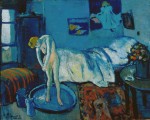

Infrared imaging confirmed what experts have long suspected about Pablo Picasso’s 1901 work The Blue Room: there’s a whole other painting underneath, a portrait of a bearded man in a bow tie. A conservator at The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., which has owned the painting since 1927, first noted that the brushwork was atypical in 1954. X-rays in the 1990s confirmed that there appeared to be something underneath The Blue Room, but it wasn’t until 2008 that infrared imaging revealed a clear picture of a bearded man in a bow tie and jacket resting his head on his hand, and the revelation wasn’t announced until now.

Infrared imaging confirmed what experts have long suspected about Pablo Picasso’s 1901 work The Blue Room: there’s a whole other painting underneath, a portrait of a bearded man in a bow tie. A conservator at The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., which has owned the painting since 1927, first noted that the brushwork was atypical in 1954. X-rays in the 1990s confirmed that there appeared to be something underneath The Blue Room, but it wasn’t until 2008 that infrared imaging revealed a clear picture of a bearded man in a bow tie and jacket resting his head on his hand, and the revelation wasn’t announced until now.

“It’s really one of those moments that really makes what you do special,” said Patricia Favero, the conservator at The Phillips Collection who pieced together the best infrared image yet of the man’s face.

“The second reaction was, ‘Well, who is it?’ We’re still working on answering that question.”

Scholars have ruled out the possibility that it was a self-portrait. One possible figure is the Paris art dealer Ambroise Vollard, who hosted Picasso’s first show in 1901. But there’s no documentation and no clues left on the canvas, so the research continues.

Picasso made several portraits of Vollard, a highly influential figure in the art world of late 19th, early 20th century Paris. He was a great supporter of the likes of Vincent van Gogh, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin, and the young Picasso was eager to join the dealer’s roster of talent. Vollard loved to sit for his artists, and Picasso knew it would behoove him to flatter his vanity. He would pursue a contract with Vollard for decades, but although Vollard was glad to buy and sell individual pieces, Picasso never did secure his services as his primary dealer.

Picasso made several portraits of Vollard, a highly influential figure in the art world of late 19th, early 20th century Paris. He was a great supporter of the likes of Vincent van Gogh, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin, and the young Picasso was eager to join the dealer’s roster of talent. Vollard loved to sit for his artists, and Picasso knew it would behoove him to flatter his vanity. He would pursue a contract with Vollard for decades, but although Vollard was glad to buy and sell individual pieces, Picasso never did secure his services as his primary dealer.

In 1901 when Picasso had his first show at Vollard’s gallery on rue Lafitte, the artist was just 19 years old. That show was full of color and vibrant themes, for instance Crazy Woman with Cats. Vollard considered the showing a failure with many works left unsold. Picasso’s art took a drastic turn that year as he launched into his now-famous Blue Period. Influenced by Gaugin and Toulouse-Lautrec and his own depression after the suicide of his friend Carlos Casagemas, Picasso chose subjects that emphasized human misery — the elderly, infirm, prostitutes, beggars, drunks — with the color blue dominating the works. The Parisian critics and buyers weren’t fans at first. Vollard himself didn’t start buying Blue Period paintings until 1906, two years after the period’s end, and then only because influential collectors Leo and Gertrude Stein had begun to collect them.

In 1901 when Picasso had his first show at Vollard’s gallery on rue Lafitte, the artist was just 19 years old. That show was full of color and vibrant themes, for instance Crazy Woman with Cats. Vollard considered the showing a failure with many works left unsold. Picasso’s art took a drastic turn that year as he launched into his now-famous Blue Period. Influenced by Gaugin and Toulouse-Lautrec and his own depression after the suicide of his friend Carlos Casagemas, Picasso chose subjects that emphasized human misery — the elderly, infirm, prostitutes, beggars, drunks — with the color blue dominating the works. The Parisian critics and buyers weren’t fans at first. Vollard himself didn’t start buying Blue Period paintings until 1906, two years after the period’s end, and then only because influential collectors Leo and Gertrude Stein had begun to collect them.

Another possible candidate for the sitter of the hidden portrait is Spanish writer Pío Baroja. He published his first novel in 1900, and Picasso is known to have drawn him for an issue of Arte Joven (Young Art), a magazine Picasso co-founded with his friend Francisco de Asís Soler in Madrid in early 1901 which published only five issues before folding in June.

Another possible candidate for the sitter of the hidden portrait is Spanish writer Pío Baroja. He published his first novel in 1900, and Picasso is known to have drawn him for an issue of Arte Joven (Young Art), a magazine Picasso co-founded with his friend Francisco de Asís Soler in Madrid in early 1901 which published only five issues before folding in June.

Based solely on the timing and the beard, I’d propose fellow artist Jaume Andreu Bonsons as a possible subject. There’s a drawing of the two of them Picasso did upon his return to Paris in late winter, early spring of 1901 (nobody is quite sure when he returned to Paris from Spain that year). Tenuous, I know, but what the hell, right? You can tweet any ideas you have to the Phillips Collection, #BlueRoom, or comment on their blog.

Based solely on the timing and the beard, I’d propose fellow artist Jaume Andreu Bonsons as a possible subject. There’s a drawing of the two of them Picasso did upon his return to Paris in late winter, early spring of 1901 (nobody is quite sure when he returned to Paris from Spain that year). Tenuous, I know, but what the hell, right? You can tweet any ideas you have to the Phillips Collection, #BlueRoom, or comment on their blog.

The Blue Room is on tour in South Korea through early 2015, but research proceeds apace. Conservators plan to employ additional imaging technology to attempt to identify the colors used in the portrait. In 2017, the painting will be the centerpiece of a new exhibit that will cover both The Blue Room and the bearded gent beneath it.

The Blue Room is on tour in South Korea through early 2015, but research proceeds apace. Conservators plan to employ additional imaging technology to attempt to identify the colors used in the portrait. In 2017, the painting will be the centerpiece of a new exhibit that will cover both The Blue Room and the bearded gent beneath it.