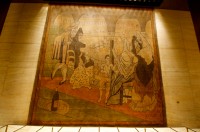

The biggest Picasso in the United States will be leaving its home on a wall at the Four Seasons restaurant in New York for what one hopes will be greener pastures at the New York Historical Society. RFR Holding, owner of the historic Seagram Building where the Four Seasons and the 19-by-20-foot theatrical curtain have lived together in harmony since 1957, planned to remove the work last year. It claimed the wall on which it hung was structurally unsound due to a leaking steam pipe and informed the New York Landmarks Conservancy, owner of the painting since it was donated to it by Vivendi Universal, then owner of the Seagram Building, in 2005, that the curtain would be coming down immediately.

The biggest Picasso in the United States will be leaving its home on a wall at the Four Seasons restaurant in New York for what one hopes will be greener pastures at the New York Historical Society. RFR Holding, owner of the historic Seagram Building where the Four Seasons and the 19-by-20-foot theatrical curtain have lived together in harmony since 1957, planned to remove the work last year. It claimed the wall on which it hung was structurally unsound due to a leaking steam pipe and informed the New York Landmarks Conservancy, owner of the painting since it was donated to it by Vivendi Universal, then owner of the Seagram Building, in 2005, that the curtain would be coming down immediately.

The Conservancy challenged the plan in court. They said the curtain was far too fragile to be moved, especially by rolling the canvas up “one click at a time” and transporting it in a rental van. At the last minute, the court sided with the Conservancy and issued a temporary restraining order. Since then, RFR Holding and the Landmarks Conservancy have been locked in a struggle over the fate of the historical curtain. The discussions have now apparently borne fruit, and the front cloth painted by Pablo Picasso in 1919 for a production of the Ballets Russes’ Le Tricorne will be moved to the New York Historical Society, conserved and put on display, all at RFR’s expense.

To move the Picasso, workers will mount hydraulic lifts to detach the top of the curtain from the wall. It will then be wrapped around a wide roller, starting at the bottom. The curtain will first go to a conservator, for cleaning and restoration work. The historical society plans to have it installed for an exhibition in May.

That process sounds a lot like the original “one click at a time” plan which the Conservancy deemed far too dangerous. The art mover agreed that the painting could “crack like a potato chip” under the strain. The Conservancy isn’t too thrilled about it, judging from their press release, but they will have conservators on the ground during the removal and transport stages.

The impetus for this compromise is the looming defeat in court the Conservancy expected. The donation was made on the condition that the curtain remain where it was at the Four Seasons, but that wasn’t going to be able to trump RFR’s solid legal position. From the Landmarks Conservancy press release:

The impetus for this compromise is the looming defeat in court the Conservancy expected. The donation was made on the condition that the curtain remain where it was at the Four Seasons, but that wasn’t going to be able to trump RFR’s solid legal position. From the Landmarks Conservancy press release:

We did our best to maintain it in place. But our only leverage was that the Curtain is specifically included in the current restaurant lease. It was made clear to us that the Curtain would not be included in whatever new lease is negotiated. So, if we had prevailed in Court, the most a judge could grant is that the Curtain stay until the end of the current lease.

Phyllis Lambert, daughter of Seagram founder Samuel Bronfman, purchased and installed the curtain in 1957. She’s not in favor of this plan.

“It sort of breaks my heart,” she said.

Vivendi bought the Seagram company, including its large art collection, in 2000, around the time Mr. Rosen bought the Seagram Building. Later, the financially ailing Vivendi moved to sell the entire Seagram art collection, but Ms. Lambert persuaded Vivendi to bequeath the Picasso to the conservancy.

Lambert has every reason to be bummed. The curtain is an iconic part of what has become a beloved and famous interior. However, the Conservancy had few options here, and it’s undoubtedly better for its long-term prospects for the painting to be in the hands of a museum instead of a company owned by a man who once called the curtain a “schmatte” (Yiddish for “rag”) and who appears to be keen to install works from his own modern art collection in the space. The pressing issue is how to ensure the least possible trauma in the removal and transportation.

The New York Historical Society is thrilled to have it. They plan to make Le Tricorne the centerpiece of the second-floor gallery.