One of Leonardo da Vinci’s many brilliant ideas was to create a musical instrument that combined the fingerwork of a keyboard with the sustained sound of a stringed instrument. He called it a viola organista and explored various mechanisms of foot-treadle operated rotating wheels that pull a bow across strings, sketching different designs for it in his notebooks including the Codex Atlanticus, (page 93r), now in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, and Manuscript H (page 28r) in Paris’ Bibliothèque de l’Institut de France. As far as we know none of these designs ever made it to the prototype stage.

One of Leonardo da Vinci’s many brilliant ideas was to create a musical instrument that combined the fingerwork of a keyboard with the sustained sound of a stringed instrument. He called it a viola organista and explored various mechanisms of foot-treadle operated rotating wheels that pull a bow across strings, sketching different designs for it in his notebooks including the Codex Atlanticus, (page 93r), now in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, and Manuscript H (page 28r) in Paris’ Bibliothèque de l’Institut de France. As far as we know none of these designs ever made it to the prototype stage.

Almost a hundred years later in 1575, church organist Hans Hyden of Nuremberg created the first functional bowed keyboard instrument operated by a foot-treadle. He used gut strings (later switched to metal when the gut strings failed to stay in tune) and five or six parchment-wrapped wheels which, when turned by the treadle and a hand-crank at the far end operated by a helper, would be drawn against individual strings determined by which keys were played. Hyden claimed his instrument could produce crescendos, diminuendos, vibrato and sustain notes indefinitely solely through finger pressure on the keys. He even said it could duplicate the voice of a drunk man.

He called it a Geigenwerk (meaning “fiddle organ”) which is the German translation of da Vinci’s name for it, but although some sources imply or claim he based his design on da Vinci’s, I have serious doubts about that. Leonardo was hugely famous in his lifetime and after, but it was for his art, not his notebooks. Bequeathed to his friend and apprentice Francesco Melzi, the notebooks were sold off piecemeal by the Melzi family after Francesco’s death in 1579. Pages were scattered to courts and collectors all over Europe. Some of Leonardo’s notes on painting were published in 1651, but the bulk of the notebooks only made it into print in the 19th century. I don’t see how Hyden could have had access to them.

He called it a Geigenwerk (meaning “fiddle organ”) which is the German translation of da Vinci’s name for it, but although some sources imply or claim he based his design on da Vinci’s, I have serious doubts about that. Leonardo was hugely famous in his lifetime and after, but it was for his art, not his notebooks. Bequeathed to his friend and apprentice Francesco Melzi, the notebooks were sold off piecemeal by the Melzi family after Francesco’s death in 1579. Pages were scattered to courts and collectors all over Europe. Some of Leonardo’s notes on painting were published in 1651, but the bulk of the notebooks only made it into print in the 19th century. I don’t see how Hyden could have had access to them.

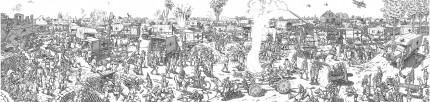

None of Hyden’s Geigenwerks — he’s reputed to have built as many as 32 of them although only two are thoroughly documented — have survived. The details of its operation and the sole surviving illustration of the instrument have come down to us from German composer and music theorist Michael Praetorius who included one of Hyden’s original pamphlets describing the machine and a woodcut of it in the appendix to the second volume of his Syntagma Musicum, published as the Theatrum Instrumentorum seu Sciagraphia in 1620.

Imitations have survived, the earliest of which made by Spanish monk Raymundo Truchado in 1625. It is now in Brussels’ Musical Instruments Museum. Truchado’s Geigenwerk is an oddly truncated little thing which could only have been played sitting on the ground or perched on a low table. It had no foot-treadle, just the hand-crank in the back. The instrument is no longer playable today. Given its design it doesn’t look like it was ever comfortably playable at all, but it must have been worth it because it was used on occasion in the Cathedral of Toledo until the late 18th century.

Imitations have survived, the earliest of which made by Spanish monk Raymundo Truchado in 1625. It is now in Brussels’ Musical Instruments Museum. Truchado’s Geigenwerk is an oddly truncated little thing which could only have been played sitting on the ground or perched on a low table. It had no foot-treadle, just the hand-crank in the back. The instrument is no longer playable today. Given its design it doesn’t look like it was ever comfortably playable at all, but it must have been worth it because it was used on occasion in the Cathedral of Toledo until the late 18th century.

Since then, many people have made versions of the bowed keyboard instrument, some of them using Leonardo’s designs as the starting point. They haven’t all been successful. This 2009 version of a portable viola organista made from one of Leonardo’s sketches is serving hilariously awkward one-man-band realness. Pianist and keyboard instrument builder Akio Obuchi has made several Geigenwerks which can indeed produce the kind of sounds Hyden described.

Now Polish concert pianist Slawomir Zubrzycki has joined the fray with a viola organista that is as beautiful to look at as it is to listen to.

Now Polish concert pianist Slawomir Zubrzycki has joined the fray with a viola organista that is as beautiful to look at as it is to listen to.

The instrument’s exterior is painted in a rich hue of midnight blue adorned with golden swirls painted on the side. The inside of its lid is a deep raspberry inscribed with a Latin quote in gold leaf by 12th-century German nun, mystic and philosopher, Saint Hildegard.

“Holy prophets and scholars immersed in the sea of arts both human and divine, dreamt up a multitude of instruments to delight the soul,” it says.

The flat bed of its interior is lined with golden spruce. Sixty-one gleaming steel strings run across it, similar to the inside of a baby grand. Each one is connected to the keyboard complete with smaller black keys for sharp and flat notes. But unlike a piano, it has no hammered dulcimers. Instead, there are four spinning wheels wrapped in horse tail hair, like violin bows. To turn them, Zubrzycki pumps a peddle below the keyboard connected to a crankshaft.

As he tinkles the keys, they press the strings down onto the wheels emitting rich, sonorous tones reminiscent of a cello, an organ and even an accordion.

It took him three years and $9,700 to build the instrument. Zubrzycki’s viola organista had its debut last month at the International Royal Krakow Piano Festival where it was given a standing ovation by an audience of virtuoso musicians and music lovers. It truly is magnificent, so rich and full you keep looking for the rest of the orchestra.

If you only have the time to watch one video, start with this one in which Zubrzycki tells the story of how he made the piece and plays it in his home. There are great closeups of the instrument and its moving parts. Click the CC icon for English subtitles.

[youtube=http://youtu.be/gOrn_z9m9lU&w=430]

Here he is performing a piece by Carl Friederich Abel for the viola da gamba (the predecessor of the cello) at Krakow’s Church of St. Peter and Paul on October 21st:

[youtube=http://youtu.be/JG7qvkGZkug&w=430]

This are snippets of several pieces he played at the International Royal Krakow Piano Festival:

[youtube=http://youtu.be/sv3py3Ap8_Y&w=430]