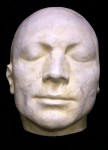

Philippe Charlier, forensic pathologist and indefatigable researcher of historical medical conundrums, and Philippe Froesch, facial reconstruction specialist with Visual Forensic in Barcelona, Spain, have created an intense facial reconstruction of French Revolutionary leader Maximilien de Robespierre. The main source for the image is a plaster copy of a death mask Madame Tussaud claimed* to have made from his decapitated head after he was guillotined on July 28th, 1794.

Philippe Charlier, forensic pathologist and indefatigable researcher of historical medical conundrums, and Philippe Froesch, facial reconstruction specialist with Visual Forensic in Barcelona, Spain, have created an intense facial reconstruction of French Revolutionary leader Maximilien de Robespierre. The main source for the image is a plaster copy of a death mask Madame Tussaud claimed* to have made from his decapitated head after he was guillotined on July 28th, 1794.

Froesch used a hand-held scanner to create a 3D computer model of the face. He then added details to the smooth-faced model, like the more than 100 pockmarks caused by a bad case of smallpox he suffered 30 years before his death when he was a boy of six. The eyes were a particular challenge because the closed eyelids didn’t leave an impression in the plaster so they were drawn on. Using an FBI technique that allowed him to calculate the eye size and position from marks left on the mask by the corneas, he was able to correct the crude eyelid line. (There are some pictures of the eye work on the Visual Forensic website.)

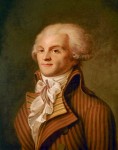

The end result is very far from the mild face conveyed in his portraits:

Portrait artists were then and are now notoriously heavy-handed with the painterly Photoshop, and the uncertainties of the French Revolution would have made it a very bad idea to cross someone who could easily have you decapitated, but damn yo, if this reconstruction is the real deal, I hope Robespierre paid those painters generously.

Charlier and Froesch also studied contemporary accounts of Robespierre and those coupled with the newly reconstructed face, suggested a possible diagnosis for the illness known to have afflicted him.

Several clinical signs were described by contemporary witnesses: vision problems, nose bleeds (“he covered his pillow of fresh blood each night”), jaundice (“yellow coloured skin and eyes”), asthenia (“continuous tiredness”), recurrent leg ulcers, and frequent facial skin disease associated with scars of a previous smallpox infection. He also had permanent eye and mouth twitching. The symptoms worsened between 1790 and 1794. […]

The retrospective diagnosis that includes all these symptoms is diffuse sarcoidosis with ophthalmic, upper-respiratory-tract (nose or sinus mucosa), and liver or pancreas involvement.

Sarcoidosis is a rare autoimmune syndrome where granulomas (collections of immune system cells) develop in any number of organs. Symptoms include all the ones mentioned above and a slew of others. The skin can be affected too, causing nodules or lesions that last several weeks. Treatment these days is corticosteroids, but Robespierre died 80 years before the disease was identified by Sir Jonathan Hutchinson and 160 years before the introduction of prednisone. His treatment would have been more along the lines of bleeding and dietary changes.

The reconstruction has not gone over well with Robespierre fans, for some reason.

When the first 3D images emerged earlier this month, far left politicians denounced it as a plot to make their hero look evil.

“These days, with 3D, heroes are derided and tyrant kings are magnified … A sad era,” wrote Alexis Corbiere, a Paris official and member of the Leftist Front, which is among many to view Robespierre as a champion of social justice.

*Some historians think Madame Toussaud lied about the authenticity of the mask to promote her work, that the Revolutionary authorities would have had no interest in preserving Robespierre’s visage and would want to bury him and the rest of the daily pile of bodies as soon as possible. However, the Terror leaders did commission her to make death masks of King Louis XVI, Queen Marie Antoinette and many other notable victims of Madame Guillotine. There’s no reason to assume they’d be inimical to the very idea of preserving the faces of whoever they deemed enemies of the Revolution. Masks of aristocrats and Terror victims were paraded through the streets.

*Some historians think Madame Toussaud lied about the authenticity of the mask to promote her work, that the Revolutionary authorities would have had no interest in preserving Robespierre’s visage and would want to bury him and the rest of the daily pile of bodies as soon as possible. However, the Terror leaders did commission her to make death masks of King Louis XVI, Queen Marie Antoinette and many other notable victims of Madame Guillotine. There’s no reason to assume they’d be inimical to the very idea of preserving the faces of whoever they deemed enemies of the Revolution. Masks of aristocrats and Terror victims were paraded through the streets.

The original of the mask is in Madame Tussauds London. The copies Froesch used are from the Granet Museum in Aix-en-Provence and the National Museum of Natural History in Paris. They were commissioned by artist and phrenologist Pierre Marie Alexandre Dumoutier who amassed a large collection of casts as part of his fascination with the bumps on people’s heads.