When the potato blight first wound its steel skeleton hands around Ireland’s throat in 1845, funds were raised for famine relief not just in the British Empire (Indian donors were particularly forthcoming) but in the United States as well. With its large Irish population, Boston was the epicenter of American efforts driven by the Catholic Church and the local branch of Daniel “The Liberator” O’Connell’s Repeal Association, a political organization dedicated to the repeal of the Act of Union of 1800 which had united the Kingdom of Great Britain with the Kingdom of Ireland. They considered the famine to be a direct result of the union and thus famine relief was very much relevant to their political activism.

When the potato blight first wound its steel skeleton hands around Ireland’s throat in 1845, funds were raised for famine relief not just in the British Empire (Indian donors were particularly forthcoming) but in the United States as well. With its large Irish population, Boston was the epicenter of American efforts driven by the Catholic Church and the local branch of Daniel “The Liberator” O’Connell’s Repeal Association, a political organization dedicated to the repeal of the Act of Union of 1800 which had united the Kingdom of Great Britain with the Kingdom of Ireland. They considered the famine to be a direct result of the union and thus famine relief was very much relevant to their political activism.

Nobody thought it would last, though. Ireland had had potato blights before and while they caused much suffering, they only lasted for one season. Then the blight struck again in 1846, this time hitting harder and earlier. In January of 1847, news reached the US that the blight was destroying another year’s crop and that tens of thousands were dying. Vice President of the United State George Dallas exhorted Washington, D.C. politicians — 33 senators and 11 representatives, including the one from Illinois’ 7th district, Abraham Lincoln, were at the meeting — to raise as much as money as they could in their home states for Irish famine relief.

Boston Mayor Josiah Quincy took the Vice President’s exhortation and ran with it. On February 18th, 1847, he called a meeting of 4,000 of Boston’s richest and most prominent residents. They gathered in Faneuil Hall and were regaled with testimonials on the horrors visited upon the Emerald Isle by the famine. Quincy and other speakers, most notably Harvard President and former US Ambassador to Britain Edward Everett, appealed to the assembly that they do their Christian duty to help the destitute and dying of Ireland. (The religious aspect is significant because this was a heavily Protestant crowd, unlike the first donors to the cause who were Catholic and working class.)

One of the attendants at the Faneuil Hall meeting was Robert Bennet Forbes. Born in Jamaica Plain, now a neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, in 1804, Robert Bennet was the son of Ralph Bennet Forbes and Margaret Perkins Forbes. Both the Perkins and Forbes families were Boston Brahmin, members of the wealthy Protestant upper class of the city. They were merchants by trade and young Robert traveled with his parents from a very young age, crossing the Atlantic for the first time when he was six and experiencing a number of confiscation adventures at the hands of British interference with American ships during the War of 1812. His years of private schooling in France and at the Milton Academy outside Boston came to an end when he was 13 years old. His father’s business failures and ill health spurred the barely teenaged Robert to get a job to help support his parents and seven younger siblings. He went to sea.

One of the attendants at the Faneuil Hall meeting was Robert Bennet Forbes. Born in Jamaica Plain, now a neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, in 1804, Robert Bennet was the son of Ralph Bennet Forbes and Margaret Perkins Forbes. Both the Perkins and Forbes families were Boston Brahmin, members of the wealthy Protestant upper class of the city. They were merchants by trade and young Robert traveled with his parents from a very young age, crossing the Atlantic for the first time when he was six and experiencing a number of confiscation adventures at the hands of British interference with American ships during the War of 1812. His years of private schooling in France and at the Milton Academy outside Boston came to an end when he was 13 years old. His father’s business failures and ill health spurred the barely teenaged Robert to get a job to help support his parents and seven younger siblings. He went to sea.

His maternal uncles James and Thomas Handasyd Perkins owned a company in the Old China Trade selling ginseng, cheese, iron and furs at first before in 1815 specializing in the illegal export of Turkish opium to China. In 1817 little Robert boarded the Canton Packet as a cabin boy, the first of several voyages to Canton and back he made under the command of his uncles. He was a fine sailor and was promoted to officer (third mate) at the age of sixteen. He received his first command of a ship when he was 20 years old and sailed the vessel around the world.

By the time he was 28, Robert Bennet Forbes was rich in his own right, thanks in disturbingly large part to drug trafficking that would have such disastrous consequences for China, and settled down to run the business from Milton, Massachusetts. He became a ship designer, ultimately designing 70 ships. He was also involved in philanthropic works and charitable causes. When Mayor John Quincy appealed for aid at Faneuil Hall, Captain Robert Forbes and his brother John Murray Forbes decided to take immediate action, heading the newly founded New England Committee for the Relief of Ireland and Scotland.

Two days later, the Forbes brothers had come up with a workable plan: to petition Congress to let them use the USS Jamestown, a warship moored in Boston’s Charlestown Navy Yard, to transport desperately needed supplies to Ireland. Forbes volunteered to command the vessel and recruit a crew of volunteers. Because he was an experienced ship’s captain, this offer held weight with his fellow Bostonians on the Committee and with Congress. Two days after that, the New England Committee for the Relief of Ireland and Scotland officially petitioned Congress to grant them use of a warship to deliver relief supplies to famine-stricken Ireland.

On March 3rd, the last day of session, a joint resolution of both Houses was passed authorizing the loan of the frigate Macedonian to Captain George C. DeKay and the Sloop of War Jamestown to Captain Robert Bennet. The resolution stipulated that the President, James K. Polk, and Secretary of the Navy, John Y. Mason, would decided whether the expense of outfitting the ships and their voyages was to be paid for by the government or by the merchants. As the United States was at war with Mexico at that time and money was tight, Mason opted for the latter, lending the ships to the Boston merchants for them to outfit at their expense.

On March 3rd, the last day of session, a joint resolution of both Houses was passed authorizing the loan of the frigate Macedonian to Captain George C. DeKay and the Sloop of War Jamestown to Captain Robert Bennet. The resolution stipulated that the President, James K. Polk, and Secretary of the Navy, John Y. Mason, would decided whether the expense of outfitting the ships and their voyages was to be paid for by the government or by the merchants. As the United States was at war with Mexico at that time and money was tight, Mason opted for the latter, lending the ships to the Boston merchants for them to outfit at their expense.

Congress had never before permitted the use a warship by private parties and it never has since. This remains the only time it has ever happened.

Meanwhile, the Relief Committee got busy raising money and securing supplies.

Over the course of only three weeks, a relief committee chaired by Boston Mayor Josiah Quincy Jr. raised more than $150,000 from donors stretching from Arkansas to Maine. Railroads agreed to ship produce to Boston for free, wharf proprietors donated the use of their docks and newspapers at no charge ran notices from Forbes seeking volunteer crewmembers. The children of Massachusetts donated pennies, churches took up special collections and newly arrived Irish immigrants bore sacks of flour and potatoes to the docks to feed relatives back in their homeland.

The Jamestown was stripped of her armaments and on March 17th, appropriately enough, volunteers from the Laborers Aid Society of Boston began to load the cargo of more than 8,000 barrels of wheat, cornmeal and other non-perishable stores. Bad weather delayed the loading which was completed on March 27th. The next day, the Jamestown set forth for Cork, Ireland, arriving two weeks later on April 12th.

(Random coincidence: the Jamestown had begun its naval duties in 1845 off the coast of West Africa patrolling the sea to suppress the slave trade. Forbes’ uncle Thomas Handasyd Perkins was a slave trader in his younger days when it was still legal. The Jamestown first arrived at the Charlestown Navy Yard in August of 1846 from her first deployment catching slave traders. She was still moored there when the news came of the blight’s persistence.)

In his report on the mission, The Voyage of the Jamestown on Her Errand of Mercy, Captain Forbes noted that when the Jamestown dropped anchor in Cove, a welcoming committee of local citizens greeted the crew with the Cove Temperance Band on hand to play Yankee Doodle over and over. Forbes was invited to receptions and banquets thrown by the (mainly English) authorities both on land and on board the Royal Navy ships that had helped bring the Jamestown in and unload its cargo. Ladies read him poetry. Here’s an apt verse from a poem by a lady known to us today only as Emma:

The “Jamestown” now no ship of war,

Her peaceful way she wends;

A mighty conquest she’s achieved,

And hearts of oak she bends.

The supplies carried by the Jamestown were distributed to more than 150 locations in County Cork. Since heavy bureaucracy was a huge problem with relief supplies then as it is now, the efficient and wide distribution of life-saving food to the starving within 10 days of the ship’s arrival was a notable achievement.

It wasn’t all parties and poems. Here is a passage from Forbes’ report detailing the horrors he witnessed:

It wasn’t all parties and poems. Here is a passage from Forbes’ report detailing the horrors he witnessed:

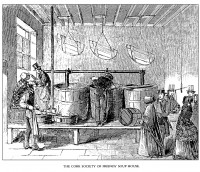

I went with Father Mathew, only a few steps out of one of the principal streets of Cork, into a lane; the valley of the shadow of death was it? alas, no, it was the valley of death and pestilence itself! I saw enough in five minutes, to horrify me — hovels crowded with the sick and dying, without floors, without furniture, and with patches of dirty straw covered with still dirtier shreds and patches of humanity; some called for water to Father Mathew, and others for a dying blessing. From this very small sample of the prevailing destitution we proceeded to a public soup kitchen, under a shed, guarded by police officers, here a large boiler containing rice, meal, &c, was at work, while hundreds of spectres stood without begging for some of this soup, which I can readily conceive would be refused by well bred pigs in this country.

I do not say this with the least disrespect to the benevolent who provide the means and who order the ingredients; the demand, for immediate relief, is so great at Cork, that if the starving can he kept alive, it is all that can be expected; the energies of the poor are so cramped and deadened by want and suffering of every type, that they care only for sustenance, and they are unable to earn it; crowds flock in, from the country to the west and south-west and south-east of Cork, the hospitals and poor houses and jails, are full to overflowing, though numbers die daily to make room for the dying; every corner of the streets is filled with pale care worn creatures, the weak leading and supporting the weaker, women assail you at every turn, with famished babes, imploring alms[.]

Forbes headed back to Boston after 10 days. The Jamestown arrived at Boston Yard on May 17th and Forbes returned it to the Navy. The other warship authorized by the joint resolution, the Macedonian, set out on its relief trip in July. More than 100 civilian relief ships also did their bit that year, bringing food and cash donations from all over the United States to Ireland. The Great Hunger spurred America’s first major disaster relief effort, and indeed the first global disaster relief effort.

While he was outfitting the ship, Forbes received a letter from his friend and Unitarian pastor Reverend R.C. Waterson pointing out that in 1676, Ireland had sent donations to help relieve the suffering of the Plymouth colonists during King Philip’s War. It doesn’t get much attention today, but King Philip’s War was an unmitigated disaster for the New England colonies leaving their population literally decimated, a dozen towns destroyed, half of all the towns attacked and their economy in tatters. (It was a disaster for the Native Americans too. The Wampanoags and Narragansetts were all but destroyed.) Forbes calculated that adjusted for inflation, the 1676 Irish donations would amount to $200,000 in his day ($1,450,000 in ours).

While he was outfitting the ship, Forbes received a letter from his friend and Unitarian pastor Reverend R.C. Waterson pointing out that in 1676, Ireland had sent donations to help relieve the suffering of the Plymouth colonists during King Philip’s War. It doesn’t get much attention today, but King Philip’s War was an unmitigated disaster for the New England colonies leaving their population literally decimated, a dozen towns destroyed, half of all the towns attacked and their economy in tatters. (It was a disaster for the Native Americans too. The Wampanoags and Narragansetts were all but destroyed.) Forbes calculated that adjusted for inflation, the 1676 Irish donations would amount to $200,000 in his day ($1,450,000 in ours).

“It is an interesting fact, that the people of Ireland nearly two hundred years ago, thus sent relief to our ‘Pilgrim Fathers,’ in the time of their need, and that what we have been doing for that famishing country is but a return for what their fathers did for our fathers, and the whole circumstance proves a verification of the scripture, ‘Cast thy bread upon the waters, for thou shalt find it after many days.’

I cannot but think that this fact will be of interest in the pamphlet which you intend to publish. I consider the mission of the Jamestown as one of the grandest events in the history of our country. A ship of war changed into an angel of mercy, departing on no errand of death, but with the bread of life to an unfortunate and perishing people.”