The earliest known draft of the King James Bible (KJB) has been discovered in the archives of Cambridge University’s Sidney Sussex College. Montclair University English professor Jeffrey Alan Millar found the translation of parts of the Apocrypha in a notebook kept by Samuel Ward, Puritan minister, Fellow of Cambridge’s newly founded Sidney Sussex College and one of 47 scholars appointed to correct errors in past translations and make a new authorized version of the Bible in English. The notebook had been inventoried before, but its contents were identified as biblical commentary, not as work product of the translation of the King James Bible.

The earliest known draft of the King James Bible (KJB) has been discovered in the archives of Cambridge University’s Sidney Sussex College. Montclair University English professor Jeffrey Alan Millar found the translation of parts of the Apocrypha in a notebook kept by Samuel Ward, Puritan minister, Fellow of Cambridge’s newly founded Sidney Sussex College and one of 47 scholars appointed to correct errors in past translations and make a new authorized version of the Bible in English. The notebook had been inventoried before, but its contents were identified as biblical commentary, not as work product of the translation of the King James Bible.

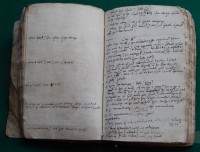

The translators were grouped into six committees, two companies from Oxford, two from Cambridge and two from Westminster, each assigned different sections of the Bible to translate. Ward was part of the Second Cambridge Company charged with translating the Apocrypha. He and his colleagues were set to the task in 1604 and in 1608, they were the first company to complete their work. The notebook covers this entire period, 1604 to 1608, and is written in Ward’s own hand, the only known draft of the KJB written by an identifiable translator.

In fact, other extant drafts aren’t really what we think of as drafts. The translators had a strict brief: they were to work off the previous authorized version, the Bishop’s Bible, and only correct areas where the translation was problematic. Thus previously known “drafts” are in the form of notes on the pages of the Bishop’s Bible (King James had an unbound version distributed to all the translators for this purpose), a handwritten copy of the completed translation of the New Testament Epistles and two handwritten copies of notes taken during a discussion by the committee reviewing the full translation just before publication.

In fact, other extant drafts aren’t really what we think of as drafts. The translators had a strict brief: they were to work off the previous authorized version, the Bishop’s Bible, and only correct areas where the translation was problematic. Thus previously known “drafts” are in the form of notes on the pages of the Bishop’s Bible (King James had an unbound version distributed to all the translators for this purpose), a handwritten copy of the completed translation of the New Testament Epistles and two handwritten copies of notes taken during a discussion by the committee reviewing the full translation just before publication.

None of those are known to have been written by the translators nor do they document the actual hard work of translation coming as they do at the end of the process. Ward’s notebook is therefore the only extant document to give scholars a view of the day-to-day work of a KJB translator.

In two different places in the notebook, there appears what seems to be nothing but a sequence of running notes on the Bishops’ Bible’s translation of two different Apocryphal books. The longer of the two sequences – occupying sixty-six pages of the notebook in total – covers all nine chapters, from the first verse to the last, of the book known as 1 Esdras or 3 Ezra, positioned first in the KJB among the Apocrypha. The shorter sequence, on the other hand, spans just chapters three and four of the Apocryphal book Wisdom. In each case, the notes typically take a similar form. A verse number is given, followed by a quotation from the Bishops’ Bible’s translation, often only a word or phrase. This Ward encloses in a single bracket, and then proceeds to provide an alternative English translation, usually juxtaposing it with the corresponding portion of the verse in Greek, the language in which the vast majority of the Apocryphal books were known to survive at the time. For instance, a note in Ward’s draft for 1 Esdras 1:2 reads simply, “he set] having sett” (sic), followed by a transcription of the Greek word from 1 Esdras in question. The entry represents Ward’s suggestion that the Greek word translated as “he set” in the Bishops’ Bible should instead be translated as “having set”. On turning to the KJB as it appeared in 1611, we find that this is exactly what was done.

Ward’s notes clearly show him tackling the translation on his own, not taking notes on the work of his company. Before this discovery, it was generally believed that the committee members worked together as a team on their appointed sections of the Bible. That may still be the case with the other five companies, but the notebook indicates the members of the Second Cambridge Company at least did some individual work. Several of Ward’s proposed translations did not make it into the final KJB and there are sections where he makes changes on what seems to be the input of others, so there was likely interplay between company members before the final draft was submitted by the group.

To what extent this complex (if also precarious) interplay between individual and group translation evidently at work in the Apocrypha company points to the possibility of a similar dynamic at work across the Bible’s five other translation companies is hard to say. In the end, though, an awareness of that difficulty itself may represent one of the most valuable insights offered by Ward’s draft. Not only does it profoundly complicate the notion that members of a given company necessarily worked on the translation of each book together as a team; it forces us to think harder about the extent to which all the companies necessarily set about their work in the same or even a similar way. The KJB, in short, may be far more a patchwork of individual translations – the product of individual translators and individual companies working in individual ways – than has ever been properly recognized.

Samuel Ward’s work on the King James Bible assured his career. In 1610 he was appointed Master of Sidney Sussex College. The next year he became chaplain to King James I. In 1615 he was made Archdeacon of Taunton and prebendary of Wells Cathedral. In 1618 he was appointed prebendary of York too and less than a year later he was selected to be one of the English delegates to the Synod of Dort where his scholarship so impressed Dutch theologian Simon Episcopius that he declared Ward to be the most learned member of the synod.

Samuel Ward’s work on the King James Bible assured his career. In 1610 he was appointed Master of Sidney Sussex College. The next year he became chaplain to King James I. In 1615 he was made Archdeacon of Taunton and prebendary of Wells Cathedral. In 1618 he was appointed prebendary of York too and less than a year later he was selected to be one of the English delegates to the Synod of Dort where his scholarship so impressed Dutch theologian Simon Episcopius that he declared Ward to be the most learned member of the synod.

The train of lucrative livings and academic successes only derailed at the very end of his life thanks to the English Civil War. In 1643, governments of Scotland and England approved the Solemn League and Covenant, a treaty between the Scottish Covenanters and English Parliamentarians in which the latter agreed to integrate the Scottish presbyterian system into the Church of England in exchange for military aid. With terms like “we shall in like manner, without respect of persons, endeavour the extirpation of Popery, Prelacy, (that is, church-government by Archbishops, Bishops, their Chancellors, and Commissaries, Deans, Deans and Chapters, Archdeacons, and all other ecclesiastical Officers depending on that hierarchy,)” the Covenant did not appeal to Ward. He and other clerics who refused to take the Covenant were imprisoned in St. John’s College. Ward’s health declined precipitously and he was allowed to return to his home at Sidney Sussex where he was still Master. On August 30th, 1643, he took ill in chapel. Eight days later, he died in his bed at 71 years old.