The only known surviving example of the first banknote issued in Australia will be going up for auction this month. The ten shilling note is conservatively estimated to sell for 250,000 Australian dollars ($225,000) and could well go for much higher considering its rarity and its excellent condition. It was found in a private collection in Scotland in 2005 and then acquired privately by another collector who is now selling it auction.

The only known surviving example of the first banknote issued in Australia will be going up for auction this month. The ten shilling note is conservatively estimated to sell for 250,000 Australian dollars ($225,000) and could well go for much higher considering its rarity and its excellent condition. It was found in a private collection in Scotland in 2005 and then acquired privately by another collector who is now selling it auction.

Issued by the Bank of New South Wales (now Westpac Banking Corporation after merging with the Commercial Bank of Australia Limited in 1982), this banknote is number 55 of one hundred ten shilling notes issued on the bank’s first day of business, April 8th, 1817. The bank was more than seven years in the making at that point. Lieutenant-Colonel Lachlan Macquarie had arrived in New South Wales at the end of 1809 to establish a functional government and economy in a colony in chaos. The New South Wales Corps, a local regiment that was supposed to maintain order was so corrupt it was known as the Rum Corps for its illegal control of the rum trade.

With the monetary system a jumble of ad hoc local currency, unreliable promissory notes and barter goods, Macquarie sought to stabilize the economy with standardized currency. He asked for permission from London authorities to establish a bank in the colony, but his request was rejected. In 1812, he took £10,000 in Spanish dollars Britain sent him and cleverly stretched them into Australia’s first official local currency by punching holes in them and creating the famous holey dollars (the donut-like outside of the coins) and the dumps (the center plugs).

With the monetary system a jumble of ad hoc local currency, unreliable promissory notes and barter goods, Macquarie sought to stabilize the economy with standardized currency. He asked for permission from London authorities to establish a bank in the colony, but his request was rejected. In 1812, he took £10,000 in Spanish dollars Britain sent him and cleverly stretched them into Australia’s first official local currency by punching holes in them and creating the famous holey dollars (the donut-like outside of the coins) and the dumps (the center plugs).

The holey dollars were in circulation from 1813 until 1822 and although they helped increase the amount of hard currency in the colony and prevent all the coin from leaving on trade ships, they were insufficient to alleviate New South Wales’ monetary woes and the unreliable promissory notes, barter and use of foreign currency continued. With London still dragging its feet, in 1816 Macquarie took matters into his own hands and forged ahead with a plan to found a colony bank. Capital was raised from 39 investors and 49 regulations adopted at a General Meeting of subscribers in February of 1817.

One of the regulations required that banknotes be issued in denominations of two shillings & sixpence, five shillings, 10 shillings, one pound and five pounds. To make the plates that would stamp these banknotes, the bank directors appointed Samuel Clayton, an Irish artist and silversmith who had been transported to New South Wales for forgery in 1816. (He wasn’t the only financial criminal to get a job producing money for the colony. William Henshall, who punched the dumps out of the holey dollars and overstamped both with their new values and mottos, had been transported for counterfeiting.)

One of the regulations required that banknotes be issued in denominations of two shillings & sixpence, five shillings, 10 shillings, one pound and five pounds. To make the plates that would stamp these banknotes, the bank directors appointed Samuel Clayton, an Irish artist and silversmith who had been transported to New South Wales for forgery in 1816. (He wasn’t the only financial criminal to get a job producing money for the colony. William Henshall, who punched the dumps out of the holey dollars and overstamped both with their new values and mottos, had been transported for counterfeiting.)

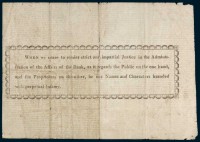

Since there was no banknote paper in New South Wales until 1820, to make the banknotes harder to forge Clayton inscribed legends on the back of the note with a unique letterpress. Number 55 is inscribed: “When we cease to render strict and impartial Justice in the Administration of the Affairs of the Bank, as it regards the Public on the one hand, and the Proprietors on the other, be our Names and Characters branded with perpetual Infamy.”

The governor signed the charter for the new bank on March 22nd, 1817, and, after a branch location was leased from Mrs. Mary Reibey, a successful businesswoman who herself had been transported to New South Wales for horse stealing in 1790 when she was just 13 years old, the Bank of New South Wales opened its doors at 10:00 AM, April 8th. The bank was a huge success, setting the colony off on a sturdy financial footing for the first time. Macquarie considered it the signature achievement of his governorship, later describing the founding of the bank as “the saving of the colony from ruin.”

The governor signed the charter for the new bank on March 22nd, 1817, and, after a branch location was leased from Mrs. Mary Reibey, a successful businesswoman who herself had been transported to New South Wales for horse stealing in 1790 when she was just 13 years old, the Bank of New South Wales opened its doors at 10:00 AM, April 8th. The bank was a huge success, setting the colony off on a sturdy financial footing for the first time. Macquarie considered it the signature achievement of his governorship, later describing the founding of the bank as “the saving of the colony from ruin.”

Unlike the bank, the delicate paper notes did not stand the test of time. Even the holey dollars are hard to come by these days with only 300 known to survive, and banknotes are obviously much harder used in circulation. How number 55 made it to Scotland is unknown, but it may have been brought there by Macquarie himself or at least one of his staff. He was Scottish and returned home after he resigned as governor of New South Wales in 1821.