A unique opportunity to excavate an undeveloped field on Norway’s Ørland peninsula has revealed the remains of a large and wealthy Iron Age settlement. The site is adjacent to Norway’s Main Air Station which is expanding to make room for 52 new F-35 fighter jets the government recently purchased. By Norwegian law, the property must be surveyed by archaeologists before construction begins, and because this site is so extensive (91,000 meters squared or more than 22 acres), the survey is a major project with more than 20 staff working for 40 weeks at a cost of 41 million Norwegian Krone ($4,700,000), not counting the additional costs for room and board and large excavators.

A unique opportunity to excavate an undeveloped field on Norway’s Ørland peninsula has revealed the remains of a large and wealthy Iron Age settlement. The site is adjacent to Norway’s Main Air Station which is expanding to make room for 52 new F-35 fighter jets the government recently purchased. By Norwegian law, the property must be surveyed by archaeologists before construction begins, and because this site is so extensive (91,000 meters squared or more than 22 acres), the survey is a major project with more than 20 staff working for 40 weeks at a cost of 41 million Norwegian Krone ($4,700,000), not counting the additional costs for room and board and large excavators.

The excavators are necessary to strip a very thin layer of topsoil which has been churned up by farming. The land has been farmed for centuries, going at least as far back 1,500 years ago when it was right on the bay. Now it’s a mile inland. Its former position on the coast made it an important location for Iron Age Norwegians.

The excavators are necessary to strip a very thin layer of topsoil which has been churned up by farming. The land has been farmed for centuries, going at least as far back 1,500 years ago when it was right on the bay. Now it’s a mile inland. Its former position on the coast made it an important location for Iron Age Norwegians.

“This was a very strategic place,” says Ingrid Ystgaard, project manager at the Department of Archaeology and Cultural History at NTNU University Museum. “It was a sheltered area along the Norwegian coastal route from southern Norway to the northern coasts. And it was at the mouth of Trondheim Fjord, which was a vital link to Sweden and the inner regions of mid-Norway.”

Excavations have already confirmed that the people who lived there were prosperous, as testified to by the quality of their garbage. Archaeologists were delighted to find middens — ancient garbage pits — on the site, because they rarely survive so long in the acidic soil of Norway. Thanks to its coastal history, the site’s soil is composed of alkaline ground-up seashells which has allowed delicate organic remains like animal and fish bones to survive to this day.

Excavations have already confirmed that the people who lived there were prosperous, as testified to by the quality of their garbage. Archaeologists were delighted to find middens — ancient garbage pits — on the site, because they rarely survive so long in the acidic soil of Norway. Thanks to its coastal history, the site’s soil is composed of alkaline ground-up seashells which has allowed delicate organic remains like animal and fish bones to survive to this day.

“Nothing like this has been examined anywhere in Norway before,” Ystgaard said.

There are enough bones to figure out what kinds of animals they came from, and how the actual animal varieties relate to today’s wild and domesticated animals, she said. The archaeologists have also found fish remains, from both salmon and cod, and the bones from seabirds, too.

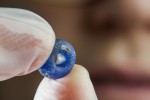

These finds will give archaeologists a unique glimpse into the daily lives and diets of the Iron Age residents. Other artifacts found in the middens include a blue glass bead, several amber beads and a shard from a green drinking beaker that was imported from the Rhine Valley. These are expensive pieces, a testament to the wealth of a settlement that could afford to trade for such high-end goods.

These finds will give archaeologists a unique glimpse into the daily lives and diets of the Iron Age residents. Other artifacts found in the middens include a blue glass bead, several amber beads and a shard from a green drinking beaker that was imported from the Rhine Valley. These are expensive pieces, a testament to the wealth of a settlement that could afford to trade for such high-end goods.

The precision work of the excavators has peeled back the top layers of soil a centimeter at a time revealing discolorations and holes in the soil that are basically a blueprint of the structures in the settlement.

So far, these marks in the soil show that there were three buildings arranged in the shape of a U. The two longhouses that were parallel to each other measured 40 metres and 30 metres and were connected by a smaller building.

The 40-metre longhouse contained several fire pits, at least one of which was clearly used for cooking. Other fire pits may have provided light for handwork, or for keeping the longhouse warm.

Ystgaard believes there are probably more archaeological remains outside the 22 acres available to them to survey, perhaps a burial ground and harbour with the remains of boat houses, but they have more than enough meaty material to sink their teeth into on the airbase site. The opportunity to explore how the Iron Age site was laid out — where the houses were, where the fireplaces were, where the garbage pits were — is precious and rare and they intend to take full advantage of it.

Ystgaard believes there are probably more archaeological remains outside the 22 acres available to them to survey, perhaps a burial ground and harbour with the remains of boat houses, but they have more than enough meaty material to sink their teeth into on the airbase site. The opportunity to explore how the Iron Age site was laid out — where the houses were, where the fireplaces were, where the garbage pits were — is precious and rare and they intend to take full advantage of it.