The enamelled bronze cockerel found in a child’s grave in the western cemetery of Roman Cirencester in 2011 has gone on display at the Corinium Museum along with other artifacts excavated during that dig. The site was known to have had a Roman cemetery since the 1960s when it was surveyed before the construction of Bridges Garage, but the auto body shop had dug deep to accommodate two huge underground fuel tanks, so archaeologists thought whatever was left of the cemetery was probably destroyed.

The enamelled bronze cockerel found in a child’s grave in the western cemetery of Roman Cirencester in 2011 has gone on display at the Corinium Museum along with other artifacts excavated during that dig. The site was known to have had a Roman cemetery since the 1960s when it was surveyed before the construction of Bridges Garage, but the auto body shop had dug deep to accommodate two huge underground fuel tanks, so archaeologists thought whatever was left of the cemetery was probably destroyed.

When the Bridges Garage property was slated for redevelopment in 2011, the archaeologists who returned to survey the site had modest expectations. Much to their surprise, they found 71 inhumations and  three cremations, a surprisingly high number of the former (the 60s excavation had found 46 cremations and eight inhumations). The cemetery spanned almost the entire period of Roman Britain, from the late 1st century through the fourth. Archaeologists were able to identify 30 females and 21 males from the inhumations (the sex of the remaining 20 could not be determined). There was significantly more bone wear in the shoulders of the male, probably an indication of repetitive motion strain from skilled crafts like stone-working rather than agricultural work.

three cremations, a surprisingly high number of the former (the 60s excavation had found 46 cremations and eight inhumations). The cemetery spanned almost the entire period of Roman Britain, from the late 1st century through the fourth. Archaeologists were able to identify 30 females and 21 males from the inhumations (the sex of the remaining 20 could not be determined). There was significantly more bone wear in the shoulders of the male, probably an indication of repetitive motion strain from skilled crafts like stone-working rather than agricultural work.

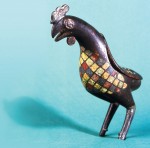

The grave in which the cockerel was found is one of the earlier ones, dating to the middle of the 2nd century A.D. The child was about two or three years old and must have come from a wealthy family because she or he was buried in a wooden coffin with the bronze cockerel placed near his head and a pottery feeding cup with a drinking spout known as a tettine. The cockerel was a very expensive piece, the product of high quality workmanship made in northern Britain and exported all over the empire.

The grave in which the cockerel was found is one of the earlier ones, dating to the middle of the 2nd century A.D. The child was about two or three years old and must have come from a wealthy family because she or he was buried in a wooden coffin with the bronze cockerel placed near his head and a pottery feeding cup with a drinking spout known as a tettine. The cockerel was a very expensive piece, the product of high quality workmanship made in northern Britain and exported all over the empire.

Only eight of these objects survive, four in Britain, four in Germany and the Low Countries. This is the only one of the British cockerels to have been found in a grave, and the only one of all of them that still has its tail. That’s significant not just because it’s a fabulous openwork enameled rooster tail, but because before it was found, archaeologists speculated that these figurines might have had a practical use, like as lamps, due to their hollow bodies. The tail was soldered in place, however, making the hollow body inaccessible and usage as a lamp impossible. It was likely included in the grave as a symbol of the god Mercury who guided the souls of the dead to the afterlife.

Only eight of these objects survive, four in Britain, four in Germany and the Low Countries. This is the only one of the British cockerels to have been found in a grave, and the only one of all of them that still has its tail. That’s significant not just because it’s a fabulous openwork enameled rooster tail, but because before it was found, archaeologists speculated that these figurines might have had a practical use, like as lamps, due to their hollow bodies. The tail was soldered in place, however, making the hollow body inaccessible and usage as a lamp impossible. It was likely included in the grave as a symbol of the god Mercury who guided the souls of the dead to the afterlife.

In the same display case with the cockerel are a selection of jewels also found in the grave of a child. Jet beads found around the neck were once part of a necklace. Jet bracelets and bangles were found at the wrists, while two bronze bracelets were buried under the child’s feet. This was a later burial than the cockerel child’s, dating to the late 3rd or early 4th century. Other jewels on display were found in the grave of a late Roman woman. Near her wrist archaeologists found bone bracelets with metal clasps, a sheet metal bracelet with abstract designs and a bracelet of glass and bone beads strung on a copper-alloy wire chain.

In the same display case with the cockerel are a selection of jewels also found in the grave of a child. Jet beads found around the neck were once part of a necklace. Jet bracelets and bangles were found at the wrists, while two bronze bracelets were buried under the child’s feet. This was a later burial than the cockerel child’s, dating to the late 3rd or early 4th century. Other jewels on display were found in the grave of a late Roman woman. Near her wrist archaeologists found bone bracelets with metal clasps, a sheet metal bracelet with abstract designs and a bracelet of glass and bone beads strung on a copper-alloy wire chain.