Otzi the Iceman, the exceptionally well-preserved 5,300-year-old mummy discovered by hikers in the Otzal Alps on September 19th, 1991, is officially the world’s oldest known tattooed person. You might have assumed that to be the case considering he died around 3,250 B.C., but there was another candidate for the title: a South America mummy of the Chinchorro culture believed to have died around 4,000 B.C. who has a line of dots on his upper lip forming a pointillist mustache.

Otzi the Iceman, the exceptionally well-preserved 5,300-year-old mummy discovered by hikers in the Otzal Alps on September 19th, 1991, is officially the world’s oldest known tattooed person. You might have assumed that to be the case considering he died around 3,250 B.C., but there was another candidate for the title: a South America mummy of the Chinchorro culture believed to have died around 4,000 B.C. who has a line of dots on his upper lip forming a pointillist mustache.

The Chinchorro people lived along the Pacific coast of what is today Chile and south Peru between 7,000 and 1,100 B.C. Chinchorro mummies, both natural and deliberate, have been found from early in the date range. They are the oldest known human mummies but only one of them is known to have a tattoo. The mummy with the mustache tattoo was discovered in the bluffs of El Morro overlooking the city of Arica, Chile, in 1983. It’s a male who was around 35–40 years old when he died. Radiocarbon testing of a sample of lung tissue in the 1980s returned a date of 3,830 years BP (before the present).

So according to the radiocarbon dating, Otzi is significantly older than the Chinchorro mummy, but a simple mistake in the scholarship misread 3,830 BP as 3,830 B.C. and the error was unwittingly picked up and repeated by subsequent researchers. The new erroneous date was then transposed to 5,780 BP, which in turn was mistakenly read as 5,780 B.C. in a later study. And thus a simple reading error was compounded over 20 years of scholarship to add 4,000 years to the Chinchorro mummy’s age.

So according to the radiocarbon dating, Otzi is significantly older than the Chinchorro mummy, but a simple mistake in the scholarship misread 3,830 BP as 3,830 B.C. and the error was unwittingly picked up and repeated by subsequent researchers. The new erroneous date was then transposed to 5,780 BP, which in turn was mistakenly read as 5,780 B.C. in a later study. And thus a simple reading error was compounded over 20 years of scholarship to add 4,000 years to the Chinchorro mummy’s age.

Now that this error has been spotted and corrected, Otzi’s tattoos are confirmed to be the oldest known. As an aside, the Princess of Ukok who is famed for her intricate, highly artistic tattoos of fantastical animals and dates to 400–200 B.C., is 13th (or so, there are three other Pazyryk culture tattooed mummies from the same date range) on the list of oldest known tattoos.

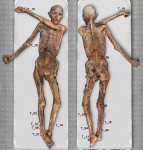

Otzi’s tats are nothing like the Princess of Ukok’s. They are simple in design — groupings of parallel lines and crosses — and were not decorative. There are 61 lines and crosses tattooed on his body, the last of them discovered recently almost 25 years after the Iceman’s body was found. The tattoo was hidden in the darkened skin of his ribcage and was only identified thanks to a new study that used multispectral photographic imaging techniques to scan his entire body in a range of light from IR to UV.

Otzi’s tats are nothing like the Princess of Ukok’s. They are simple in design — groupings of parallel lines and crosses — and were not decorative. There are 61 lines and crosses tattooed on his body, the last of them discovered recently almost 25 years after the Iceman’s body was found. The tattoo was hidden in the darkened skin of his ribcage and was only identified thanks to a new study that used multispectral photographic imaging techniques to scan his entire body in a range of light from IR to UV.

Most of the tattoos are in areas that radiological studies confirm must have been painful due to degeneration and chronic illness, which indicates they had a therapeutic purpose rather than a symbolic one. The ribcage tattoo isn’t on a worn joint, his legs or his spine like the others, but Otzi suffered from several afflictions that could cause chest pain — gallbladder stones, whipworms, atherosclerosis — so it too could have been intended to alleviate pain.

The tattoos were made by cutting fine lines into the epidermis and then rubbing charcoal dust into the cuts. Since almost all of the tattoos are on acupuncture points, researchers believe the cutting may have been an early form of acupuncture which first appears on the historical and archaeological record in China around 100 B.C. but documenting what was already an established practice by then.

The tattoos were made by cutting fine lines into the epidermis and then rubbing charcoal dust into the cuts. Since almost all of the tattoos are on acupuncture points, researchers believe the cutting may have been an early form of acupuncture which first appears on the historical and archaeological record in China around 100 B.C. but documenting what was already an established practice by then.

Although Ötzi is the oldest tattooed human, the paper’s authors conclude this will likely change: Ötzi’s tattoos are indicative of social and/or therapeutic practices that predate him, and future archaeological finds and new techniques should someday lead to even older evidence of tattooed mummies.

“Apart from the historical implications of our paper, we shouldn’t forget the cultural roles tattoos have played over millennia,” [study co-author Lars] Krutak says. “Cosmetic tattoos — like those of the Chinchorro mummy — and therapeutic tattoos — like those of the Iceman — have been around for a very long time. This demonstrates to me that the desire to adorn and heal the body with tattoo is a very ancient part of our human past and culture.”