A cast iron Mr. Peanut who once stood debonair watch on the fence post of a Planters factory will now stand debonair watch at the National Museum of American History. It was donated by Kraft Foods, which acquired the Planters brand when it bought Nabisco in 2000, and will be part of the museum’s upcoming American Enterprise exhibition which opens in 2015. Mr. Peanut will adorn the exhibition’s Marketing Moments section, as suits so iconic a brand logo.

A cast iron Mr. Peanut who once stood debonair watch on the fence post of a Planters factory will now stand debonair watch at the National Museum of American History. It was donated by Kraft Foods, which acquired the Planters brand when it bought Nabisco in 2000, and will be part of the museum’s upcoming American Enterprise exhibition which opens in 2015. Mr. Peanut will adorn the exhibition’s Marketing Moments section, as suits so iconic a brand logo.

“American advertising has gone through a tremendous transformation since the early years of the nation,” said John Gray, director of the museum. “But while it has become a high-tech industry deeply affecting the American experience, icons like Mr. Peanut demonstrate the resilience of branding and the use of spokes-characters throughout much of that transformation.”

It’s fitting that an exhibition on the history of American business should prominently feature the work of two first-generation Italian immigrants and one second-generation. The Planters Peanut Company was founded in 1906 by 29-year-old Amedeo Obici, an immigrant who had left his hometown of Oderzo, 40 miles northeast of Venice, when he was just 11 years old to join his uncle in Scranton, Pennsylvania. He worked at a cigar factory making 80 cents a week while he learned English going to night school. A year later he moved to Wilkes-Barre where he worked at a fruit stand that also sold roasted peanuts.

It’s fitting that an exhibition on the history of American business should prominently feature the work of two first-generation Italian immigrants and one second-generation. The Planters Peanut Company was founded in 1906 by 29-year-old Amedeo Obici, an immigrant who had left his hometown of Oderzo, 40 miles northeast of Venice, when he was just 11 years old to join his uncle in Scranton, Pennsylvania. He worked at a cigar factory making 80 cents a week while he learned English going to night school. A year later he moved to Wilkes-Barre where he worked at a fruit stand that also sold roasted peanuts.

This inspired the young Amedeo to get a fruit stand of his own with a peanut cart and a cheap roaster that he modified himself from scrapyard parts. He added a steam whistle so his cart would go off like a tea kettle when the roasting was done and an automated stirring mechanism which allowed him to focus on his customers without concern that the peanuts would burn. Showing an early understanding of marketing that would soon blossom into the dandiest of anthropomorphic peanuts, Obici called himself “The Peanut Specialist” and was soon doing very brisk business from the back of a horse-drawn wagon. By the time he was 18 years old in 1895, Amedeo had saved enough money to bring his mother and siblings to live with him in the United States and still had money left over to buy his own restaurant that specialized in roasted nuts and, weirdly, oyster stew.

There he experimented further with the roasting process. He added salt — can you imagine the days before peanuts were a salty snack? — and, since salt sticks better to peeled and skinned peanuts, started blanching them first to remove their outerwear before roasting them in oil and salting them. He also made chocolate-covered peanuts to cover all bases, savory and sweet.

There he experimented further with the roasting process. He added salt — can you imagine the days before peanuts were a salty snack? — and, since salt sticks better to peeled and skinned peanuts, started blanching them first to remove their outerwear before roasting them in oil and salting them. He also made chocolate-covered peanuts to cover all bases, savory and sweet.

It was when he joined forces with his future brother-in-law Mario Peruzzi that the Planters we know today was born. Peruzzi invented a superior process for blanching and roasting whole peanuts. When the Planters Peanut Company opened its doors in 1906, their focus was on quality. Obici wanted to elevate the lowly peanut, then considered animal feed, or at best for people who couldn’t afford anything better (hence the phrase “peanut gallery,” meaning the distant seats cheap enough for peanut-eaters). That’s why he picked the name “Planters,” because the thought it redolent of the landed aristocracy.

The company was successful, its product genuinely superior to many of its competitors’. To cut out the middlemen and decrease exorbitant transportation costs, in 1913 Obici moved the main peanut processing factory to Suffolk, Virginia, where the peanut plantations were. That’s where the second-generation Italian comes into the picture. In 1916, annoyed by the many inferior imitations of Planters’ roasted nuts that had sprung up in the wake of their success, the company ran a contest for a new trademark design that would appeal to adults and children alike. The chosen design would win five dollars. The lucky winner was a 13-year-old Suffolk boy by the name of Anthony Gentile. He drew a smiling peanut in the shell with arms, legs and in at least one drawing, a cane. He named it “Mr. P. Nut Planter — from Virginia.”

The company was successful, its product genuinely superior to many of its competitors’. To cut out the middlemen and decrease exorbitant transportation costs, in 1913 Obici moved the main peanut processing factory to Suffolk, Virginia, where the peanut plantations were. That’s where the second-generation Italian comes into the picture. In 1916, annoyed by the many inferior imitations of Planters’ roasted nuts that had sprung up in the wake of their success, the company ran a contest for a new trademark design that would appeal to adults and children alike. The chosen design would win five dollars. The lucky winner was a 13-year-old Suffolk boy by the name of Anthony Gentile. He drew a smiling peanut in the shell with arms, legs and in at least one drawing, a cane. He named it “Mr. P. Nut Planter — from Virginia.”

There is some question as to whether there may have been some bias in the selection. The Italian community in Suffolk was small and it’s highly unlikely that the Obicis and Gentiles were strangers. They certainly weren’t from that point forward. Amedeo Obici payed Anthony’s way through college and medical school, and he paid for the college education of all of Anthony’s surviving siblings (minus one who didn’t want to go). Anthony Gentile died of a heart attack when he was just 36 years old.

He lives on his immortal creation, however. Obici sent Anthony’s drawings to a commercial artist in Wilkes-Barre to gussy them up for the campaign. The artist, whose name has sadly not come down to us, added the top hat, white gloves, monocle and spats to give Mr. Peanut that classy look Mr. Obici was always keen to project on his modest fare. The first official Mr. Peanut made his debut in the April 20th, 1918, issue of the Saturday Evening Post. Notice the focus in the early ads on branding, on the

He lives on his immortal creation, however. Obici sent Anthony’s drawings to a commercial artist in Wilkes-Barre to gussy them up for the campaign. The artist, whose name has sadly not come down to us, added the top hat, white gloves, monocle and spats to give Mr. Peanut that classy look Mr. Obici was always keen to project on his modest fare. The first official Mr. Peanut made his debut in the April 20th, 1918, issue of the Saturday Evening Post. Notice the focus in the early ads on branding, on the  unmistakable identification of the quality genuine Planters peanut versus the pale imitators who have neither the transparent bag nor the Fred Astaire of peanuts to distinguish them. This was the first national advertising campaign for roast salted nuts.

unmistakable identification of the quality genuine Planters peanut versus the pale imitators who have neither the transparent bag nor the Fred Astaire of peanuts to distinguish them. This was the first national advertising campaign for roast salted nuts.

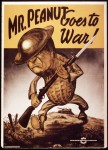

He was a raging success, soon becoming a highly coveted item in his own right thanks to the company’s vast array of promotional products. Cast iron versions like the one now in the Smithsonian decorated Planters factories and along with other such pieces pioneered the practice of outdoor three-dimensional advertising. He was even enlisted in the war effort, appearing butched up and stripped of all his fancy accessories on one of the greatest of all World War II propaganda posters issued by the Department of Agriculture to promote the many uses of peanuts in wartime.

To this day Mr. Peanut remains highly collectible and widely beloved. Planters ran an online poll in 2006 asking which new accessory — bow tie, cufflinks or pocketwatch — Mr. Peanut should don and all were rejected in favor of keeping him just as he is.

To this day Mr. Peanut remains highly collectible and widely beloved. Planters ran an online poll in 2006 asking which new accessory — bow tie, cufflinks or pocketwatch — Mr. Peanut should don and all were rejected in favor of keeping him just as he is.

For more about the National Museum of American History’s American Enterprise exhibition, see its dedicated website. It has an overview of the show and some interesting articles like this one about the history of pawnshops and their symbol.