Snow is singular in his opinion? Has he any fact to show in proof? No! But he has a theory, to the effect that animal matters are only injurious when swallowed! The lungs are proof against animal poisons; but the alimentary canal affords a ready inlet… The fact is that the well whence Dr. Snow draws all sanitary truth is the main sewer. His specus, or den, is a drain. In riding his hobby very hard, he has fallen down through a gully-hole and has never since been able to get out again. […]

In that dismal Acherontic stream is contained the one and only true cholera germ, and if you take care not to swallow that you are safe from harm. Smell it if you may, breathe it fearlessly, but don’t eat it.

The bill eventually passed, but the provisions against the “offensive trades” were significantly weakened. Although in 1856 The Lancet did publish two of Snow’s papers on how cholera is spread (The Mode of Propagation of Cholera and On the Supposed Influence of Offensive Trades on Mortality), Wakley’s rage against Snow still hadn’t dissipated sufficiently three years later to grant the man a proper obituary, something The Lancet did often for professionals of far less consequence who nobody remembers anymore.