Before Howard Carter became the world-famous archaeologist who discovered the tomb of King Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings, he was an artist. In fact, it was pretty much all he knew how to do. Howard, the youngest of 11 children of Samuel and Martha Carter, was sick a lot in his youth. The many and varied miasmas of London were considered injurious to his health, so he was sent to live with his aunts in Swaffham, Norfolk, where his father and grandfather had been gamekeepers on the Hamond family estate.

Before Howard Carter became the world-famous archaeologist who discovered the tomb of King Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings, he was an artist. In fact, it was pretty much all he knew how to do. Howard, the youngest of 11 children of Samuel and Martha Carter, was sick a lot in his youth. The many and varied miasmas of London were considered injurious to his health, so he was sent to live with his aunts in Swaffham, Norfolk, where his father and grandfather had been gamekeepers on the Hamond family estate.

Because of his sickliness he was never enrolled in school. His father, an artist who carved out a successful niche for himself painting portraits of the gentry and their pets, tutored Howard on regular trips to Swaffham, teaching him how to draw and paint. One of Samuel Carter’s patrons was William Amherst Tyssen-Amherst of Didlington Hall, an estate eight miles from Swaffham. As a boy, Howard visited Didlington Hall when his father painted Lord Amherst’s portrait, and this is where he first became exposed to Egyptology.

Amherst was an avid collector of Egyptian antiquities. He, his wife Margaret Mitford (whose father had a passion for all things Egyptian as well) and their seven daughters traveled frequently to Egypt, constantly acquiring new artifacts. A whole wing of Didlington Hall was dedicated to housing his vast collection. Seven statues of the lion-headed warrior goddess Sekhmet guarded the door of the museum, one for each of the Amherst daughters. Those statues are now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Amherst was an avid collector of Egyptian antiquities. He, his wife Margaret Mitford (whose father had a passion for all things Egyptian as well) and their seven daughters traveled frequently to Egypt, constantly acquiring new artifacts. A whole wing of Didlington Hall was dedicated to housing his vast collection. Seven statues of the lion-headed warrior goddess Sekhmet guarded the door of the museum, one for each of the Amherst daughters. Those statues are now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Amherst family didn’t just give Howard Carter the chance to explore Egyptian art through their extensive collection. It was their recommendation and contacts that secured him his first job in Egypt. He was just 17 years old when he was hired as a tracer — someone who copies inscriptions and art work found in excavations onto paper for later study — for the Egyptian Exploration Fund (EEF) in 1891. This was an essential job in the age before color photography. Watercolors were the only accurate recreations of tomb decorations available.

Carter’s first assignment was the Beni Hasan excavation where the princes of Middle Egypt were buried. He immediately distinguished himself with his artistic ability and dedication, often working all day and then spending the night in the tomb. Carter began to learn archaeology on his next assignment at El-Amarna under pioneering Egyptologist Flinders Petrie in 1892. He was still an artist, recording artifacts as they were discovered, but Petrie allowed him to dig too, and Carter made some signficant finds.

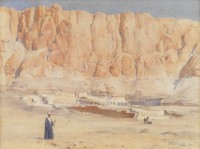

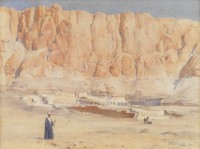

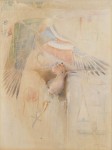

In 1894, Carter was appointed Principle Artist of the EEF’s excavation of the Temple of Queen Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari. For five years Carter made drawings and watercolors of the wall reliefs in the temple. One of his watercolors from this period, The Temple of Hatshepsut (1899), is going up for auction at Bonhams’ Travel, Exploration and Natural History Sale in London on December 3rd.

In 1894, Carter was appointed Principle Artist of the EEF’s excavation of the Temple of Queen Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari. For five years Carter made drawings and watercolors of the wall reliefs in the temple. One of his watercolors from this period, The Temple of Hatshepsut (1899), is going up for auction at Bonhams’ Travel, Exploration and Natural History Sale in London on December 3rd.

Carter also joined in the excavation of the temple and learned restoration techniques as well. He did such a fine job that in 1899 the Egyptian Antiquities Service offered him the job of First Chief Inspector General of Monuments for Upper Egypt. He was 25 years old, had no formal education, and was now the supervisor of all archaeological excavations in the Upper Nile Valley. Carter did great work, installing the first electric lights in six Valley of the Kings tombs and at the temples in Abu Simbel.

His extraordinary run of success came to a halt in 1905 when a group of drunk and belligerent French tourists became violent towards the Egyptian guards at Saqqara. Carter told the guards they could defend themselves. The tourists complained to people in high places and the diplomatic hotshots insisted Carter apologize. He refused. In retaliation, Carter was shipped off to an obscure site with not much in the way of archaeology. Rather than twiddle his thumbs in exile, Carter resigned.

For the next two years, Howard Carter had something of a hard scrabble existence. He sold his watercolors or guided tours to make a living. Then he hit the jackpot. French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero, Director of the Egyptian Antiquities Service who had given Carter the Chief Inspector General job, introduced him to George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon. Carnarvon had deep pockets and was keen to fund archaeological excavations. He got the necessary licenses and made Carter the Supervisor of Excavations in Thebes.

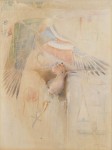

During this time, Carter painted Under the Protection of the Gods (1908), a composite fantasy that depicts a vulture — representing the goddess Nekhebet, protector of Upper Egypt — above a solar disc wrapped in a cobra — representing the goddess Wadjet, protector of Lower Egypt. It’s likely that the iconography of the watercolor was inspired by some of Carter’s finds in Thebes, including the 18th Dynasty Tomb of Tetaki and a 15th Dynasty tomb with nine coffins.

During this time, Carter painted Under the Protection of the Gods (1908), a composite fantasy that depicts a vulture — representing the goddess Nekhebet, protector of Upper Egypt — above a solar disc wrapped in a cobra — representing the goddess Wadjet, protector of Lower Egypt. It’s likely that the iconography of the watercolor was inspired by some of Carter’s finds in Thebes, including the 18th Dynasty Tomb of Tetaki and a 15th Dynasty tomb with nine coffins.

The Carter-Carnarvon partnership was very successful. By the time World War I began in 1914, Carnarvon had amassed a hugely important collection of Egyptian antiquities. That same year he secured a 15-year license to excavate the Valley of the Kings and Carter got to work. He painted The Valley of the Kings (1914) the first year of excavations. Excavations were disrupted by war, but Carter still managed to dig in 1915 and 1917.

In 1918 excavations restarted in earnest. For the next four years, Carter scoured the Valley of the Kings for the tomb of a previously unknown pharaoh whose name he had discovered. It became something of an obsession with him, but in 1922 when the tomb continued to be elusive, Carnarvon got sick of funding what seemed like a fool’s errand and told Carter that he had one digging season left. Three days after the last excavation began in November of 1922, Carter’s diggers found the top of a staircase. Three weeks later, Carter peered in through a small hole in the doorway and saw the “wonderful things,” that would take the world by storm and make him immortal.

In 1918 excavations restarted in earnest. For the next four years, Carter scoured the Valley of the Kings for the tomb of a previously unknown pharaoh whose name he had discovered. It became something of an obsession with him, but in 1922 when the tomb continued to be elusive, Carnarvon got sick of funding what seemed like a fool’s errand and told Carter that he had one digging season left. Three days after the last excavation began in November of 1922, Carter’s diggers found the top of a staircase. Three weeks later, Carter peered in through a small hole in the doorway and saw the “wonderful things,” that would take the world by storm and make him immortal.

Carter never forgot the people who helped him overcome his humble beginnings. His connection with the Amherst family continued throughout his life. William and Margaret Amherst’s eldest daughter Mary, known as May, wife of Lord William Cecil, took her family’s fascination with Egypt to even greater heights. Between 1901 and 1904, she personally funded and ran excavations at Qubbet el-Hawa in Aswan. Howard Carter was Chief Inspector for Antiquities then, and he helped advise her.

In 1906, the family was left financially devastated when their solicitor and land agent, Charles Cheston, was found to have embezzled hundreds of thousand of pounds to support his gambling habit. Cheston committed suicide. Lord Amherst was forced to sell the collections he had spent decades building into some of the greatest private holdings in the country. His library went first, auctioned by Sotheby’s in 1908 and 1909. William Amherst died two months before the second sale.

In 1906, the family was left financially devastated when their solicitor and land agent, Charles Cheston, was found to have embezzled hundreds of thousand of pounds to support his gambling habit. Cheston committed suicide. Lord Amherst was forced to sell the collections he had spent decades building into some of the greatest private holdings in the country. His library went first, auctioned by Sotheby’s in 1908 and 1909. William Amherst died two months before the second sale.

May, heir to her father’s estate and title, had no choice but to continue the sell-off. In 1910, the estate itself, home and park, was sold to Colonel Herbert Francis Smith. May refused to sell her father’s Egyptian collection, however. She held on to that resolutely for a decade until her death from breast cancer in 1919. Only after May was gone was the legendary Amherst collection of Egyptian papyri, statues and other artifacts put up for sale at Sotheby’s in 1921. It was Howard Carter who catalogued the collection that had first inspired his great vocation. At the time of the sale, even though some individual objects had been sold piecemeal before then, the Amherst Egyptian collection was the third largest private collection in England.

May, heir to her father’s estate and title, had no choice but to continue the sell-off. In 1910, the estate itself, home and park, was sold to Colonel Herbert Francis Smith. May refused to sell her father’s Egyptian collection, however. She held on to that resolutely for a decade until her death from breast cancer in 1919. Only after May was gone was the legendary Amherst collection of Egyptian papyri, statues and other artifacts put up for sale at Sotheby’s in 1921. It was Howard Carter who catalogued the collection that had first inspired his great vocation. At the time of the sale, even though some individual objects had been sold piecemeal before then, the Amherst Egyptian collection was the third largest private collection in England.

In 1950, Didlington Hall, broken and neglected after requisition during World War II, was stripped of its last valuables when the interior fittings were sold at auction. The house was demolished and thus what had once been one of Norfolk’s greatest treasures was lost forever.

In 1950, Didlington Hall, broken and neglected after requisition during World War II, was stripped of its last valuables when the interior fittings were sold at auction. The house was demolished and thus what had once been one of Norfolk’s greatest treasures was lost forever.

The murals begin at the entry to the tomb. The perimeter of the arched doorway and wall is painted in a thick stripe of red that doesn’t appear to have faded at all. Against a white background, two human figures are painted on either side of the entryway. The left guardian is a man wearing a black hat holding a staff. The right guardian is a woman holding aloft a feathered fan. Between them centered above the arch is the supernatural bird being Garuda, hovering amongst the clouds, watching over the entryway.

The murals begin at the entry to the tomb. The perimeter of the arched doorway and wall is painted in a thick stripe of red that doesn’t appear to have faded at all. Against a white background, two human figures are painted on either side of the entryway. The left guardian is a man wearing a black hat holding a staff. The right guardian is a woman holding aloft a feathered fan. Between them centered above the arch is the supernatural bird being Garuda, hovering amongst the clouds, watching over the entryway.

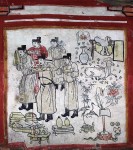

Inside the tomb, the largest mural is on the north wall. It’s a domestic scene depicting the tomb owner’s household. In the background are floor-to-ceiling windows with some excellent roll-up shades, a valance on top and curtains pulled back on the sides. There’s an empty bed in the center, flanked by attendants carrying different vessels and accessories. The stars of the show, however, are a black and white cat in front of the attendants on the left and a black and white dog in front of the attendants on the right. They both have ribbons tied around their necks and the cat is playing with a ball on the end of strip of silk.

Inside the tomb, the largest mural is on the north wall. It’s a domestic scene depicting the tomb owner’s household. In the background are floor-to-ceiling windows with some excellent roll-up shades, a valance on top and curtains pulled back on the sides. There’s an empty bed in the center, flanked by attendants carrying different vessels and accessories. The stars of the show, however, are a black and white cat in front of the attendants on the left and a black and white dog in front of the attendants on the right. They both have ribbons tied around their necks and the cat is playing with a ball on the end of strip of silk.  On the west wall is a dense, dynamic scene of travel through the countryside. An elaborate carriage on the top right of the wall is pulled by Bactrian camel. In the foreground a saddled horse trots, led by a groom. On the top left farmers carry water, plough and hoe their crops. A small figure of horse and rider in the bottom left looks to be transporting goods in packed saddlebags.

On the west wall is a dense, dynamic scene of travel through the countryside. An elaborate carriage on the top right of the wall is pulled by Bactrian camel. In the foreground a saddled horse trots, led by a groom. On the top left farmers carry water, plough and hoe their crops. A small figure of horse and rider in the bottom left looks to be transporting goods in packed saddlebags.  The east wall is a riot of food, drink and animals. Attendants on the left carry trays of food and beverages while on the ground in front of them are pitchers and bamboo steamers doubtless groaning with more of the same. On the top right is a saddle hanging on a rack with a lotus flower fountain to its left. A dear sits in front of the saddle. Other animals in the tableau are a crane, a turtle, and a snake crawling behind an axe on a platform. Between the deer and the crane are bamboo plants. A poem written on a banner to the right of the saddle ties the scene together: “Time tells that bamboo can endure cold weather. Live as long as the spirits of the crane and turtle.”

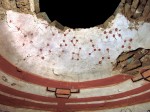

The east wall is a riot of food, drink and animals. Attendants on the left carry trays of food and beverages while on the ground in front of them are pitchers and bamboo steamers doubtless groaning with more of the same. On the top right is a saddle hanging on a rack with a lotus flower fountain to its left. A dear sits in front of the saddle. Other animals in the tableau are a crane, a turtle, and a snake crawling behind an axe on a platform. Between the deer and the crane are bamboo plants. A poem written on a banner to the right of the saddle ties the scene together: “Time tells that bamboo can endure cold weather. Live as long as the spirits of the crane and turtle.”  The ceiling of the tomb is the most damaged — more than half of painting is lost — but vermilion stars connected with lines into constellations are still clearly visible on what remains of it.

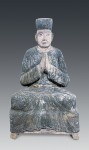

The ceiling of the tomb is the most damaged — more than half of painting is lost — but vermilion stars connected with lines into constellations are still clearly visible on what remains of it. The tomb was looted at some point in the last 1,000 years, but there was one artifact still present: a statue three feet high of a man sitting cross-legged wearing a black robe. Archaeologists believe it’s a representation of the tomb’s occupant. It may even have been a symbolic substitute for his body, a common practice for Buddhist burials at that time.

The tomb was looted at some point in the last 1,000 years, but there was one artifact still present: a statue three feet high of a man sitting cross-legged wearing a black robe. Archaeologists believe it’s a representation of the tomb’s occupant. It may even have been a symbolic substitute for his body, a common practice for Buddhist burials at that time.