This year marks the 500th anniversary of the death of Anne of Brittany, twice queen of France and the last ruler of an independent Brittany. Over the course of the year there will be a number of cultural events dedicated to the memory of this erudite and strong-willed duchess who fought her entire life for Breton independence with her body as the final battlefield.

This year marks the 500th anniversary of the death of Anne of Brittany, twice queen of France and the last ruler of an independent Brittany. Over the course of the year there will be a number of cultural events dedicated to the memory of this erudite and strong-willed duchess who fought her entire life for Breton independence with her body as the final battlefield.

That’s not entirely metaphoric either. Anne was her father Duke Francis II of Brittany’s only surviving heir. He tried desperately to marry her to someone anti-French to ensure the duchy would not end up annexed by France, but after he lost the Battle of Saint-Aubin-du-Cormier in 1488, he was forced to agree to a peace treaty that required the French king’s approval of Anne’s marriage. Francis died a month later, making Anne Duchess of Brittany at 11 years old.

Now obviously she had advisors — her father’s will left guardianship of her to John of Rieux, Marshal of Brittany, historian and diplomat Philippe, Count of Commines, and Anne’s governess Madame Laval — but even at so young an age she took the reins of power firmly in her own hands. When Anne of Beaujeau, regent for her brother King Charles VIII of France, took advantage of the child duchess’ perceived weakness and attacked Brittany, Anne reacted decisively. She appointed her most trusted councilors to government positions, convened the States General of Brittany, pawned her own jewelry to raise much-needed funds for the depleted treasury, minted viable coinage out of silver-tipped leather and called on the King of England, Henry VII, to help her fend off the French.

Now obviously she had advisors — her father’s will left guardianship of her to John of Rieux, Marshal of Brittany, historian and diplomat Philippe, Count of Commines, and Anne’s governess Madame Laval — but even at so young an age she took the reins of power firmly in her own hands. When Anne of Beaujeau, regent for her brother King Charles VIII of France, took advantage of the child duchess’ perceived weakness and attacked Brittany, Anne reacted decisively. She appointed her most trusted councilors to government positions, convened the States General of Brittany, pawned her own jewelry to raise much-needed funds for the depleted treasury, minted viable coinage out of silver-tipped leather and called on the King of England, Henry VII, to help her fend off the French.

The English turned out to be slow in sending help, but Austria and Spain sent troops to her aid. Meanwhile, the question of who she would marry became ever more pressing. Like her father, Anne cared first and foremost about which suitor could guarantee Breton independence. She did have her limits, though, and refused to marry Alain I, Lord of Albret, who had fought for Francis II against the French, because she considered him a scary brute (which by all accounts he was). Albret went into a rage at her refusal and sent troops to claim her by force. Anne, still a pre-teen at this point, met Albret’s forces head-on, mounting a horse and leading her archers against them.

That wouldn’t be the last time she took to the saddle to confront a bully. When she decided to accept the suit of Maximilian I of Austria, future Holy Roman Emperor, the man her father had wanted her to marry who she considered to be the strongest ally against France, Albret occupied Nantes and handed the castle over to the French. She and a small cadre of loyal barons (John of Rieux and Phillipe de Commines had sided with Albret because they believed he was the only hope for an independent Brittany) and some Spanish and German mercenaries rode up to the walls of Nantes and demanded they allow her entry as their sovereign. After two weeks of negotiations went nowhere, Anne’s party left only to be followed by Rieux and his soldiers. She stared him down too, turning around to face him and excoriate him for his disloyalty. Her bravery was so admired that Rieux let her go.

That wouldn’t be the last time she took to the saddle to confront a bully. When she decided to accept the suit of Maximilian I of Austria, future Holy Roman Emperor, the man her father had wanted her to marry who she considered to be the strongest ally against France, Albret occupied Nantes and handed the castle over to the French. She and a small cadre of loyal barons (John of Rieux and Phillipe de Commines had sided with Albret because they believed he was the only hope for an independent Brittany) and some Spanish and German mercenaries rode up to the walls of Nantes and demanded they allow her entry as their sovereign. After two weeks of negotiations went nowhere, Anne’s party left only to be followed by Rieux and his soldiers. She stared him down too, turning around to face him and excoriate him for his disloyalty. Her bravery was so admired that Rieux let her go.

The marriage to Maximilian did not solve her problems. France considered it a violation of the treaty since it was done without the approval of the king. Charles VIII besieged the city of Rennes and took it. Austria was of no help because Maximilian was busy fighting in Hungary. With France occupying four of Brittany’s main cities, Brittany’s nobles divided into two factions and money tight, Anne agreed to marry Charles. Since her marriage to Maximilian had been done by proxy (Maximilian sent an envoy to act in his lieu and they did this weird ceremonial thing where he put one bare knee on the bed to symbolize a consummation that never actually happened), it was easily annulled.

Marriage to Anne was the means by which Charles planned to finally take Brittany for France, if not in his lifetime then shortly thereafter. He put a clause in the marriage contract ensuring that whichever spouse outlived the other would rule Brittany. Just to cover all his bases, another clause stipulated that if he pre-deceased Anne, she would marry the next king of France, thereby giving France a second bite at the Brittany apple.

Marriage to Anne was the means by which Charles planned to finally take Brittany for France, if not in his lifetime then shortly thereafter. He put a clause in the marriage contract ensuring that whichever spouse outlived the other would rule Brittany. Just to cover all his bases, another clause stipulated that if he pre-deceased Anne, she would marry the next king of France, thereby giving France a second bite at the Brittany apple.

Married at 14, Anne would bear Charles seven children, none of whom survived, before he himself died when she was 21. As per the contract, she was to marry his heir, Louis XII, but he was already married. She told him she’d go through with it if he managed to get his marriage annulled within a year, then returned to Brittany and set about the business of ruling, something Charles had not allowed her to do when they were married. Much to Anne’s chagrin, Louis XII was able to get that annulment from Pope Alexander VI (aka Rodrigo Borgia) in exchange for some French estates for his son Cesare. Thus the Dowager Queen of France became Queen of France for a second time, the only woman ever to bear that distinction.

Anne of Brittany’s courts were centers of learning and art. She sponsored poets and scholars who introduced Renaissance humanism to France. She commissioned the first Renaissance style sculpture in France: the exceptionally beautiful tomb of her father, Francis II, and mother, Margaret of Foix, now in the Nantes Cathedral. The four cardinal virtues grace each corner of the tomb and the figure of Prudence bears Anne’s face. Four books of hours commissioned by her have survived, all of them masterpieces of illumination done after

Anne of Brittany’s courts were centers of learning and art. She sponsored poets and scholars who introduced Renaissance humanism to France. She commissioned the first Renaissance style sculpture in France: the exceptionally beautiful tomb of her father, Francis II, and mother, Margaret of Foix, now in the Nantes Cathedral. The four cardinal virtues grace each corner of the tomb and the figure of Prudence bears Anne’s face. Four books of hours commissioned by her have survived, all of them masterpieces of illumination done after print was already established in France. You can leaf through the Grandes Heures of Anne of Brittany on the Bibliothèque Nationale de France website, and it’s worth it for the incredibly accurate illuminations of 337 different plants in the page borders alone.

print was already established in France. You can leaf through the Grandes Heures of Anne of Brittany on the Bibliothèque Nationale de France website, and it’s worth it for the incredibly accurate illuminations of 337 different plants in the page borders alone.

Anne died desperately young of kidney stones just a few weeks short of her 37th birthday. She had at least seven more children with Louis, although only four survived their births and only two of them, daughters Claude and Renée, survived their mother. To her last breath she struggled against the seismic forces driving Brittany into French hands. With none of their male children surviving, Louis had betrothed Claude, Anne’s eldest daughter and heir, to his cousin and the heir to the French throne Francis of Angoulême. Anne knew that Claude’s inheritance and marriage would sound the death knell of Breton independence, so she left the duchy to her younger daughter Renée in her will, but Louis just ignored it.

A few months after Anne’s death, Claude and Francis married and a few months after that Louis died. Francis I was crowned on what would have been Anne’s 38th birthday. He made his and Claude’s son heir to the Duchy of Brittany and from then on, it was a province of France.

A few months after Anne’s death, Claude and Francis married and a few months after that Louis died. Francis I was crowned on what would have been Anne’s 38th birthday. He made his and Claude’s son heir to the Duchy of Brittany and from then on, it was a province of France.

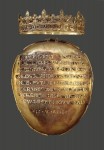

After her death, Anne was buried in the Basilica of Saint Denis, as was traditional for French sovereigns, but she left instructions in her will that her heart be removed and sent to Brittany. A beautiful gold reliquary was made to hold her heart, inscribed in old French with the following dedication: “In this little vessel of fine gold, pure and clean, rests a heart greater than any lady in the world ever had. Anne was her name, twice queen in France, Duchess of the Bretons, royal and sovereign.” It was first placed in her father’s tomb as she had willed and later moved to Saint Pierre Cathedral in Nantes.

The reliquary had a close brush with oblivion during the Revolution as part of the orgy of anti-monarchical destruction. In 1792 Anne’s heart was thrown away like so much trash and the reliquary ordered to be melted down. Thankfully it never happened. The artifact was kept in the Bibliothèque Nationale until in 1819 it was returned to Nantes. Its permanent home has been the Dobrée Museum since the late 19th century.

The reliquary had a close brush with oblivion during the Revolution as part of the orgy of anti-monarchical destruction. In 1792 Anne’s heart was thrown away like so much trash and the reliquary ordered to be melted down. Thankfully it never happened. The artifact was kept in the Bibliothèque Nationale until in 1819 it was returned to Nantes. Its permanent home has been the Dobrée Museum since the late 19th century.

Now the reliquary is ushering in Anne of Brittany season with an exhibition at the Royal Château of Blois where she died. The exhibition brings together the reliquary with contemporary descriptions and illuminations of her hugely elaborate 40-day funeral.