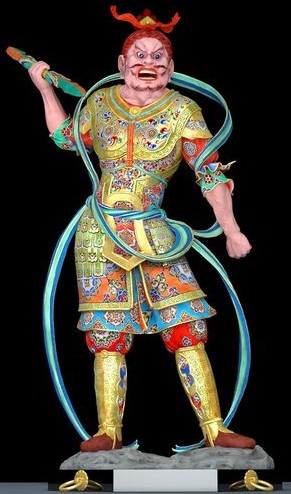

When the life-sized clay statue of the Buddhist deity Shukongojin was made for the Todaiji Temple in Nara, southeastern Japan, in 733 A.D., it was painted in vibrant colors and liberally gilded. Although much of the polychromy has been lost over time, there’s still an unusual amount of color paint and gilding surviving on the surface. So much has pigment has survived because Shukongojin is a hidden god — he is extra powerful because he is kept behind closed doors at all times and only revealed to the public one day a year — and has therefore been protected from exposure to the elements and our various emanations and effluvia.

The particularly great state of preservation of this oldest Shukongojin figure in the country has made it possible to extrapolate what the whole statue looked like when it was new 1,280 years ago. Researchers from the Tokyo University of the Arts and the Tokyo University of Science spent two years studying the statue to detect trace pigment remnants and recreating the original colors digitally.

The result is as striking in 8th century clay as it is in first century marble:

Gold was an indicator of divinity in Japanese Buddhist iconography, while red symbolized the quelling of demons and protection from illness. Shukongojin is a protector deity, the thunderbolt-bearing guardian of the laws of Buddhism and its faithful. His furious expression, crowned in bright red hair, and his thunderbolt ready to strike ward off the evil spirits who would bedevil the devoted at prayer in the temple. He was originally an Indian deity, one of the vajrapani or thunderbolt-holders who were said to have been personal guardians of the historical Buddha. His thunderbolt broke everything it was flung at while being itself unbreakable, a symbol of faith’s ability to destroy evil without being damaged by the encounter.

The bright colors and elaborate adornment served a political function as well. Emperor Shomu (reigned 724-749 A.D.) saw the establishment of government-controlled Buddhist temples and shrines as a means to unify and protect the country. His reign had been plagued with rebellions, smallpox outbreaks and crop failures. In 743, he issued an edict requiring people to help build temples and shrines in every province, with Todaiji as the head of all provincial temples. He believed a new, widespread piety would appeal to the Buddha and spare the country further disasters. Shukongojin, with his full armour, gold shine, blinding colors and powerful intensity of expression, was modeled after depictions of Chinese guardian generals. His role is religious, but his intimidating presence and elaborately decorated outfit are meant to convey the protection of a unified faith, already well-established in India and China, a protection inextricably linked to the emperor’s government at this time.

This particular Shukongojin has another connection to the early history of Buddhism in Japan. According to the Nihon Ryoiki, the oldest collection of Buddhist myths and legends in Japan (it dates to the late 8th/early 9th centuries), the monk Roben, second patriarch of the Kegon school of Buddhism and founder of the Todaiji Temple, was helped in the creation of the temple by a magical sculpture of Shikkongoushin. Tradition has it that this is that very Shikkongoushin who supported Roben’s work. It was first made for the Kinshoji, the temple Roben established in 733 a decade before the emperor ordered construction of Todaiji. The former Kinshoji is now the Hokkedo (Lotus Hall), the oldest building in the Todaiji temple complex, and is still Shikkongoushin’s home today.