First Darwin’s barnacles turned up in the University of Copenhagen’s Natural History Museum. Now the Natural History Museum in London has discovered a collection of previously unknown beetle specimens gathered by Dr. David Livingstone during his Zambezi expedition of 1858–64. These are the only known surviving specimens collected by Livingstone on the chaotic history-making expedition to open up the Zambezi River to English trade and resource exploitation. Impassable rapids and waterfalls ensured his utter failure on that score, but the expedition was the first to reach and explore Lake Malawi.

First Darwin’s barnacles turned up in the University of Copenhagen’s Natural History Museum. Now the Natural History Museum in London has discovered a collection of previously unknown beetle specimens gathered by Dr. David Livingstone during his Zambezi expedition of 1858–64. These are the only known surviving specimens collected by Livingstone on the chaotic history-making expedition to open up the Zambezi River to English trade and resource exploitation. Impassable rapids and waterfalls ensured his utter failure on that score, but the expedition was the first to reach and explore Lake Malawi.

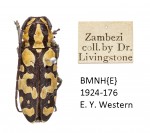

The specimens were discovered by Max Barclay, the Natural History Museum’s Collections Manager of Coleoptera and Hymenoptera. He was doing a check of the museum’s vast stores as part of an effort to catalog some of the collection online when he found a wooden box containing 20 pinned beetles neatly labeled “Zambezi coll. by Dr. Livingstone.”

The specimens were discovered by Max Barclay, the Natural History Museum’s Collections Manager of Coleoptera and Hymenoptera. He was doing a check of the museum’s vast stores as part of an effort to catalog some of the collection online when he found a wooden box containing 20 pinned beetles neatly labeled “Zambezi coll. by Dr. Livingstone.”

Max Barclay comments, “The Natural History Museum holds one of the largest, oldest and most comprehensive collections of its kind, consulted every year by hundreds of scientists from all over the world. The beetle collection alone includes almost 10 million specimens, assembled over centuries. To study them all will take a lifetime. I have worked here for more than 10 years and it was a complete surprise and incredibly exciting to find these well preserved beetles, brought back from Africa 150 years ago almost to the day. These specimens are still valuable to science. Museum researchers use historical specimens to study the effect of changing environments on plants and animals around the world.”

The beetles were a bequest by Edward Young Western, a lawyer and dedicated amateur entomologist who left a large collection of 15,000 insect specimens to the Natural History Museum after his death in 1924. Museum researchers believe he acquired the box of beetles from one of the members of Livingstone’s expedition, perhaps Livingstone’s own brother Charles. The expedition had been funded by the government and David Livingstone considered all material collected to be government property, so the sale of these specimens had to be done on the quiet. Experts believe they were sold at a natural history auction in the 1860s.

The beetles were a bequest by Edward Young Western, a lawyer and dedicated amateur entomologist who left a large collection of 15,000 insect specimens to the Natural History Museum after his death in 1924. Museum researchers believe he acquired the box of beetles from one of the members of Livingstone’s expedition, perhaps Livingstone’s own brother Charles. The expedition had been funded by the government and David Livingstone considered all material collected to be government property, so the sale of these specimens had to be done on the quiet. Experts believe they were sold at a natural history auction in the 1860s.

They were easier to dispose of quietly because the specimens were never published. Although the Zambezi Expedition was considered an abject failure due to its escalating costs, high body count (David’s wife Mary died of malaria shortly after she joined her husband at Lake Malawi in 1862), prodigious rate of personnel being fired or quitting and, most importantly to the government, its failure to find a navigable river route to the interior, the scientific exploration was very successful. Physician and naturalist John Kirk (left the expedition in 1863), physician and botanist Charles James Meller and geologist Richard Thornton (fired by Livingstone) collected a great many specimens for study.

In David and Charles Livingstone’s Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambesi, published in 1866, two years after the expedition was recalled, they laud John Kirk’s collecting work in particular, noting that he’s not listed as a co-author solely because they hope he will publish his own record.

In David and Charles Livingstone’s Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambesi, published in 1866, two years after the expedition was recalled, they laud John Kirk’s collecting work in particular, noting that he’s not listed as a co-author solely because they hope he will publish his own record.

He [Dr. Kirk] collected above four thousand species of plants, specimens of most of the valuable woods, of the different native manufactures, of the articles of food, and of the different kinds of cotton from every spot we visited, and a great variety of birds and insects, besides making meteorological observations, and affording, as our instructions required, medical assistance to the natives in every case where he could be of any use.

Charles Livingstone was also fully occupied in his duties in following out the general objects of our mission, in encouraging the culture of cotton, in making many magnetic and meteorological observations, in photographing so long as the materials would serve, and in collecting a large number of birds, insects, and other objects of interest The collections, being government property, have been forwarded to the British Museum and to the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew; and, should Dr. Kirk undertake their description, three or four years will be required for the purpose.

Many of the new mammal, reptile and avian species found on the expedition were published in scientific journals and were very well received, but for some reason, the insects were neglected, leaving a hole through which 20 beetles could slip through into Edward Young Western’s hands. Because the Natural History Museum has such a massive insect collection, Livingstone’s beetles joined the teeming masses without anybody noticing.

Many of the new mammal, reptile and avian species found on the expedition were published in scientific journals and were very well received, but for some reason, the insects were neglected, leaving a hole through which 20 beetles could slip through into Edward Young Western’s hands. Because the Natural History Museum has such a massive insect collection, Livingstone’s beetles joined the teeming masses without anybody noticing.