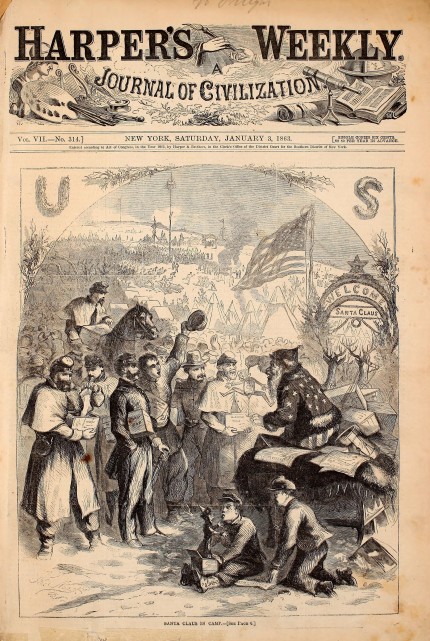

The great 19th century political cartoonist Thomas Nast is widely credited with having created the look of Santa Claus as we know him today. Inspired by Clement Moore’s description of the “jolly old elf” in his 1823 poem A Visit from St. Nicholas, aka The Night Before Christmas, Nast first depicted Santa in the January 3, 1863, issue of Harper’s Weekly. On the cover was a scene captioned “Santa Claus in Camp” in which Saint Nick brings toys and good cheer to Union soldiers. It seems that Santa, much like Nast himself who was a staunch Republican and abolitionist, had picked a side in the Civil War, and he wasn’t at all subtle about it.

Santa’s blue (of course) coat has white stars on it and his pants have red and white stripes, similar to garb donned by other patriotic icons drawn by Nast like Columbia and Uncle Sam. He has delivered parcels to the soldiers. One finds a sock inside, doubtless a welcome gift in the bleak midwinter after the devastating loss at Fredericksburg which saw more than 12,000 of his comrades killed, wounded or taken captive. A drummer boy in the foreground stares with wide-eyed surprise at the jack-in-the-box that leapt out of his present.

But it’s the toy Santa is holding that is most remarkable. Here’s Harper’s explanation of it:

Santa Claus is entertaining the soldiers by showing them Jeff Davis’ future. He is tying a cord pretty tightly round his neck, and Jeff seems to be kicking very much at such a fate.

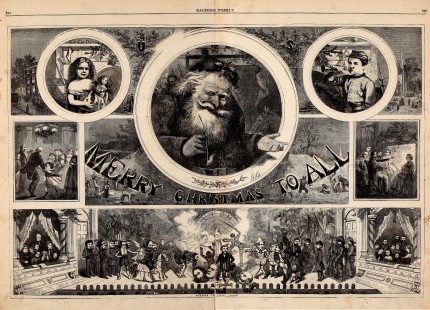

Inside the same issue was a more sentimental approach to enlisting Santa in the Union cause. Nast’s two-page cartoon entitled “Christmas Eve” frames two Christmas scenes: a mother looking out the window praying while her two children sleep, and a lonely soldier by a campfire, presumably her husband, looking at a picture of his wife and children. Below them are vignettes of war and fresh graves. Above them Santa Claus brings consolation in the form of presents to the family home and to the front.

By Christmas of 1865, Santa’s wartime support of the Union had softened from stringing up effigy Jefferson Davis with his own hands to presiding over a Christmas pageant starring Ulysses S. Grant as the giant killer from Jack and the Beanstalk. Sure, the decapitated heads of Confederate generals Robert E. Lee, John Bell Hood and Richard Ewell are at Grant’s feet, but it’s just metaphoric playacting and anyway Santa’s involvement is restricted to a wink and an avuncular smile, possibly a touch on the gloating side.

After the war, Nast continued to draw Santa Claus for seasonal issues of the magazine. It was Thomas Nast who introduced the idea that Santa Claus has a toy workshop in the North Pole, although in his vision Santa did all his own labour. “Santa Claus and His Works” was printed in the December 29, 1866, issue of Harper’s. Santa’s address is noted in the border encircling the central vignettes as “Santa Claussville, N.P.” His January 1, 1881, panel of Santa Claus was hugely popular and endlessly reproduced. It became the predominant view of Santa Claus until Coca-Cola commissioned Haddon Sundblom to make them a jolly soda-shilling Santa in 1931.

After the war, Nast continued to draw Santa Claus for seasonal issues of the magazine. It was Thomas Nast who introduced the idea that Santa Claus has a toy workshop in the North Pole, although in his vision Santa did all his own labour. “Santa Claus and His Works” was printed in the December 29, 1866, issue of Harper’s. Santa’s address is noted in the border encircling the central vignettes as “Santa Claussville, N.P.” His January 1, 1881, panel of Santa Claus was hugely popular and endlessly reproduced. It became the predominant view of Santa Claus until Coca-Cola commissioned Haddon Sundblom to make them a jolly soda-shilling Santa in 1931.

Suffering from financial troubles, in 1889 Nast published a collection of his Santa cartoons from Harper’s Weekly in a book called Christmas Drawings for the Human Race because “they appeal to the sympathy of no particular religious denomination or political party, but to the universal delight in the happiest of holidays, consecrated by the loftiest associations and endeared by the tenderest domestic traditions.” Santa hanging puppet Jeff Davis is in there, but the overwhelming majority of the drawings are tender post-war confections of children (his own kids were his models) and toys and sleighs on roofs. The day of the partisan Santa was over.

Suffering from financial troubles, in 1889 Nast published a collection of his Santa cartoons from Harper’s Weekly in a book called Christmas Drawings for the Human Race because “they appeal to the sympathy of no particular religious denomination or political party, but to the universal delight in the happiest of holidays, consecrated by the loftiest associations and endeared by the tenderest domestic traditions.” Santa hanging puppet Jeff Davis is in there, but the overwhelming majority of the drawings are tender post-war confections of children (his own kids were his models) and toys and sleighs on roofs. The day of the partisan Santa was over.