So maybe the $7 flea market Renoir didn’t turn out to be the Antiques Roadshow-style fairy tale it seemed to be at first blush, but that story pales in comparison to the tale of an anonymous scrap metal dealer from an undisclosed Midwestern state who bought a gold egg clock at a flea market antiques stall for $14,000 and found out it was one of the eight lost Imperial Eggs made for the Tsar of All the Russias by jeweler Carl Fabergé.

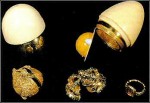

From 1885 to 1917, Fabergé made at least 50 Imperial Eggs for the Romanov emperors Alexander III and Nicholas II. Alexander started the tradition when he gave his beloved wife Empress Maria Feodorovna the Hen Egg for Easter in 1885. As a girl at the court of Denmark, Maria (formerly Princess Dagmar of Denmark) had been enchanted by an 18th century ivory egg owned by her aunt Princess Vilhelmine Marie of Denmark. Still in the Royal Danish Collection today, the egg screwed open to reveal a half yolk with a gold chicken inside, a diamond and gold crown inside the chicken and a diamond ring inside the crown. It’s not known whether Alexander III got the idea from that piece or if Fabergé did, but correspondence has survived indicating the Tsar was very much involved in the design of the first Imperial Egg. The Empress was thrilled by the charming white enameled egg that opened to reveal a whole gold yolk, a surprise gold chicken inside of the yolk, and a tiny replica of the Russian imperial crown inside of the chicken. Inside the crown hung a wee ruby pendant which could be attached to a gold chain and worn.

From 1885 to 1917, Fabergé made at least 50 Imperial Eggs for the Romanov emperors Alexander III and Nicholas II. Alexander started the tradition when he gave his beloved wife Empress Maria Feodorovna the Hen Egg for Easter in 1885. As a girl at the court of Denmark, Maria (formerly Princess Dagmar of Denmark) had been enchanted by an 18th century ivory egg owned by her aunt Princess Vilhelmine Marie of Denmark. Still in the Royal Danish Collection today, the egg screwed open to reveal a half yolk with a gold chicken inside, a diamond and gold crown inside the chicken and a diamond ring inside the crown. It’s not known whether Alexander III got the idea from that piece or if Fabergé did, but correspondence has survived indicating the Tsar was very much involved in the design of the first Imperial Egg. The Empress was thrilled by the charming white enameled egg that opened to reveal a whole gold yolk, a surprise gold chicken inside of the yolk, and a tiny replica of the Russian imperial crown inside of the chicken. Inside the crown hung a wee ruby pendant which could be attached to a gold chain and worn.

It was such a success that the gifting of an elaborate Fabergé Easter egg became an imperial tradition and its maker earned the title of official jewelry Supplier to the Imperial Court. They were recognized in their time as fabled wonders. Other aristocrats, wealthy industrialists and bankers commissioned eggs of their own from the jeweler, but the ones Fabergé made for the Tsars, uniquely intricate masterpieces crafted from the most precious materials, have become iconic symbols of the lavish Romanov court in the last years before its brutal demise.

It was such a success that the gifting of an elaborate Fabergé Easter egg became an imperial tradition and its maker earned the title of official jewelry Supplier to the Imperial Court. They were recognized in their time as fabled wonders. Other aristocrats, wealthy industrialists and bankers commissioned eggs of their own from the jeweler, but the ones Fabergé made for the Tsars, uniquely intricate masterpieces crafted from the most precious materials, have become iconic symbols of the lavish Romanov court in the last years before its brutal demise.

After the 1917 October Revolution, the Romanov palaces were ransacked. Some of the Imperial Eggs were lost during the looting, but most of them were inventoried, crated and stashed in the Kremlin Armory in Moscow. Lenin considered the Romanov treasures Russia’s cultural patrimony and ordered their preservation. Stalin, on the other hand, had no such scruples. He saw them as sources of hard currency, pure and simple, and between 1930 and 1933 14 Imperial eggs were sold in the West by Stalin’s commissars. He couldn’t sell all of them, though, because the Kremlin Armory curators risked their lives to hide the most important pieces.

Only one egg made it out of Russia still in Romanov hands. The Order of St. George Egg, which was made in 1916 as a gift from Tsar Nicholas II to his mother the Dowager Empress, was saved because she had moved to Kiev in 1916 as the situation at court grew more precarious. After her son’s abdication in March of 1917, she moved to Crimea where she managed to remain unmolested even as her son, daughter-in-law and grandchildren were shot to death. She refused to believe they were dead and she refused to leave Russia. Finally in 1919 her sister, Dowager Queen Alexandra of Britain, persuaded her to leave. King George V, who deeply regretted his decision not to rescue his cousin Nicky and his family in light of their horrible fate, sent the Iron Duke-class warship HMS Marlborough to pick her up at Yalta, and Maria fled carrying the egg and other treasures with her.

Only one egg made it out of Russia still in Romanov hands. The Order of St. George Egg, which was made in 1916 as a gift from Tsar Nicholas II to his mother the Dowager Empress, was saved because she had moved to Kiev in 1916 as the situation at court grew more precarious. After her son’s abdication in March of 1917, she moved to Crimea where she managed to remain unmolested even as her son, daughter-in-law and grandchildren were shot to death. She refused to believe they were dead and she refused to leave Russia. Finally in 1919 her sister, Dowager Queen Alexandra of Britain, persuaded her to leave. King George V, who deeply regretted his decision not to rescue his cousin Nicky and his family in light of their horrible fate, sent the Iron Duke-class warship HMS Marlborough to pick her up at Yalta, and Maria fled carrying the egg and other treasures with her.

Out of the 50 eggs, 42 were known to have survived in private collections and museums around the world. Eight were lost, and four of those were known only from their descriptions because there were no extant pictures. There has been some confusion in the scholarly community over the missing eggs, particularly when they were made and what they looked like. For many years experts thought the Blue Serpent Clock Egg, currently owned by Prince Albert II of Monaco, filled the 1887 spot on the timeline, but in fact it was made in 1885 and it’s one of those picture-less eggs, the Third Egg, that was gifted to Maria Feodorovna in 1887.

The Third Egg was photographed at the 1902 exhibition of Tsarina Alexandra’s and Dowager Empress Maria’s Fabergé treasures at the Von Dervis mansion in St. Petersburg, but it wasn’t until 2011 that it was identified in the Imperial Egg display vitrine thanks to the discovery of a more recent picture from 1964. It turns out that sometime after it was inventoried by Soviet curators in 1922, the Third Egg traveled west. In March of 1964 it was lot 259 in a Parke Bernet auction in New York, but it was not identified as an Imperial Egg. It wasn’t even identified as a Fabergé. From the catalog:

The Third Egg was photographed at the 1902 exhibition of Tsarina Alexandra’s and Dowager Empress Maria’s Fabergé treasures at the Von Dervis mansion in St. Petersburg, but it wasn’t until 2011 that it was identified in the Imperial Egg display vitrine thanks to the discovery of a more recent picture from 1964. It turns out that sometime after it was inventoried by Soviet curators in 1922, the Third Egg traveled west. In March of 1964 it was lot 259 in a Parke Bernet auction in New York, but it was not identified as an Imperial Egg. It wasn’t even identified as a Fabergé. From the catalog:

Gold Watch in Egg-Form Case on Wrought Three-Tone Gold Stand, Set with Jewels

Fourteen-karat gold watch in reeded egg-shaped case with seventy-five point old-mine diamond clasp by Vacheron & Constantin; on eighteen-karat three-tone gold stand exquisitely wrought with an annulus, bordered with wave scrollings and pairs of corbel-like legs ciselé with a capping of roses, pendants of tiny leaves depending to animalistic feet with ring stretcher; the annulus bears three medallions of cabochon sapphires surmounted by tiny bowknotted ribbons set with minute diamonds, which support very finely ciselé three-tone gold swags of roses and leaves which continue downward and over the pairs of legs. Height 3 1/4 inches.

The disinherited Imperial Egg was purchased at that auction by a Southern lady for $2450. After her death in the early 2000s, her estate was sold and the egg, still unrecognized, made its way to a midwestern antiques stall where it was spotted by a scrap metal dealer. He planned to quickly resell it to be melted down for its gold value, but all of the prospective buyers who tested it thought he had overpaid. Blessedly stubborn, he refused to sell it at a loss and so for years he just kept the egg at home.

The disinherited Imperial Egg was purchased at that auction by a Southern lady for $2450. After her death in the early 2000s, her estate was sold and the egg, still unrecognized, made its way to a midwestern antiques stall where it was spotted by a scrap metal dealer. He planned to quickly resell it to be melted down for its gold value, but all of the prospective buyers who tested it thought he had overpaid. Blessedly stubborn, he refused to sell it at a loss and so for years he just kept the egg at home.

In 2012, he Googled “egg” and the only name he could find on the piece “Vacheron Constantin,” the makers of the lady’s watch that was the surprise inside. The results pointed him to a fateful article in the Telegraph that had been written in 2011 when the auction photograph of the Third Egg was discovered. “Is this £20 million nest-egg on your mantelpiece?” was the incredibly fortuitous headline, and the scrap metal fellow kind of thought his answer to the question might be yes.

In 2012, he Googled “egg” and the only name he could find on the piece “Vacheron Constantin,” the makers of the lady’s watch that was the surprise inside. The results pointed him to a fateful article in the Telegraph that had been written in 2011 when the auction photograph of the Third Egg was discovered. “Is this £20 million nest-egg on your mantelpiece?” was the incredibly fortuitous headline, and the scrap metal fellow kind of thought his answer to the question might be yes.

He contacted the expert cited in the article, Kieran McCarthy of London jewelers and Fabergé specialists Wartski, and the rest is history that reads like a fairy tale.

Mr McCarthy said: “He saw the article and recognised his egg in the picture. He flew straight over to London – the first time he had ever been to Europe – and came to see us. He hadn’t slept for days.

“He brought pictures of the egg and I knew instantaneously that was it. I was flabbergasted – it was like being Indiana Jones and finding the Lost Ark.”

Mr McCarthy flew to the US to verify the discovery.

“It was a very modest home in the Mid West, next to a highway and a Dunkin’ Donuts. There was the egg, next to some cupcakes on the kitchen counter.

“I examined it and said, ‘You have an Imperial Fabergé Easter Egg.’ And he practically fainted. He literally fell to the floor in astonishment.” The dealer etched Mr McCarthy’s name and the date into the wooden bar stool on which Mr McCarthy sat to examine the egg, marking the day that his life changed forever.

Wartski immediately arranged a private sale of the egg for an undisclosed sum that is certainly in the tens of millions. Russian oligarch Victor Vekselberg spent $100 million buying nine Imperial eggs from the estate of Malcolm Forbes in 2004, and in 2007 a non-Imperial egg sold at auction for $18.5 million. There are scratches on the surface of the egg from where would-be buyers sampled the material to test its gold content, but they didn’t decrease its market value. They might have even increased it, since they’re a record of this stranger-than-fiction backstory.

The scrap metal dealer, petrified that people will find out he hit the decorative arts Powerball, has limited himself to purchasing a new car and a new house just down the road from his old house. The new owner has allowed Wartski to exhibit the Third Egg at their Mayfair store from April 14th to 17th, 112 years after it was last seen in public under its true identity.