The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston has opened the first monographic exhibition in the United States of the works of Carlo Crivelli, a Venetian artist of the 15th century whose genius has been unjustly neglected, overshadowed by his more famous (and more Florentine) contemporaries.

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston has opened the first monographic exhibition in the United States of the works of Carlo Crivelli, a Venetian artist of the 15th century whose genius has been unjustly neglected, overshadowed by his more famous (and more Florentine) contemporaries.

Born in Venice to a family of painters in around 1430-35, Carlo Crivelli’s first appears in the historical record in 1457, and he was already an independent master by then and therefore at least 25 years old. The record in question documents the scandal that drove Carlo out of Venice. On March 7th, 1457, the prosecutor asked the Council of Forty, the Republic of Venice’s version of the Supreme Court, to pass sentence on Carlo Crivelli for adultery. Apparently he was having an affair with Tarsia, wife of a sailor named Francesco Cortese. He had spirited her away from Francesco’s brother’s house and for months had “carnal knowledge of her in contempt of God and holy matrimony.” Carlo was sentenced to six months in prison and a fine of 200 lire. That was actually a relatively light sentence for the time.

After he served his time, Carlo went to Padua where he worked in Francesco Squarcione’s studio. Squarcione was the first artist to market himself as a teacher of the new Renaissance style, imparting lessons in linear perspective and assiduously collecting antiquities to give his students classical models to copy. Andrea Mantegna had apprenticed under Squarcione in the 1440s, and the master’s obsession with Roman antiquity was thoroughly inculcated into the pupil. Mantegna and Crivelli share an intense attention to architectural detail, the use of forced perspective and a bold, black outline that gives forms a chiseled sharpness. Crivelli may even have studied under Mantegna briefly.

After he served his time, Carlo went to Padua where he worked in Francesco Squarcione’s studio. Squarcione was the first artist to market himself as a teacher of the new Renaissance style, imparting lessons in linear perspective and assiduously collecting antiquities to give his students classical models to copy. Andrea Mantegna had apprenticed under Squarcione in the 1440s, and the master’s obsession with Roman antiquity was thoroughly inculcated into the pupil. Mantegna and Crivelli share an intense attention to architectural detail, the use of forced perspective and a bold, black outline that gives forms a chiseled sharpness. Crivelli may even have studied under Mantegna briefly.

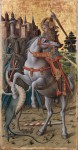

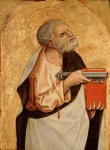

Crivelli spent a few years in Dalmatia with Giorgio Schiavone, aka Juraj Ćulinović, who he likely met in Padua through Squarcione. By 1468, he was in Le Marche, a region of central Italy on the Adriatic coast, where he would remain until his death in around 1494. Most of his surviving works and all of the ones he explicitly dated were painted during his years in Le Marche. He received prestigious commissions for religious works, primarily altarpieces, the largest and most elaborate of which were the monumental high altarpieces for the cathedrals of Ascoli Piceno and Camerino. The pieces on display at the Gardner were on the main not composed as individual works but rather as sections of altarpieces that at some point were sawn apart and sold separately to collections and museums in Europe and the United States. Isabella Stewart Gardner brought the first Crivelli painting to the United States when she bought Saint George Slaying the Dragon in 1897.

Crivelli spent a few years in Dalmatia with Giorgio Schiavone, aka Juraj Ćulinović, who he likely met in Padua through Squarcione. By 1468, he was in Le Marche, a region of central Italy on the Adriatic coast, where he would remain until his death in around 1494. Most of his surviving works and all of the ones he explicitly dated were painted during his years in Le Marche. He received prestigious commissions for religious works, primarily altarpieces, the largest and most elaborate of which were the monumental high altarpieces for the cathedrals of Ascoli Piceno and Camerino. The pieces on display at the Gardner were on the main not composed as individual works but rather as sections of altarpieces that at some point were sawn apart and sold separately to collections and museums in Europe and the United States. Isabella Stewart Gardner brought the first Crivelli painting to the United States when she bought Saint George Slaying the Dragon in 1897.

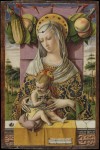

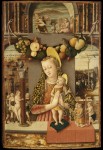

At a time when leading painters in Florence were espousing naturalism, Crivelli embraced the elongated figures, rich colors and ornate gold backgrounds of the International Gothic style of the century before his. To that he added a detailed realism, painstakingly rendering every textile, brick and hair to a degree unmatched by any one of his Italian peers. To create the illusion of depth, dimension and texture, he took trompe l’oeil to new heights by creating gemstones, the ornamental features of armor, brocades and silks, even tears, in gesso, and then covering them with paint and gold leaf. He added more decorative details to gilded areas with a punch or stylus, given them palpable texture. He combined still life with the garlands of ancient sarcophaguses and created a swag of ripe, luscious, oversized fruits or placed individual pieces — his signature cucumber crops up practically everywhere — in panel after panel. It’s like the Byzantine icon and Northern European realism and Italian Renaissance illusionism had a beautiful baby.

At a time when leading painters in Florence were espousing naturalism, Crivelli embraced the elongated figures, rich colors and ornate gold backgrounds of the International Gothic style of the century before his. To that he added a detailed realism, painstakingly rendering every textile, brick and hair to a degree unmatched by any one of his Italian peers. To create the illusion of depth, dimension and texture, he took trompe l’oeil to new heights by creating gemstones, the ornamental features of armor, brocades and silks, even tears, in gesso, and then covering them with paint and gold leaf. He added more decorative details to gilded areas with a punch or stylus, given them palpable texture. He combined still life with the garlands of ancient sarcophaguses and created a swag of ripe, luscious, oversized fruits or placed individual pieces — his signature cucumber crops up practically everywhere — in panel after panel. It’s like the Byzantine icon and Northern European realism and Italian Renaissance illusionism had a beautiful baby.

While he was highly esteemed during his lifetime — he was knighted for his artistic contributions — Carlo Crivelli was forgotten all too soon. Florence-centric Vasari didn’t include him in his seminal biography of the artists and he was consistently overlooked until the 19th century when the Pre-Raphaelites rediscovered him. Revival or no, mainstream critics still pooh-poohed Crivelli as a throwback of sorts, too enamoured of the old-fashioned medieval style to be worth emulating. This is from an 1863 article about the “London Art Scene” in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine:

While he was highly esteemed during his lifetime — he was knighted for his artistic contributions — Carlo Crivelli was forgotten all too soon. Florence-centric Vasari didn’t include him in his seminal biography of the artists and he was consistently overlooked until the 19th century when the Pre-Raphaelites rediscovered him. Revival or no, mainstream critics still pooh-poohed Crivelli as a throwback of sorts, too enamoured of the old-fashioned medieval style to be worth emulating. This is from an 1863 article about the “London Art Scene” in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine:

Its manner is severe, hard, quaint, and even fantastic. It is remarkable for elaboration of detail. And as a further characteristic of the school, or rather of the individual master, should be observed the introduction of gold not only in the background, but extending even to the gilding of the dress and the illumination of the hair. Making allowance for the period when painted, this is truly a glorious work ; but to revive this obsolete style, as attempted in Germany and England, except, perhaps, for strict architectural decoration, were certainly a monstrous mistake, of which we imagine our artists are by this time thoroughly convinced.

Even today when such judgments on ideal artistic progression are as passé as the above author held Crivelli’s work to be, he still flies under the radar, which is why it has taken until now for a US museum to dedicate a whole show just to him. Loans from major museums in Europe and the United States have allowed the Gardner to bring together 23 of his paintings and the only drawing known to have survived. Four of the six panels from the Porto San Giorgio altarpiece, one of which is the Gardner’s Saint George, have been reunited in the show.

Even today when such judgments on ideal artistic progression are as passé as the above author held Crivelli’s work to be, he still flies under the radar, which is why it has taken until now for a US museum to dedicate a whole show just to him. Loans from major museums in Europe and the United States have allowed the Gardner to bring together 23 of his paintings and the only drawing known to have survived. Four of the six panels from the Porto San Giorgio altarpiece, one of which is the Gardner’s Saint George, have been reunited in the show.

Ornament and Illusion: Carlo Crivelli of Venice runs through January 26th, 2016. To find out more about the artist, you must visit the Gardner’s excellent website dedicated to the exhibition and Crivelli’s work. There is video and audio about the conservation of Saint George, a slider showing those bold, black lines in the underdrawing, a digital reassembling of the altarpiece of Porto San Giorgio, detailed views of those amazing 3D textures he achieved with gesso and much more.

Ornament and Illusion: Carlo Crivelli of Venice runs through January 26th, 2016. To find out more about the artist, you must visit the Gardner’s excellent website dedicated to the exhibition and Crivelli’s work. There is video and audio about the conservation of Saint George, a slider showing those bold, black lines in the underdrawing, a digital reassembling of the altarpiece of Porto San Giorgio, detailed views of those amazing 3D textures he achieved with gesso and much more.