An 18th century book of musical scores with a dashingly Hornblower-like history has been identified as an extremely rare, probably unique, survival of early Chinese music. The book has been in St John’s College library at Cambridge University for 210 years. It was known to be there, but none of the resident scholars knew much about it beyond it being an “odd little book.” A colleague suggested visiting Chinese scholar Dr. Jian Yiang check out the slender volume and he immediately recognized it as a rare collection of musical scores written in Gongche notation. When he consulted with other experts, they confirmed that they had never seen this particular title before which means it may well be one of a kind.

An 18th century book of musical scores with a dashingly Hornblower-like history has been identified as an extremely rare, probably unique, survival of early Chinese music. The book has been in St John’s College library at Cambridge University for 210 years. It was known to be there, but none of the resident scholars knew much about it beyond it being an “odd little book.” A colleague suggested visiting Chinese scholar Dr. Jian Yiang check out the slender volume and he immediately recognized it as a rare collection of musical scores written in Gongche notation. When he consulted with other experts, they confirmed that they had never seen this particular title before which means it may well be one of a kind.

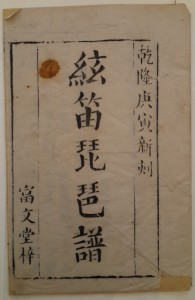

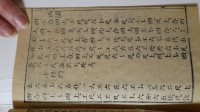

The book itself is entitled Xian Di Pipa Pu, which means the musical score for Chinese flute and “pipa” (a Chinese lute). It contains a condensed introduction to three instruments – “Xiao” (a type of recorder), “Di” (Chinese flute) and “Sanxian” (the three-stringed Chinese lute). This is followed by 13 pieces of music in the traditional Gongche notation.

It is particularly valuable because attempts to understand China’s musical heritage have been thwarted by a lack of reliable historical documents. Zhiwu Wu, Professor of Chinese Music at Xinghai Conservatory in Guangzhou, who has analysed Yang’s find, said: “The discovery of this rare volume of pre-modern Chinese musical notation might contribute a great deal to current research and performance of Chinese traditional music and some of the pieces included might be the earliest and only source available.”

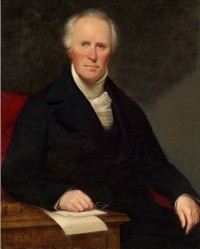

Xian Di Pipa Pu came very close to destruction before scholars got the chance to learn from it. The book was acquired by the Reverend James Inman, mathematician, astronomer and an alumnus of St John’s College, Cambridge, when he was in Whampoa in Canton (today Guangzhou), China, in December of 1803. The next month he was on his way back to England, sailing on the East India ship Warley, a 1,475-ton merchant ship that was part of the British China Fleet.

Xian Di Pipa Pu came very close to destruction before scholars got the chance to learn from it. The book was acquired by the Reverend James Inman, mathematician, astronomer and an alumnus of St John’s College, Cambridge, when he was in Whampoa in Canton (today Guangzhou), China, in December of 1803. The next month he was on his way back to England, sailing on the East India ship Warley, a 1,475-ton merchant ship that was part of the British China Fleet.

The East Indiamen, as these ships were known, were large and heavy and could carry up to 36 guns so they were strong enough to fend off privateers and from a distance could be confused for small ships of the line, but they were not military vessels. The fleet that set sail with Inman in January of 1804 carried passengers and an immensely valuable cargo: tea, silk and porcelain that today would be worth more than a billion dollars. They had no military escort, just a single East India Company brig, however, and the convey was a highly desirable target. With the uneasy peace between France and Britain about to be broken in May of 1803, Napoleon had dispatched a squadron of warships under the command of Contre-Admiral Charles-Alexandre Durand Linois to India with the explicit purpose of interrupting the East India trade, a load-bearing wall of the British economy. Intercepting so rich a fleet would be a major coup.

Linois’ spies had reported to him when the British China Fleet sailed and his ships had been patrolling the area for a month looking for it. On February 14th, 1804, the French and British came face to face in front of the island of Pulo Aura near the Straits of Malacca off the Malaysian coast. Because Linois had heard from his spies that the fleet would have military escorts (false information that may have been deliberately planted by the British), he was cautious and did not attack right away.

Linois’ spies had reported to him when the British China Fleet sailed and his ships had been patrolling the area for a month looking for it. On February 14th, 1804, the French and British came face to face in front of the island of Pulo Aura near the Straits of Malacca off the Malaysian coast. Because Linois had heard from his spies that the fleet would have military escorts (false information that may have been deliberately planted by the British), he was cautious and did not attack right away.

Commodore Nathaniel Dance, commander of the British fleet, decided not to flee but to attempt to stare Linois down. On February 15th, Dance order the brig Ganges and the four biggest East Indiamen to line up in battle formation and fly the blue ensigns of the Royal Navy. He was hoping to trick Linois into thinking the large merchant vessels were small warships, armed to the teeth and more than capable of defending the smaller merchant vessels against Linois’ one ship of the line and three frigates.

The ruse worked. Linois held back, unwilling to engage in battle until he was sure of what he was dealing with. Dance used the delay to return the fleet to sailing formation and make for the straits, but Linois’ warships were faster and began to nip at the heels of the slower, smaller merchant ships. Dance again made a daring choice, bringing the five lead ships about to face the French. Linois finally attacked, firing on the lead ship the Royal George. The other four, including the Warley, returned fire. In the confusion of the encounter, one of the other British ships crashed into the Warley leaving the two ships’ riggings entangled.

The ruse worked. Linois held back, unwilling to engage in battle until he was sure of what he was dealing with. Dance used the delay to return the fleet to sailing formation and make for the straits, but Linois’ warships were faster and began to nip at the heels of the slower, smaller merchant ships. Dance again made a daring choice, bringing the five lead ships about to face the French. Linois finally attacked, firing on the lead ship the Royal George. The other four, including the Warley, returned fire. In the confusion of the encounter, one of the other British ships crashed into the Warley leaving the two ships’ riggings entangled.

After an exchange of fire lasting less than an hour, Linois turned the French squadron around and fled. Dance, who obviously suffered no deficit of commitment, actually chased the French for two hours to make sure they didn’t turn around and attack them again. Then he reassembled the convoy that had gotten a little stretched thin and together they made their way to safety in the Straits of Malacca. They stayed anchored there for a couple of weeks until Royal Navy ships of the line arrived to escort them the rest of the way home.

Inman, acquitted himself admirably in this skirmish, commanding a team of Indian Lascar seamen armed with pikes. Once he was safe and sound in England, he returned to St John’s where in 1805 he got his MA and became a fellow of the College. The “odd little book” that with its owner had survived an encounter with the business end of French ships of the line and getting tangled in the rigging of a friendly ship, was donated to the College along with the rest of Inman’s collection of Chinese books.